Voices of Thunder

Point of beginning

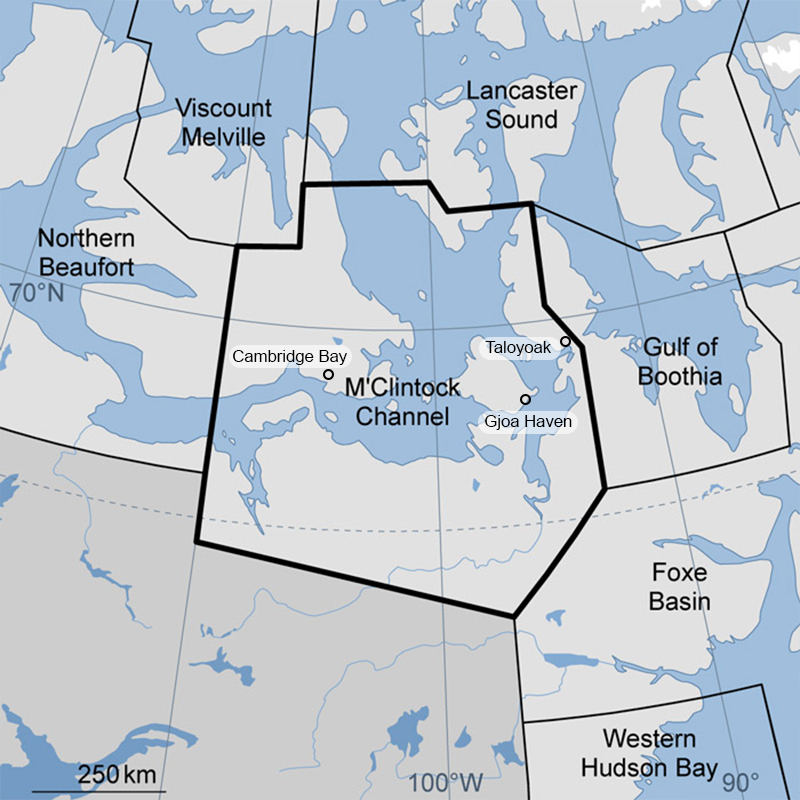

This manuscript/cut and its related work emerges from five years of ongoing conversations between representatives of the Gjoa Haven’s Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut (figure 1) and Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario researchers. It is based on a series of community-based workshops conducted in the summer of 2019 for a ‘Genome Canada’ sponsored large-scale polar bear monitoring project entitled “BEARWATCH: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge” – hereafter, simply, BW.

Several Inuit communities across Inuit Nunangat (homeland of Inuit of Canada’, ITK, 2018) have collaborated with the BW project to combine Inuit Knowledge with western science in developing a community-based, non-invasive, genomics-based toolkit for the monitoring and management of polar bears. One of these collaborating communities is Gjoa Haven, whose Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) representatives have a research relationship with BW co-PI Peter Van Coeverden De Groot that has stretched across more than 20 years. Over the years, one issue that was brought up repeatedly by Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and other community members, concerned the effects of severe polar bear hunting quota reductions introduced to the community in 2001.

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. Both Taloyoak and Cambridge Bay- unlike the residents of Gjoa Haven- however, also have traditional hunting grounds outside of the MC PBMU. So, when the quota in MC PBMU was significantly reduced from an average of 33 bears annually before 2000 (US FWS, 2001), to only 3 bears annually (NWMB, 2005), the community of Gjoa Haven was disproportionately impacted. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Hunting polar bears is an important part of Inuit culture. It facilitates inter-generational knowledge transmission of on-the-land skills, and provides a significant source of income within Inuit mixed-economies (Dowsley, 2008; Wenzel, 2011). After two generations of hardly being able to hunt polar bears, Gjoa Haven hunters still seek recognition for the impacts such quota-decisions have had in terms of lost income, loss of culture, and loss of intergenerational knowledge transfer.

This work invites you to accept testimony to these ongoing impacts of such severe quota reductions through the recorded experiences of Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. Such accepting testimony, however, isn’t limited to a ‘passive reading’ of the quota impacts on the community. You are instead invited to explore your own positioning- as a reader, a scientist, and collaborative meaning-maker responsively, alongside several other agential forces. What does it mean to ethically engage with these narratives? What responsibilities do we bear as readers? How are we implicated? What does it mean in the thick moment/um of reconciliation to share or accept testimony in accordance with the guiding principles of the Ethical Space of Engagement (Ermine, 2007)?

Text will be added here - see google doc

From purveying voices towards accepting testimony.

In the summer of 2019, two workshops were co-organized to discuss and document testimonies on the multiple impacts of the polar bear quota reductions on Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. The recordings of these workshops and its accompanying notes became the primary materials which were transferred to me, as a new PhD student on the BW project in 2020, to be described in an academic publication, and presented to a larger academic audience.

As a researcher who had not yet set foot in the community of Gjoa Haven, such an "assignment" made me feel uneasy; Who was I to write an academic paper that conveyed the lived experiences of people who I had never even met? Viewing the writing on such a sensitive topic as polar bear quota reductions, as a mere descriptive practice- disconnected from the wider research landscape within which they emerged- did not only strike me as unethical, it also seemed impossible. It is hard to separate the practices of a research project like BW, that is directly focussed on the methodologies of polar bear monitoring, from the subject of harvest quota- considering that quotas are set, at least partially, based on the insights derived from such monitoring efforts. As such, it seemed necessary to renegotiate my contributions in a way that provided for caution and with a sensitivity to how the BW project, and its non-Inuit researchers, are entangled with the larger legacy of scientific polar bear monitoring surveys and management processes that contributed to the impacts as shared in the workshop. Most crucial to such an approach became the extended conversations between the Gjoa Haven HTA representatives, myself and university-based BW PI’s.

Ongoing conversations

The choice to continue close collaboration between Gjoa Haven representatives and BW researchers, was crucial to a research approach that sought to ethically engage with the experiences that were shared in the impact workshops of 2019. Not only to decide on how to process, interpret and present the workshop recordings, but also to discuss the purposes to which the community had requested the workshops in the first place- and to navigate what role university-based researchers should, or could, play in achieving such purposes?

We arranged a total of five separate meetings between the Gjoa Haven HTA, myself, and multiple BW PI’s- each lasting about three hours to navigate a collective decision making on how to proceed with sharing these narratives. Due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic the first three of these meetings- and my introduction to the HTA-board- took place by remote conference phonecalls in 2020. Although these calls were not pre-structured or accompanied by an agenda, we did turn to a series of critical questions suggested by Linda Tuhawali Smith (1999) to guide us in our conversations; “What research do we want to do? Who is it for? What difference will it make? Who will carry it out? How do we want the research done? How will we know it is worthwhile? Who will own the research? Who will benefit?” Among multiple other insights, this led to a clear articulation of the main objective of Gjoa Haven HTA representatives for publishing the experiences shared in the workshops- collectively formulated as follows;

‘We want our “voices of thunder” to echo everywhere. We want everyone to know what happened to us. We seek acknowledgment and apologies for suffering the consequences of the quota regulations; a loss of culture and knowledge, as well as increased danger due to the rising number of polar bears around our communities. Inuit knowledge in terms of accuracy and inherent value needs to be recognized and better acknowledged. We want better integration of Inuit knowledge in survey research, like for example accounting for seasonal changes. Scientific monitoring surveys have limitations, we ask that researchers will recognize and take Inuit observations more seriously’.

The Gjoa Haven HTA seeks recognition. The kind of recognition that they seek is however multifaceted. Beyond acknowledgement and apologies for the quota reduction impacts, the Gjoa Haven HTA also seeks validation, and better “integration” of their knowledge in research and management. The Gjoa Haven board also speak of wanting to have their voices of thunder “echo everywhere” - a vision of broad dissemination that extends beyond the scientific community, towards other Nunavut communities and wider Canadian society. Academic publishing alone will likely not achieve this. To more completely pursue such desired forms of wide recognition, we realized that additional avenues of knowledge creation were needed in parallel to academic publishing. We subsequently co-created multiple audio/visual outputs that are better suited for broad dissemination through publicly accessible venues like social media, and internet, while we planned to co-produce one-pager communications that are more suitable for political advocacy.

The other outcome of our ongoing conversations is that it allowed for our collaborative work to better present Gjoa Haven’s voices and objectives, without the academic partners speaking for them. Instead of reproducing yet another damage-centered study that portrays an Indigenous community primarily as ‘broken, emptied, or flattened’ (Tuck, 2009), or the social scientists as an invisible and elevated ‘purveyor of voices’ for those that are suggested to be “voiceless” (Spivak, 1988 ; Simpson, 2007; Tuck and Yang, 2014)- we could explore how exactly each of our voices could be appropriately leveraged within different knowledge products.

Multiple voices

What initially was intended to be a unilateral descriptive (re)presentation of the recorded impacts of quota reductions as experienced by Gjoa Haven community members, slowly emerged to become a multi-vocal, co-creative process of engaging with these testimonies in ways that have been described as transformative to the relationship between some of the Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and the academic partners of BW.

Across the summer of 2021, and spring 2022, we arranged for an eight-week period of in-person co-creation and conversations in Gjoa Haven on how to proceed in sharing Gjoa Haven’s “Voices of Thunder”. During these periods, we discussed potential knowledge outputs and forms of writing- or otherwise- presenting the experiences shared in the workshops. We constructed narrative sequences and in 2021 we also started to co-produce on of our three main knowledge outputs; the motion graphic documentary In 2022, we reviewed versions of our academic paper, reconfirmed the meaning of several of the statements that were quoted in the workshop recordings through additional conversation, and we screened edited versions of several videos we had co-produced prior. Part of these processes, was to navigate the position of the academic scientists in ‘telling’ the story of quota reduction impacts for the community.

In each of our co-created research outputs, respectively i) a 20 minute co-created motion graphic documentary, ii) an academic publication, and iii) a webpage, the academic scientists of BearWatch and the community-members of Gjoa Haven are positioned differently. The academic partners always present themselves as explicitly visible actors, distinctly differently positioned from their Gjoa Haven partners, but not as detached on the one hand, or as ‘ventriloquists’ of the community of Gjoa Haven, on the other hand (see Spivak 2010, p. 27). Taking our cues from Jones and Jenkins (2008), we conduct a ‘negotiation of voice’- we make explicit who speaks, and how our collaborative authorship is navigated. To clarify which of our respective voices are present as this cut unfolds, I will state who ‘we’ refers to in each narrative output. The voices shift, for example, between ‘we’, as I use it here, which includes Gjoa Haven community representatives and the academic partners of the BW project, towards ‘we’ as it is applied within the motion graphic documentary, where it refers to Gjoa Haven’s hunters, community-members and HTA project partners exclusively. In parts of the academic paper, on the other hand, ‘we’ refers to the voices of academic research partners of the BW project only. Such visible differentiation and shifting of voices, both eliminates the impression that this paper addresses phenomena that are completely disconnected from the position of the BW scientists, while it also seeks to avoid speaking from one harmonized voice. Based on the tension of our differences, rather than attempting to erase them, we have sought to create multiple sites of enunciation, while maintaining a pragmatic collaboration across them.

For example, in the motion graphic documentary, the testimonies from the workshop participants on quota impacts speak for themselves. In the academic paper, on the other hand, the voice of the academic partners of BW are more prominently present. Not through the employment of theoretical frameworks and methodological analysis to translate, validate or otherwise explain the experiences shared by Gjoa Haven’s HTA representatives, hunters and community members, but rather by conducting a direct, ‘unromantic’, (sensu Jones and Jenkins, 2008) “testimonial reading”, as further elaborated on in section 1.3. A ‘testimonial reading’ facilitates an engagement with the experiences of Gjoa Haven’s community members that asks the reader to move beyond passive empathy towards an acceptance of testimony that requires bearing responsibility; it asks the reader to commit - to rethink their assumptions, to challenge the comfortable concept of being a ‘distant’ other, and to recognize the power-relationships between the reader and the testimonial text (Boler, 1997). By doing so, we can be guided both in our engagement with the experiences shared in the workshop, ànd our response to the appeal of the Gjoa Haven HTA for wider recognition.