Ethical Space of Engagement

The ESE as guidance to performing an ethical space of engagement

Let me begin with the phenomena of third space, itself, and how it allowed me to reconsider my positionality within the BearWatch project, in a way that it dislodged me from the paralyzing fear of drafting a proposal that was either extractive or dis-engaged. Grasping the possible existence of a third space in-between requires, as explained in the previous round, thinking about difference without falling into the trap of binary, essentialist approaches similar to those that position western and Indigenous knowledges against each other in a false dichotomy (see Agrawal, 2002). To engage this concept of in-betweenness in a meaningful way, is thus by necessity a philosophical endeavour that leads us away from the ontological certainties provided by Cartesian divides towards the possibilities of uncertainty. In-betweenness allows for intra-relational thinking across entities and events, rather than inter-relational thinking merely between entities and events. By extent it challenges the persistent split between nature and culture or knowing and being in hegemonic western sciences.

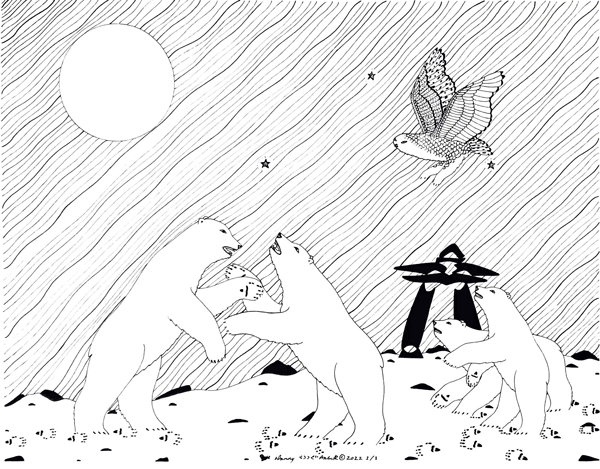

Figure 5: The Ethical Space Diagram, as published by the IISAAK OLAM foundation (2019)

What the concept of an in-between did for me specifically at the start of my research was to help me move away from thinking about immersed engagement/appropriation on the one hand, and respectful distance/erasure on the other hand as somehow closed, mutually exclusive categories. It allowed me to consider my research as practiced within an ever unfolding space of tension: as an ongoing correspondence in-between practices of immersed engagement and practices of considerate incommensurability- but never as fully innocent. Eventually I realized that there would be no project or approach that I could take, which would not render me already implicated in the relational webs of ongoing settler-colonialism in Canada. Being a white settler-guest conducting PhD research in Canada would have me consider the exact same deliberations I was working through in Bearwatch over and over again, regardless of which project I would join. These realizations eventually helped me decide to embrace my position, as embedded within-, but not resonant to all interests of the Bearwatch project. They allowed me to formulate a ‘non-innocent’ approach (see Haraway, 1988) towards the complex challenges that I aimed to address. Non-innocent approaches are approaches that recognize oneself as implicated and invested - not distanced and des-invested. Embracing a non-innocent approach helped me decide to stay on the project, while understanding such an approach would require both resonant and dissonant intra-actions with other material agencies of the project. As such I started navigating and negotiating with my supervisors and the project PI’s, to variously practice immersed engagement, respectful distance through an ethics of ‘incommensurability’ and, importantly, where necessary ‘refusal’, as conditions to my research practices within the overarching BearWatch project. Such an understanding of the ESE, as a space that allows for a practice of negotiated navigation, also clarifies what it is not. The ESE is not merely an intellectual exercise. Purely theoretical or philosophical endeavours involving Indigenous people, their knowledge and their models without accompanied (ethical) practice, mostly serve introspective institutionalized, western knowledge production and the careers of non-Indigenous researchers. There is no reaching across in such endeavours, and therefore they do not configure an ethical space of engagement. The ethical-, in-between-, or third space is not merely an idea, it is an active practice-philosophy, guided by Indigenous principles, and intra-actively co-constituted in-between cultures. It needs to be practiced. and it needs to be practiced together with, in my particular case, Inuit partners. I managed to detach myself from short term, data-driven research in direct service of BearWatch genetic science towards prioritizing research that, guided by the principles of the ethical space of engagement, explores the im/possibilities of material, contextual, and ethical (re)configurations within the relational entanglements of Nunavut-based fieldwork of the BearWatch project. This repositioning moved me in definitive ways away from more metaphorical explorations around knowledge conciliation, into the material environments of the Kitikmeot and Kivalliq regions of Inuit Nunangat. This physical repositioning is of course only one of multiple processes that were set in motion by seriously engaging with the concept of a third space. Although no longer confined to the boundaries of narrow disciplinary expectations and data-specific interests of Bearwatch, my work remains deeply entangled with other material and agential elements of the project apparatus- or arguably even more so. For example with the overarching apparatus of Nunavut based science-driven polar bear management, the material apparatus of institutionalized eurocentric sciences, and most of all the entanglements of day-to-day priorities of our research partners in collaborating Inuit communities. Although the fieldwork of projects like BearWatch are often considered-, and presented- to evolve predominantly around land-based surveys and sample collection, most time and resources are spent on preparatory and circumstantial activities- happening in the day-to-day relational configurations between researchers and community members in the hamlets. It was my participation, during initial visits, in such day-to-day community-based activities that provided me with the biggest opportunities to build relationships and learn about the realities of Arctic-based everyday life. And it were these experiences that helped me decide on a creative-practice approach like aesthetic action, that would allow for such daily practices to be included in my research. Such a focus on practice, however, also implies the importance of taking a closer look at the principles and conditions with which the ESE proposes to ethically guide such practices.

The ESE as guiding principles for ethical practice.

To design a practice-based methodology that respects the conditions and guiding principles offered by the conceptualization of an ethical space, I have based myself on a close reading of Ermine’s writing on the ESE (2007), and that of literature on the 1613 Two-Row-Wampum treaty between the Dutch and the Haudenosaunee- understood to draw from similar principles. From this reading I understand at least two important guiding principles to emerge from the ESE. The first principle is a willingness to engage, and the second one is a principle of respecting boundaries. Let’s start with the willingness to ‘engage outside of the cages of one’s usual cultural and institutional allegiances’ (Ermine, 2007). Such an engagement outside of ‘one’s usual cultural and institutional allegiances’ (Ermine, 2007), goes against some readings of the 1613 Two-Row-Wampum treaty to prescribe a form of mutual isolation (see for example Cairns, 2000; Usher, 2000). Such readings are not only contradicted by Ermine, but also by Turner (2006, in Latulippe, 2015 p. 54) who argues that instead of isolation, the Two-Row-Wampum treaty embodies a relation of entangled interdependence. Such interdependence, Turner argues, is reflected in its Teioháte Kaswenta (two-row-wampum belt) which was created as a commemoration of this treaty. The rows of its purple wampum beads represent two vessels on a river; a ship (Dutch) and a canoe (Haudenosaunee). Each vessel, representing their respective nations, travels side-by-side down the rivers of ‘existence’, represented by the white rows of wampum beads. The agreement permits each side to ‘retain its integrity through undertaking its own process according to its own worldview. At the same time, the two sides share information and work in partnership on issues of common concern’ (McGregor, 2002 p.9). The two vessels rather than staying isolated share a space and are, although representing distinct polities, ‘inextricably entwined in a relationship of interdependence’ (Turner, 2006, in Latulippe, 2015 p. 54). This intertwining, importantly, does not pertain to the philosophical underpinnings of the cultures in encounter themselves, as this would lead to what Willie Ermine describes as ‘cultural confusion’; a state in which ‘we no longer know what informs each of our identities and what should guide the association with each other’ (Ermine, 2007 p. 197 ; see also Blackfoot elder Reg Crowshoe in AER, 2014). This is why it is so important for western scholars to find philosophical grounding for ‘entangled onto-epistemologies’ within their own western intellectual heritage, like for example within agential realism. In fact, this directly resonates with the second principle for ethical space, which I understand to be a respect for cultural boundaries. To engage on mutually agreed upon terms, requires practical negotiation across-, not overcoming philosophical differences between encountering cultures. Not only would overcoming such differences breach the integrity of the other who you seek to engage with, it is also from a practical perspective impossible to rethink relations based on ways of being and knowing that are not your own. Each culture therefore maintains its own autonomy, political- and cultural systems, but seeks to co-exists in a spirit of co-operation (Ermine, 2007 p. 200). The particular strength of formulating two such principles of ethical engagement, is that it not only points to concrete conditions for practices like knowledge braiding, or two-eyed-seeing to be implemented in mutually respectful ways, but also that it makes it possible to clearly point out a lack of such conditions for ethical encounter when they are absent. The ability to point out an absence of ethical conditions through the neglect of adhering to certain concrete principles of engagement, may more clearly identify challenges when they are encountered. For example, Broadhead and Howard more indirectly allude to such a lack of such conditions when they question whether one of the two eyes, one wishes to see with through the method of TES, is ‘essentially healthy’- and the other ‘partly diseased’? (2021 p.112). Reviewed through Ermine’s ESE, the partial ‘’disease’’ of the western eye, which is somewhat vaguely referred to by the authors, can more directly be understood as practices of euro-centrism through erasure, or in short, a practical lack of ‘willing engagement’. Another example of a lack of such conditions is provided by the founders of the TES method themselves (Bartlett et al., 2012), who extend on challenges they experienced during the process of setting up their Integrative sciences TES program in the larger institute of Cape Breton University (CBU). Here, it becomes clear that even though their program challenged the practices of philosophical dominance of western thinking, applied by itself it didn’t necessarily challenge the spaces associated with the institutional dominance of western thinking. What the ESE makes insightful through its principle of respectful distance and boundaries is that to facilitate practices of ethical engagement with each other, through for example an approach like TES, one must also negotiate terms of engagement for the emergence of such practices to emerge in a third space- dominated by neither. A lack of such an ‘ethical’ space may allow for one knowledge system and worldview to ‘subsume’ the other (Longboat, 2008; Nikolakis and Hotte, 2021), as Bartlett et al. (2012) describe eventually happening with the courses of the integrative science institute in CBU. To put it differently, understanding the ethical space as emerging from practice according to a set of principles clarifies that potential challenges to ethical knowledge relationships, or knowledge weaving in research, are not so much a question of philosophical incommensurability per se, but are more likely shaped by institutional limits, or lack of institutional mediation, practices and boundaries that emerge from the agential cuts- based on those differential philosophical paradigms. Being able to point towards (the lack of) concrete conditions and principles to create an ethical space of engagement protects against not merely rhetorical claims of third space endeavours, but also against the obscuring of such efforts under a scientific veil, as raised in round 2. In the early stages of writing my proposal and orienting myself in the relational webs of the project, I questioned the ethical ramifications of my intentions to explore the conciliatory potentials of genomic science with Inuit ways of knowing and being in the BearWatch project. Although some of these questions were technical; for example ‘would there be enough resources available for me to build the relational infrastructure necessary for meaningful collaboration with the Inuit project partners?’ They were mostly about relational im/possibilities; ’What prior relationships are already in place? Is there a basis of trust? What is my role as an ‘outsider?’ Would there be enough incentive from the PI’s to support a time and resource intensive ethical knowledge co-creation PhD project, when IQ engagement had so far predominantly consisted of data collection? Related to such risks and opportunities, I would now like to return to a point brought up earlier in round 2, in relation to the philosophical differences across western and Indigenous paradigms when it comes to the engagement with conceptual or theoretical models. As mentioned before, a closer scrutiny of such differences may help us design research with better conditions for ethical spaces and practices of engagement to emerge. That is, not by implementing the ESE as merely a model, principle or philosophy repositioning per se, but rather by letting it guide us to a research paradigm that allows for a process of respecting cultural difference. Of all three performative propositions of the ESE , this ‘process’ of ethical engagement is perhaps the most slippery of them all.

The ESE as a process of ethical engagement

Nikolakis and Hotte (2021) observe in their review on the application of the ESE in academic research, that the ESE emerges in practice as both a research approach, an ongoing practice, and a goal in itself. Although this observation confirms the entangled, onto-epistemological possibilities that meaningful engagement with ESE facilitates, such interchangeability of terms may also risk overlooking the complex manners in which ethics, theory and practice can intra-act. Or worse, it may de-link them in ways that undermine the principles of an ethical space. To drive home how so, I will briefly take you, for demonstration purposes only, on a journey that considers the ESE through a paradigm that upholds the onto-epistemological divides of post-positivist thinking. My goal by doing so is to clarify how attempts to work with models based on Indigenous paradigms, while holding onto such Cartesian divides will quickly lead to ethical trouble. This trouble is mainly caused by a logic that allows for the ESE to be operationalized as a generalizable, transferable and actionable model that may be inscribed in according to the particular context in which it is applied. This gap between model and relational context- allows for a separation of principle from practice, in similar ways that it separates theory from practice, or humans from nature. Let me explain. Principles, like those of ‘willing engagement’ and ‘respect for boundaries’, can be understood as rules or values that govern the way things work when it comes to the ESE. Such principles can be agreed upon between individuals, parties - or even nations. Let’s stick to the historical Two-Row-Wampum friendship treaty between the Dutch and Haudenosaunee of 1613 again as an example of such an agreement between nations. This agreement entailed, as mentioned, peaceful nation-to-nation coexistence between settlers and Indigenous peoples based on values of respect for distinct cultures while allowing for interaction and assisting each other as needed (see McGregor, 2004 p.86). The interpreting, organizing or presenting such principles in the form of a model can, in turn, depending on the organizational choices made, serve multiple purposes. Take the Teioháte Kaswenta, for example. Through an onto-epistemological divide, upholding Cartesian divides, this two-row-wampum belt belt could be seen as a mere representational or commemorative model of the agreements that were made between the Dutch and Haudenosaunee. Such a model would take its purple and white wampum beads representing two vessels on a river; a ship (Dutch) and a canoe (Haudenosaunee) and consider it a representative description of the particular principles of a contextual agreement. Such an interpretation would however also see its representative function decrease, or become irrelevant outside of this particular spatio-temporal moment, making it unfit as a prescriptive model outside of that context. It is here that trouble reveals itself. Although models are considered to be a common basis for how all humans organize socially across the globe, they are understood differently across cultures (Watts, 2013). Through western onto-epistemological divides, models of the ESE as published by the ISSAAK OLAM foundation, can be understood as an abstract Aristotelian idealization of a Two-Row-Wampum belt - a stripping of situational features towards an abstracted, more general, simplification (Frigg & Hartmann, 2006). My point here is not so much to trace down what kind of model the ESE, in the form that it is presented by ICE and the ISSAAK OLAM foundation could be categorized as within the western canon, but rather what the implications of such abstractions through a western epistemological interpretation are. When western epistemological Interpretations of the ESE as a model are employed from a disconnected positionality, they risk a generalization of what is actually particular, or a projecting of culturally appropriate ethics ‘’on top’’ of an abstract model of the ESE- a violation of the place-based nature of Indigenous knowledge (Deloria and Wildcat, 2001). The delinking of the researcher ‘’here’’, as an interpreter of the world that exists somewhere ‘’there’’, runs the risk of abstracting ethical engagement to a degree that it becomes disconnected from experience in the world. It risks what Deloria and Wildcat called a ‘Western intellectual asceticism’ (ibid p.17); the researcher as a detached observer. Considering the model of ESE, instead, in terms of the Indigenous cosmologies that it emerged from would reveal it as an animate and literal extension of creation itself (see Watts, 2013). From such an understanding the Two-Row-Wampum belt is much more than a representative model, or even a historical record. To suggest otherwise would be to disrespect the agency it inherently exerts as meaningful co-constituents for reconciliation efforts. Two-row-Wampum belts are living texts that are re-visited and re-’read’ through Indigenous stories, memories and performances (Haas, 2007 p. 80). The mutual relationships between treaty partners are, as such, honoured and kept alive. From this perspective, the responsibilities that are inextricably connected to the Two-Row-Wampum treaties remain, even when one of the partners fails to live up to them (ibid). When models are considered as animate and as extending beyond the moment of creation itself, it is furthermore not necessary to point out that the Two-Row-Wampum friendship treaty between the Dutch and Haudenosaunee of 1613 emerged from a particular, situated agreement. It would be redundant to explain that the meaning of the three white rows in the Two-Row-Wampum between the vessels extends specifically to peace, respect, and friendship, in accordance with Haudenosaunee philosophy which prioritizes reciprocity, and communal notions of respect as the basis of ongoing relationships (Turner, 2006 ; Latulippe, 2015). As Watts (2013 p. 27) explains; ‘a majority of Indigenous societies, conceive that we (humans) are made from the land; our flesh is literally an extension of soil. (...) If we begin from the premise that we are in fact made of soil, then our principles of governance are reflected in nature’. Following Watts’ explanation, such an artificial split between abstract model and particular (place-thought) inscription, makes no sense within Indigenous philosophies. Not because there are no cultural differences, but because all models would be considered the be a lived iteration of a particular place-thought- rather than a conceptual lens through which the world can be viewed from a distance- anyways. It is understood that each (non-)Indigenous society makes meaning of the world - and thus models- through their own relations and lived experiences (Kovach, 2010). Such an understanding of the ESE, doesn’t somehow mediate between ethical principle and cultural practice- nor does it have one follow from the other. The ethical space within an Indigenous research paradigm is rather ethical practice itself. Such a view on the ESE demonstrates the philosophical fallacy of trying to separate principle from practice and model when it comes to the ESE. For detached, and transcendent observers, model like that of the ISSAAK OLAM foundation above, could be considered stripped version of the-row-wampum; a prescriptive model that can be re-inscribed with Inuit-specific conceptualizations of ethical engagement (for example to be found in ICC, 2022). Agreements and treaties made in accordance with the ESE are however always situated and particular, rather than general and prescriptive. The ESE can only emerge as a result of ethical practices between cultures. Not imposed upon them. This by necessity, challenges both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers alike with questions of how to respectfully engage models like the ESE through methodological practices that are meaningful in the relational context which they are applied in (see Latullipe, 2015 ; Peltier, 2018 ; Reid et al., 2020). Being careful, deliberate and consistent in one's understanding of the ESE, rather than implementing its ethical, theoretical and practical potentials as interchangeable or separable, is therefore important if not crucial when it comes to achieving more ethical relationships. For me, such ethical engagement when it comes to applying the principles of the ESE in my research has emerged through an ethics of responsivity. This responsiveness is what Ingold calls ‘correspondence’ (Ingold, 2020), what Karen Barad refers to with the term of response-ability (Barad, 2007 p.172), and what is referred to across Indigenous cosmologies variously as practices of reciprocity or relational accountability. Whichever term holds meaning to your personal and cultural positioning, all quite literally point to various abilities of responsiveness, and presence.