Wayfaring the BearWatch Project

abstract

The incorporation of Inuit Knowledge in wildlife co-management and research is mandated by the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. Nevertheless, Inuit Knowledge in polar bear research is often selectively engaged with, rendered technical, and validated through scientific categories. This cut explores more explicitly the methodology of wayfaring as a potential transformative ethical practice of knowledge conciliation in the particular context of the community-based research of the BearWatch project. It narrates the project as a “netbag” story in which excerpts of project reports serve as a guiding cut, while reader and author correspond alongside it. Redirected by “ice-pressure ridges” and invites, such an intra-dependence performance of moving “alongside” facilitates a place-bases understanding of ethical engagement as a ‘knowing along the way’ (Ingold, 2010). Rather than rushing towards descriptive outcomes or conclusive take-aways, this cut allows us to make meaning with- both the physical, relational and the institutional landscape, and with the material dynamics of community-based fieldwork within the large-scale Genome Canada funded project; BearWatch. With the use of a knowledge-land-scape, comprised of (auto-) ethnographic materials derived from participatory observations, co-creative methods and interviews, this cut facilitates a rethinking of knowledge conciliation, beyond its usual focus on data, through an ethics of care and attention, while resisting linear, outcome-driven, and settler-centric practices.

Acknowledgements

An explicit note of acknowledgement for this cut should go out in particular to George Konana, in Gjoa Haven, and Leonard Netser in Coral Harbour. Both men have taken me out on the land, the sea and the ice on multiple occasions between 2020-2023. They patiently took time to introduce me to the land, answer my many questions, show and explain how they found their way across the land in various ways and under multiple conditions. Most valuable, however, is how they taught me to tag along and just be present for the ride.

1. Introduction

Polar bears have captured the public imagination for being charismatic and as one of the most politicized animals in the world (e.g. Strode 2017; Slocum 2004). There is little disagreement across cultures regarding polar bears as a species of importance, whether as a keystone predator, a sentinel of changing Arctic environments, a cultural icon, as a more-than-human relative, or a source of income through the guiding of sports hunts. The reconciliation of such differences within polar bear management is, on the other hand, less straightforward. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ, the Inuit way of knowing and being in the world) considers humans and bears, for example, to co-exist in a relationship that requires harmonic balance for it to remain ongoing (see for example Keith 2005; Karetak et al. 2017), while western formulations of wildlife conservation conceptualise polar bears, on the other hand, as a species in need of management to ensure its survival. The importance of reconciling such seemingly opposite ways in which polar bears matter across cultures, has increasingly been recognized, and even formalised through Territorial Land Claims Agreements across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit Homelands, see ITK, 2018).

The polar bear co-management regime in the Nunavut Settlement Area for example, is based on the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement (NLCA), which states that ‘Inuit must always take part in decisions on wildlife’ (NTI 2004), while ‘the guiding principles and concepts of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) are to be described and made an integral part of the management of wildlife and habitat’ (Wildlife Act 2003). Despite such formalised co-management, tensions remain. Significant data-gaps, and the international pressures to fill such gaps, as well as a rapidly changing Arctic environment and the difficulties of conciliating vastly different ways of knowing and being in wildlife conservation continue to haunt in particular the management and monitoring of polar bears in Inuit Nunangat.

This cut, focusses on the challenge of conciliating western sciences and IQ in community-based polar bear monitoring research. More precisely, it asks the question of what it means to practice knowledge conciliation under guidance of the principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE), as proposed by Sturgeon Lake, Ontario, Canada First Nation elder Willie Ermine , rather than based on data-driven needs.

To engage and answer such a question, under guidance of the ESE, entails- as will become clear- multiple shift. A shift of positioning; from distanced observer or reader to becoming an implicated “subject” – and a practical shift from operating based on fixed principles, to a practice of ongoing negotiations and ethical encounter. This shift applies also to you as a “reader” as you will engage with this “manuscript”. Within this knowledge-land-scape you are invited to shift from a reader to becoming a wayfarer.

2 Terms of engagement

To be a wayfarer, in opposition to being a traveller, is to be able to make decisions in-between and along the way. Wayfaring is not about crossing “over” from, or “across” point A to point B. It is about what happens on the way. When such a process is applied to the challenge of cross-cultural knowledge conciliation in line with the principles of the ESE, this also – as will become clear - entails a degree of shared meaning making with others. In this case, such others will include me. As such, and in line with the principles of the ESE, I want to propose some terms of engagement between us.

Firstly, it is possible to forgo this invitation to become a wayfarer. As you will enter and make your way across this knowledge-land-scape, you will have the possibility to keep following this “cut”, and read “about” my process of wayfaring the BearWatch project. Should you choose to accept (some of) my invitations (along the way), however, this should come with the understanding that such a decision entails your willingness to become an active and immersed agent in the ensuing material opening and closing opportunities for shared meaning-making within my research.

Secondly, the knowledge-land-scape, that you are about to enter is comprised of (digitized) materials. They are ethnographic traces like voice notes, photos, drawings, edited videos, written notes, posters and presentations, as well as academic texts and workshops, resulting from the more-than-human aesthetic encounters that were part of my fieldwork. My knowledge-land-scape is explicitly not about providing “direct” access to the land or Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (nor is such a thing possible, or desirable). It adheres to Inuit-driven EEE protocol 3 , in that it respects cultural “differences”. My work does not somehow make otherwise “remote” regions legible, accessible or available for consumption. Nor does it take the liberty to “represent” IQ, or “map out” Inuit Nunangat as if it were a blank slate, or “empty” space available for inscription or re-interpretation by non-Inuit researchers like me. As such this work doesn’t work towards descriptive representations of Inuit land or Knowledge. It acts instead as an emergent topology that consists of the insights that emerged as part of my research encounters, and materializes in-between subject-object, reader-author, and land-scape.

As such not everything is possible within this knowledge-land-scape. The land-scape as it emerges within this web-based platform is not meant to sketch a comprehensive and complete overview of the institutional or socio-political apparatus of community-based polar bear management. It is rather bounded by the particular more-than-human encounters of my fieldwork, the apparatus of western science and polar bear co-management, available resources and the technical affordances of the software with which it was built- as well as the intra-dynamics of all these matters and my decisive cuts as a researcher.

As you try to figure out what this concretely means, you sport a formation of rocks. You could take a moment to orient and prepare for your upcoming journey. If you step onto this rock right next to you, you will get a better view of your surroundings. It perhaps provides possibilities to gain some deeper understanding of what such shared-meaning making and its boundaries have to do with knowledge conciliation and the ESE. Otherwise, you could just get going and learn more about how I positioned myself within the BearWatch project.

3. The BearWatch project

The track you are currently following will cut along the unfolding developments of the Genome Canada funded research project called ‘Bearwatch: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge’ – hereafter referred to as ‘Bearwatch’. Bearwatch ran between 2015 and 2023, during which it sought to meaningfully engage IQ in its development of a new non-invasive genomic polar bear monitoring toolkit. The project was a collaboration between northern communities in the Nunavut Settlement Region and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, HTAs in Gjoa Haven and Coral Harbor, the Inuvialuit Game Council, the governments of Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon, the Canadian Rangers, and researchers and students from multiple universities across Canada and beyond.

Most researchers and policymakers in the field of polar bear science more generally – and on the BearWatch project particularly – are trained in a variety of natural science disciplines of the western academic institute, or they are Inuit knowledge and rights holders. I, myself, am a white, queer, settler-guest researcher from the Netherlands with a background in the applied arts and social sciences. Approaching this research context as a non-Inuit researcher from such a different cultural and disciplinary place of beginning than most other Bearwatch team members and polar bear monitoring practitioners, has required me to negotiate and navigate my own way alongside many of the project’s activities.

This particular cut allows you trace the unfolding of the BearWatch project along multiple (sometimes parallel) tracks in a manner that also allows for you to thread your own way through this knowledge-land-scape. As such, this cut is not so much about deriving at conclusive take-aways about ethical knowledge conciliation within BearWatch, as much as it about extending material opportunities for you, the reader, to become knowledgeable alongside my creative practice (auto-)ethnography with the research project.

4 Point of decision-making

Before you head further down this cut, you have a choice to make. Will you trace the most straightforward path across the BearWatch project, engaging just with the descriptive elements of my research? Or will you thread your own way alongside me, becoming an intra-dependent maker of meaning? The former choice will be a more disconnected, conventional experience, whereas the latter will be more of an immersed narration, that places you “within” my knowledge-land-scape.

In this line of thought you realize it might be helpful to look up the meaning of “intra” dependency, as opposed to “interdependency”. Then you realize this entails taking off your mitts and taking your phone out of your pocket. It’s freezing, and your phone might not last long in these temperatures. If you choose to keep going instead, you will move straight to reading about the TEK workshops that were held in the community of Gjoa Haven in 2019, as to inform a feasibility study on future community-driven polar bear fecal sample collection.

Detour: look up the meaning of "intra-dependency"

5. TEK workshops

Polar bear populations- and thus Indigenous harvesting- are, under the international agreement on the conservation of polar bears, to be managed ‘in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best available scientific data available’ (Lentfer, 1974). The NLCA states furthermore that ‘Inuit must always take part in decisions on wildlife’ (NTI 2004), while part 1 of its wildlife act, states that ‘the guiding principles and concepts of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) are to be described and made an integral part of the management of wildlife and habitat’ (Wildlife Act 2003).

In response to the ‘legal authority of land claim agreements, asking that IQ/TEK be used to make management decisions’, and ‘to increase community ownership of polar bear monitoring through community-based collection and knowledge sharing’ the BearWatch project was designed to include a “Genomics and its Environmental, Economic, Ethical, Legal and Social aspects (GE3LS)” component (BearWatch research proposal, 2016 p.30-31).

As part of this GE3Ls activity three TEK mapping workshops were co-designed with the HTA of Gjoa Haven to ‘identify TEK gaps’ and ‘fill them’. The temporal and spatial polar bear TEK that was collected, was processed and published in the MES thesis of Scott Arlidge, another student that participated in the project. It ‘provides a georeferenced knowledge base that displays information on polar bears including harvest sites, bear movement, denning sites, and hunter knowledge areas’ (Arlidge, 2022 p.13). The data as shared in this publication is presented in his thesis as i) ‘a historical record of polar bear knowledge for the community of Gjoa Haven’; and ii) ‘as a guide to areas of high polar bear activity for future targeted polar bear monitoring effort’s’ (Arlidge, 2022 p.ii).

You have taken a moment to sit down and read Arlidge's thesis. As you are about to check out what Genome Canada has written on their website about GE3LS, someone brings up the existence of a nearby shipwreck: Knowledge “integration”. They suggest you go check it out to get another perspective on bringing IQ together with western sciences.

You weigh your options, as there is also another workshop lined up for tomorrow. The Gjoa Haven HTA has urgently been trying to get the BearWatch researchers to turn their focus towards the available polar bear harvest quota. 20 people will come to talk about how a harvesting moratorium from 2001 has had reverberating impacts on them up until today. You should keep moving, because you were asked to buy coffee and snacks for that meeting.

Wrecksite:Knowledge "inclusion"

1.2 Wayfaring

Ingold (2010) describes the wayfarer as ‘a being who, in following a path of life, negotiates or improvises a passage as he goes along’ (Ingold, 2010 s126). Wayfaring is a body-on-the ground, material way of knowing that emerges along the course of everyday activities, rather than built up, gathered or collected from ‘fixed locations’. Rooted in the ‘weather-world’ of complex entanglements and partial perspectives, it drives the research along as a process that is unfixed, fluid and in constant motion of coming to know-, or becoming -other. As a transcultural, methodological practice, I argue that a process of wayfaring allows for ethical knowledge conciliation to be understood as a space, practice and process of engagement, that can take place in correspondence with the Ermine’s ethical Space of Engagement (ESE, 2007)- instead of as a data-driven endeavour. Knowledge can be seen as ongoing, fluid and place-based, rather than frozen in time, packageable and exportable. It makes it possible to attune to the seasons and make meaning through navigating both the physical, relational and the institutional landscape through an ethics of care and attention.

In its simplest form, wayfaring is a practice of responding, correspondence, and of practicing one’s own response-ability. Relying on such response-ability in this knowledge-land-scape is the difference between an open-ended, future-oriented practice of collective sense-making, and a dead-end, unidirectional trajectory of me guiding you towards a description of best research practices in accordance with publicly available Inuit guidelines on ethical engagement, like for example those of the ICC’s ‘circumpolar Inuit protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement’ (2022) or the National Inuit Strategy on Research (ITK, 2018). This proposition is not in any way meant to discredit such guidelines. It rather points out that such guidelines will not be very effective if they are not being responded to or enacted with gestures of meaningful intent.

The publication of such guidelines can perhaps be, in following with Ingold, compared to the lines of an architectural drawing. Such lines are a descriptive gesture, an instruction. What we get to read in the publication of such guidelines, is the final result of a creative process; an instructive product about protocols, rather than insights of the productive process that has brought these protocols themselves into being. In other words, the 2022 ICC publication can be understood as a trace of agreements about ethical engagement, rather than as an active practicing of ethical engagement itself. It is hard to be in lively correspondence with a trace – beyond, of course, the act of narrowly following it to its final destination. Such a trace tells a story, but it is itself not story-ing: it doesn’t move, change or respond in relation to your engagement with it. For such lively intra-action, correspondence, or relational resonance, one needs to consider guidelines on ethical practices as a multi-directional verb. Not a retro-spective trace-ing, but rather for example a prospective thread-ing (Ingold, 2020 p.181).

The difference between the trace and the thread as an intentional practice of moving through the world is directional. The trace is both retro- and/or prospective, it describes a one-sided story of a past or future event. The thread, perhaps as a ball of yarn -as Ingold asks us to think about it- is on the other hand, neither retro- nor prospective. It is emergent, and winds or unwinds as you proceed through the world with it (Ingold 2020). This emergent quality of continuously opening up to the world is what makes the thread alive and respondent. To wayfare as a thread, is not so much about moving forward, or towards something, but is rather about transformation. A movement in which nothing remains static; nature- and the researcher included -become emergent; being necessarily turns into becoming, and representing turns into performing ongoing movement. This is what navigating the knowledge/land/scape affords. It allows for you, as a reader to engage, return, and be in correspondence with my research. It is an ongoing process of re-positioning.

1.3 Wayfaring the BearWatch project

The explorative goal of this cut is therefore, not so much to argue for a specific outcome or practice of knowledge relating, but rather to deepen our understanding of how, as researchers operating with(in) the traditions and institutes of western science, we can practice ethical research under open-ended conditions of uncertainty. In pursuit of such a goal, I have moved away from presenting solutions, towards facilitating a process of becoming.

This cut performs certain key-moments of the BearWatch project that took place during the period that I was part of the project, as possible sites of encounter and ethical engagement. You are invited to follow along the unfolding of the project through these key moments. They are performed as sites of diffractive im/possibilities between narrative vignettes, ethical dilemmas, research-creations, and auto-ethnographic fieldnotes that emerged from my own practice-based engagements within the communities of Gjoa Haven and Coral Harbour. Along the way in-between such sites you are either re-directed by the material forces of emergent ice-pressure ridges (a land-based metaphor for the more-than-human agencies that intra-act to shape the conditions under which some of this work has taken place), or invited to trail-off on unexpected side-tracks (which perform the possibility of wandering). Such redirections provide possibilities to orient or gain emergent insights on what it means within this particular research context to practice polar bear research as an ethical space, or process of engagement.

Deriving value from this work requires immersion and attentiveness. Such is the futurity that this dissertation aims to enable and contribute to; extended ethical knowledge encounters between Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge holders, multidisciplinary research teams, and academic readership, based on ethical and attentive engagement. Remaining a distanced spectator will not do. As such, this cut starts by taking you along to a series of workshops that were conducted in Gjoa Haven, during the Summer of 2019.

5. Workshops Summer 2019

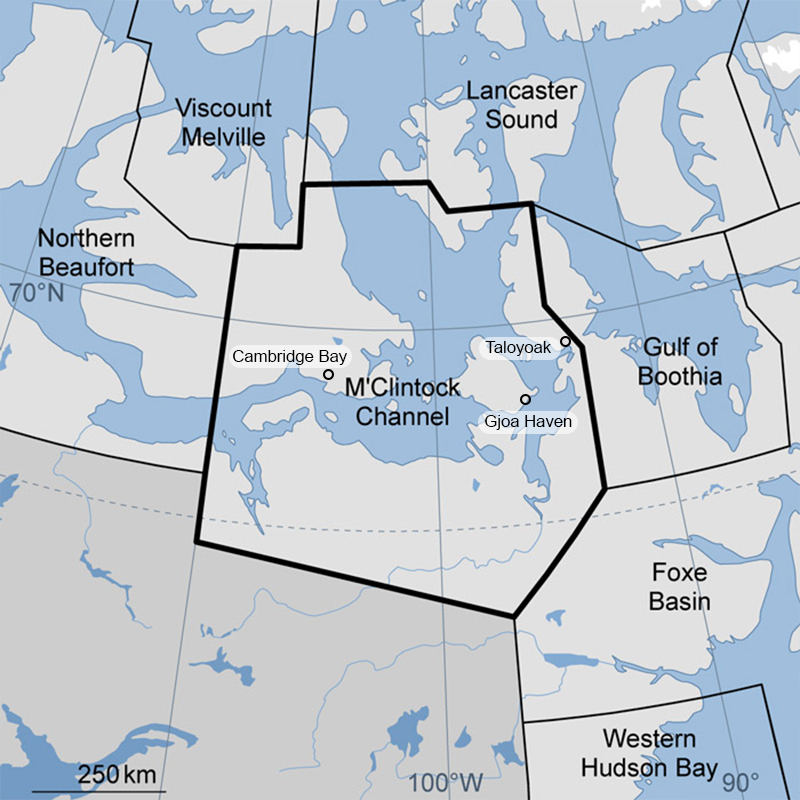

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Based on a desire for recognition and acknowledgement of the impact of these polar bear quota regulations, two workshops were co-organized in addition to the original TEK workshops that were planned to take place over the summer of 2019, to discuss and document the testimonies of Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members

The workshops were advertised over the radio in both English and Inuktitut (Inuit language), and interested individuals signed up through the HTA. One workshop was held May 15, 2019 in the evening with 10 participants and one on May 16 in the morning with 11 participants. These participants comprised mainly older male community members, many of whom had hunted, or still hunt polar bears. There were two female participants in each workshop. Three of the participants were between the ages of 20 and 40, with the remainder older. These two workshops focused specifically on the impacts of polar bear hunting quota reductions on the community. The workshop questions were co-designed by the BW academic researchers and HTA representatives and were asked in both English and Inuktitut to prompt discussion. The format however remained open-ended, meaning that "off-script" discussions were encouraged during the workshop, and occasionally specific members were asked to participate in answering particular questions because of their connection to the issue, as identified in previous interviews or by other community members. Two BW researchers and an interpreter would ask the pre-designed questions and prompt discussion, while a third BW researcher made notes. Both workshops were audio-recorded.

These recordings and workshop notes became the primary materials which were given to me, not long after I joined the BearWatch project. I was requested to describe these experiences and share them with a larger academic audience through academic publishing. This request however presented me with multiple dilemmas.

What to do?

Although you understand that writing “about” other people’s experiences doesn’t exactly sound ethical, you have little time and need to keep going. Your first fieldwork trip to Coral Harbour is upcoming, and you need to prepare for that. Besides, the Gjoa Haven HTA wants a publication, no need to complicate things further. Alternatively you can stay with the trouble and explore in what ways the “Politics of recognition” complicates such writing practices. Maybe you have already leaned into such tensions, and all that is left now, is to organize a conference call and have a conversation with the Gjoa Haven HTA about these complexities.

Stay with the trouble: The politics of recognition

Return to Cut 1 Voices of Thunder"

4. Coral Harbour First trip 2020

Alongside funding from Genome Canada, the project PI’s also successfully applied to the Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada/ World Wildlife Fund to fund ‘traditional knowledge research and a denning survey in Coral Harbour, Nunavut’ (Schedule H, 2020, March 31. This intended study included documenting polar bear TEK in Coral Harbour, surveys of vacated dens by locals to collect a variety of samples and data, and the initiation of a collaborative effort with the high school to train students in land-based surveys. These activities were planned for March and April, but were postponed due to COVID-19. The Hamlet of Coral Harbour requested outside visitors stay away the day before most of the BearWatch team was set to arrive in the Hamlet, and the BearWatch PI’s respected their wishes.

I had, however, travelled North a day early, and arrived in the community on exactly the day that the Covid-19 epidemic was declared pandemic. Non-resident travel bans came into effect in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, as well as physical distancing requirements within communities. Having travelled up to Coral Harbour during early spring, the weather was changeable, and indeed took a turn after my arrival. Despite immediately rescheduling my flight back South, my departure from Coral Harbour got postponed by multiple days of blizzards. During these days I was welcomed, kept company and supported by Leonard Netser, Coral Harbour based BearWatch PI, and his family. Having never travelled to the North, and without the other BearWatch team members present, the situation allowed for Leonard and I to become acquainted with each other, in way that has allowed for an ongoing rapport between the two of us as the project unfolded.

One of the most influential moments of my PhD took place during those “lost” days that I was not able to fly out from Coral Harbour due to morning blizzards- Leonard invited me along on a Caribou hunting trip.

You're invited to join along for a Caribou hunt.

Ice pressure ridge: Spring in Coral Harbour

Covid-19

When the spread of Covid-19 was declared a pandemic it shaped an ice-pressure ridge that was so immense, that it not so much required me to redirect- as it asked me to re-position. Both figuratively and literally. Having just arrived in Coral Harbour, for my first fieldwork trip and my first travel up North, I was requested upon arrival to return immediately. The pandemic was declared while I was in the air, and by time I landed the local “Northern” store, like many other stores across the country, was sold out of toiletpaper and hand sanitizer. As described above, I was, nevertheless, warmly welcomed by local PI Leonard Netser and his family- who made sure I was comfortable.

This pandemic has functioned as a double-edged sword. On the one hand it has caused a significant delay, and obstruction in terms of building community relations in the field. After I was finally able to leave Coral Harbour once the blizzards had ended, it took almost a year and a half before I could return North again, and start building relationships in the way that they are built most effectively- in person, and on the land. On the other hand, it has also allowed for more time to think about how to contribute to the BearWatch research project, in a way that honours my professional background, and ethical values. It has also opened pathways to initial remote connections with research partners in Gjoa Haven through communication platforms like zoom and conference calls. Nonetheless, the endemic has had significant and lasting impacts on the material circumstances under which I continued to work on my PhD.

Covid-19 Remote interviews

‘Our territorial government collaborators are currently working from home with no field work permitted for the foreseeable future, and southern labs remain closed. We are working on plans to achieve our community goals remotely, but the full impact of COVID-19 on both lab work and field work remains to be seen.’

This was written as part of the schedule H report (March, 31, 2020), by BearWatch PI de Groot.

Fieldtrip BW team Coral Harbour Summer 2021

You're invited to join along for a drive around the island.

Ice pressure ridge: Summer in Coral Harbour

Fieldtrip BW team Gjoa Haven Summer 2021

HTA meetings presentations

Voices of thunder meetings

Stranding the car

ATV ride

The environmental conditions in Inuit Nunangat seem initially a fitting context to easily debunk anthropocentric ontologies. For example, any visiting researcher who has tried to prepare, pack or pull a qamutiq (sled) across the land outside of Arctic Summer for the first time, like I did in 2021, has likely encountered the limits of human agency as well as the particular teachings of humility. The land itself invites one to move away from anthropocentric tellings - towards narrations of becoming knowledgeable in company with the seasons, snow, ice, wind, rocks, and caribou. Such stories leave room for us as researchers, but are importantly not about us. Donna Haraway calls such stories “netbag stories” (2016, p.38). She argues, inspired by Ursula le Guin (1986), that the kind of stories we need telling in these times are not those of the Antropos. Not those of the capitalized Human in History and all the weaponized tools such a Human might carry, but those of the netbag, the basket, or any other concave shape. Such a netbag, or even a pair of cupped hands enables carrying things along, and receiving and giving away. Such exchange suggests ongoing stories of becoming with-; a collective making and unmaking of the world with ‘companion species’ as ‘kin’ (Haraway, 2003 ; 2016). These stories acknowledge messy, earthbound, multispecies entanglements, rather than man-making tales of the single hero.

Camping at the Weir

Invitation:Trail-off to understand better how my whereabouts influenced my writing, reading and broader relationship to the country after this fieldtrip

Meetings Spring 2022 Gjoa Haven

Checking seal dens

Collecting ice

Meetings Spring 2022 Coral Harbour

Spending time in Yan's Cabin

Qamutiq building and riding

Walking the same road every day

Seasonal changes

Illness

Gender based violence

In text link to Point of Beginning Mx. Science

Fall 2022 Coral Harbour

In text link naar Design consultation pre-workshop & workshop Coral Harbour

remote planning

illness

tension

absence

Wayfaring Calendar pilot

In text link naar Another point of beginning Wayfaring method

Arctic travel

Fall 2022 Gjoa Haven

In text link naar Design consultation pre-workshop & workshop Gjoa Haven

Preparing cabin pre-workshops

Cooking/ Sharing food

Prayer

Truck Flat Tire

In text return to Preparation Gjoa Haven workshop in the Workshop Gjoa Haven trace.