Voices of Thunder

Point of beginning

Abstract

Introduction

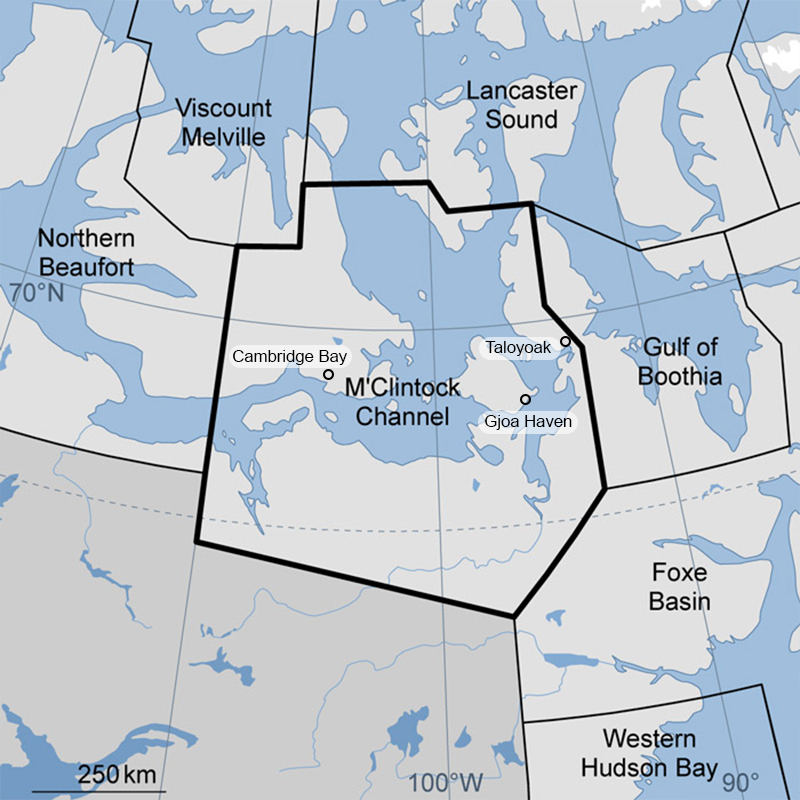

This manuscript/cut and its related work emerges from five years of ongoing conversations between representatives of the Gjoa Haven’s Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut (figure 1) and Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario researchers. It is based on a series of community-based workshops conducted in the summer of 2019 for a ‘Genome Canada’ sponsored large-scale polar bear monitoring project entitled “BEARWATCH: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge” – hereafter, simply, BW.

Several Inuit communities across Inuit Nunangat (homeland of Inuit of Canada’, ITK, 2018) have collaborated with the BW project to combine Inuit Knowledge with western science in developing a community-based, non-invasive, genomics-based toolkit for the monitoring and management of polar bears. One of these collaborating communities is Gjoa Haven, whose Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) representatives have a research relationship with BW co-PI Peter Van Coeverden De Groot that has stretched across more than 20 years. Over the years, one issue that was brought up repeatedly by Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and other community members, concerned the effects of severe polar bear hunting quota reductions introduced to the community in 2001.

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. Both Taloyoak and Cambridge Bay- unlike the residents of Gjoa Haven- however, also have traditional hunting grounds outside of the MC PBMU. So, when the quota in MC PBMU was significantly reduced from an average of 33 bears annually before 2000 (US FWS, 2001), to only 3 bears annually (NWMB, 2005), the community of Gjoa Haven was disproportionately impacted. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Hunting polar bears is an important part of Inuit culture. It facilitates inter-generational knowledge transmission of on-the-land skills, and provides a significant source of income within Inuit mixed-economies (Dowsley, 2008; Wenzel, 2011). After two generations of hardly being able to hunt polar bears, Gjoa Haven hunters still seek recognition for the impacts such quota-decisions have had in terms of lost income, loss of culture, and loss of intergenerational knowledge transfer.

This work invites you to accept testimony to these ongoing impacts of such severe quota reductions through the recorded experiences of Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. Such accepting testimony, however, isn’t limited to a ‘passive reading’ of the quota impacts on the community. You are instead invited to explore your own positioning- as a reader, a scientist, and collaborative meaning-maker responsively, alongside several other agential forces. What does it mean to ethically engage with these narratives? What responsibilities do we bear as readers? How are we implicated? What does it mean in the thick moment/um of reconciliation to share or accept testimony in accordance with the guiding principles of the Ethical Space of Engagement (Ermine, 2007)?

Text will be added here - see google doc

From purveying voices towards accepting testimony.

In the summer of 2019, two workshops were co-organized to discuss and document testimonies on the multiple impacts of the polar bear quota reductions on Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. The recordings of these workshops and its accompanying notes became the primary materials which were transferred to me, as a new PhD student on the BW project in 2020, to be described in an academic publication, and presented to a larger academic audience.

As a researcher who had not yet set foot in the community of Gjoa Haven, such an "assignment" made me feel uneasy; Who was I to write an academic paper that conveyed the lived experiences of people who I had never even met? Viewing the writing on such a sensitive topic as polar bear quota reductions, as a mere descriptive practice- disconnected from the wider research landscape within which they emerged- did not only strike me as unethical, it also seemed impossible. It is hard to separate the practices of a research project like BW, that is directly focussed on the methodologies of polar bear monitoring, from the subject of harvest quota- considering that quotas are set, at least partially, based on the insights derived from such monitoring efforts. As such, it seemed necessary to renegotiate my contributions in a way that provided for caution and with a sensitivity to how the BW project, and its non-Inuit researchers, are entangled with the larger legacy of scientific polar bear monitoring surveys and management processes that contributed to the impacts as shared in the workshop. Most crucial to such an approach became the extended conversations between the Gjoa Haven HTA representatives, myself and university-based BW PI’s.

Staying with the trouble: Politics of recognition

Ongoing conversations

The choice to continue close collaboration between Gjoa Haven representatives and BW researchers, was crucial to a research approach that sought to ethically engage with the experiences that were shared in the impact workshops of 2019. Not only to decide on how to process, interpret and present the workshop recordings, but also to discuss the purposes to which the community had requested the workshops in the first place- and to navigate what role university-based researchers should, or could, play in achieving such purposes?

We arranged a total of five separate meetings between the Gjoa Haven HTA, myself, and multiple BW PI’s- each lasting about three hours to navigate a collective decision making on how to proceed with sharing these narratives. Due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic the first three of these meetings- and my introduction to the HTA-board- took place by remote conference phonecalls in 2020. Although these calls were not pre-structured or accompanied by an agenda, we did turn to a series of critical questions suggested by Linda Tuhawali Smith (1999) to guide us in our conversations; “What research do we want to do? Who is it for? What difference will it make? Who will carry it out? How do we want the research done? How will we know it is worthwhile? Who will own the research? Who will benefit?” Among multiple other insights, this led to a clear articulation of the main objective of Gjoa Haven HTA representatives for publishing the experiences shared in the workshops- collectively formulated as follows;

‘We want our “voices of thunder” to echo everywhere. We want everyone to know what happened to us. We seek acknowledgment and apologies for suffering the consequences of the quota regulations; a loss of culture and knowledge, as well as increased danger due to the rising number of polar bears around our communities. Inuit knowledge in terms of accuracy and inherent value needs to be recognized and better acknowledged. We want better integration of Inuit knowledge in survey research, like for example accounting for seasonal changes. Scientific monitoring surveys have limitations, we ask that researchers will recognize and take Inuit observations more seriously’.

The Gjoa Haven HTA seeks recognition. The kind of recognition that they seek is however multifaceted. Beyond acknowledgement and apologies for the quota reduction impacts, the Gjoa Haven HTA also seeks validation, and better “integration” of their knowledge in research and management. The Gjoa Haven board also speak of wanting to have their voices of thunder “echo everywhere” - a vision of broad dissemination that extends beyond the scientific community, towards other Nunavut communities and wider Canadian society. Academic publishing alone will likely not achieve this. To more completely pursue such desired forms of wide recognition, we realized that additional avenues of knowledge creation were needed in parallel to academic publishing. We subsequently co-created multiple audio/visual outputs that are better suited for broad dissemination through publicly accessible venues like social media, and internet, while we planned to co-produce one-pager communications that are more suitable for political advocacy.

The other outcome of our ongoing conversations is that it allowed for our collaborative work to better present Gjoa Haven’s voices and objectives, without the academic partners speaking for them. Instead of reproducing yet another damage-centered study that portrays an Indigenous community primarily as ‘broken, emptied, or flattened’ (Tuck, 2009), or the social scientists as an invisible and elevated ‘purveyor of voices’ for those that are suggested to be “voiceless” (Spivak, 1988 ; Simpson, 2007; Tuck and Yang, 2014)- we could explore how exactly each of our voices could be appropriately leveraged within different knowledge products.

Pressure ridge: How Covid-19 redirected and my unfixed my personal whereabouts

Invitation:Trail-off for the material realities of working and writing from the road during fall 2020 during covid-19

Multiple voices

What initially was intended to be a unilateral descriptive (re)presentation of the recorded impacts of quota reductions as experienced by Gjoa Haven community members, slowly emerged to become a multi-vocal, co-creative process of engaging with these testimonies in ways that have been described as transformative to the relationship between some of the Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and the academic partners of BW.

Across the summer of 2021, and spring 2022, we arranged for an eight-week period of in-person co-creation and conversations in Gjoa Haven on how to proceed in sharing Gjoa Haven’s “Voices of Thunder”. During these periods, we discussed potential knowledge outputs and forms of writing- or otherwise- presenting the experiences shared in the workshops. We constructed narrative sequences and in 2021 we also started to co-produce on of our three main knowledge outputs; the motion graphic documentary In 2022, we reviewed versions of our academic paper, reconfirmed the meaning of several of the statements that were quoted in the workshop recordings through additional conversation, and we screened edited versions of several videos we had co-produced prior. Part of these processes, was to navigate the position of the academic scientists in ‘telling’ the story of quota reduction impacts for the community.

In each of our co-created research outputs, respectively i) a 20 minute co-created motion graphic documentary, ii) an academic publication, and iii) a webpage, the academic scientists of BearWatch and the community-members of Gjoa Haven are positioned differently. The academic partners always present themselves as explicitly visible actors, distinctly differently positioned from their Gjoa Haven partners, but not as detached on the one hand, or as ‘ventriloquists’ of the community of Gjoa Haven, on the other hand (see Spivak 2010, p. 27). Taking our cues from Jones and Jenkins (2008), we conduct a ‘negotiation of voice’- we make explicit who speaks, and how our collaborative authorship is navigated. To clarify which of our respective voices are present as this cut unfolds, I will state who ‘we’ refers to in each narrative output. The voices shift, for example, between ‘we’, as I use it here, which includes Gjoa Haven community representatives and the academic partners of the BW project, towards ‘we’ as it is applied within the motion graphic documentary, where it refers to Gjoa Haven’s hunters, community-members and HTA project partners exclusively. In parts of the academic paper, on the other hand, ‘we’ refers to the voices of academic research partners of the BW project only. Such visible differentiation and shifting of voices, both eliminates the impression that this paper addresses phenomena that are completely disconnected from the position of the BW scientists, while it also seeks to avoid speaking from one harmonized voice. Based on the tension of our differences, rather than attempting to erase them, we have sought to create multiple sites of enunciation, while maintaining a pragmatic collaboration across them.

For example, in the motion graphic documentary, the experiences shared by the workshop participants speak for themselves, through the voices of Gjoa Haven community members. In the academic paper, on the other hand, the voices of the BW scientists are more prominently present. Not through the employment of theoretical frameworks and methodological analysis to translate, validate or otherwise explain the experiences shared by Gjoa Haven’s HTA representatives, hunters and community members, but rather by conducting a direct, ‘unromantic’, (sensu Jones and Jenkins, 2008) “testimonial reading”, as further elaborated on in section 1.3. A ‘testimonial reading’ facilitates an engagement with the experiences of Gjoa Haven’s community members that asks the reader to move beyond passive empathy towards an acceptance of testimony that requires bearing responsibility; it asks the reader to commit - to rethink their assumptions, to challenge the comfortable concept of being a ‘distant’ other, and to recognize the power-relationships between the reader and the testimonial text (Boler, 1997). By conducting such a testimonial reading of the experiences shared by Gjoa Haven community members, we can both engage with the experiences shared in the workshop, ànd the appeal of the Gjoa Haven HTA for wider recognition, in a way that aligns with the principles of Ethical Space of Engagement (Ermine, 2007).

Testimonial reading

Terms like ‘testimony’ or ‘witnessing’ are ideologically and politically loaded, and may mean different things within different contexts. To ‘witness’, when considered in the context of this cross-cultural research collaboration, doesn’t take up the western legal definition of being an (eye)witness as it would in the context of a legal court. It rather takes up meaning that aligns more with Indigenous traditions of witnessing, in the way it was applied in the public fora of Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Committee hearings, for example. Witnessing, as defined in schedule N and later on the TRC website (TRC.ca), is to take responsibility for ‘accepting testimony’ on historical events, even if one hasn’t directly experienced these events themselves.This form of witnessing is active. It is not merely listening. To witness, is to enter into a very specific and powerful relationship between witness and storyteller (Nock in Gaertner, 2016 p.138). This form of witnessing is particularly important to Indigenous cultures that use oral traditions. “Oral traditions form the foundation of Aboriginal societies, connecting speaker and listener in communal experience and uniting past and present in memory.” They are “the means by which knowledge is reproduced, preserved and conveyed from generation to generation” (Hulan & Eigenbrod in Gaertner, 2016 p.139). In other words, accepting testimony comes with responsibilities. Whether these are responsibilities to remember, or a commitment to take forward, teach others and spread the word- accepting testimony is not a passive act, nor a one-time event.

This act of witnessing and giving testimony between Inuit community members and non-Inuit BW researchers begins, in the case of our research, when BW researchers acted in response to the issue of quota reductions, as raised by their Gjoa Haven partners. By resourcing, planning, and co-designing two workshops with Gjoa Haven HTA representatives to take place in the community, the space was created to engage in the kind of attentive listening that is needed to meaningfully accept testimony; the kind of listening that changes you, and connects you to the speaker. The recording and documenting of the process could be understood as another part of accepting testimony; the commitment to “take forward” and “spread the word”. There are however tensions involved with these latter practices when it comes to the cross-cultural partnership of the BW project. Primarily the fact that these understandings of accepting testimony derive from Indigenous traditions, and that, as explained above, there are risks and power dynamics at play when western, non-Indigenous researchers take on the responsibility of sharing Indigenous testimonies in academic publications- for academic audiences. Different forms of knowledge outputs, presence of voices, and anticipated “listeners” require different approaches to accepting testimony. For the academic publication, the BW researchers have chosen to accept testimony by conducting a ‘testimonial reading’.

Megan Boler (Boler, 1997, p.255), who named the method of ‘testimonial reading’, places the act of taking responsibility central in her work on reading testimony. She wrote; ‘’While empathy may inspire action in particular lived contexts (…) I am not convinced that empathy leads to anything close to justice, (or) to any shift in existing power relations’’. To shift such relations, ‘’one must recognize oneself as implicated in the social forces that create the climate of obstacles the other must confront’’ (ibid, p. 257). Suggesting a practice of accepting testimony by which a reader or listener places themselves as implicated with the events one accepts testimony for, aligns with some of the guiding principles for reconciliation as put forward by the TRC (TRC, 2015c p. 113). These principles consider reconciliation as an opportunity to practice an ‘awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour’ (ibid). In other words ‘The TRC (...) puts responsibility for change squarely on the shoulders of all Canadians’ (McGregor, 2018 p.823 emphasis mine)- not just the Indigenous people who take up responsibility for sharing their experiences publicly.

To conduct a testimonial reading of the impact of quota reductions, as shared by Gjoa Haven community members, thus requires the academic partners of BW to assess how they themselves are entangled with the institutional apparatus that has facilitated the lack of recognition and the impacts to which Gjoa Haven’s testimonies speak. The method of testimonial reading, as such, deliberately prevents engaging with Gjoa Haven’s experiences without also asking questions about responsibility between speaker and listener. Not only does this make it possible to redirect from writing a “damage-centred” narrative that speaks “for” the community of Gjoa Haven, towards one that draws attention to the colonial legacies and structures that have caused those impacts- it also provides direction for other academic “listeners” to accept testimony of Gjoa Haven’s experiences in appropriate ways.

The knowledge outputs shared here have emerged from the ongoing conversations and agreements between the Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and BW scientists, as described above. You can choose to directly engage with any of them on this page, or you can click the links below to trace the collaborative processes that have lead to each of those final outputs.

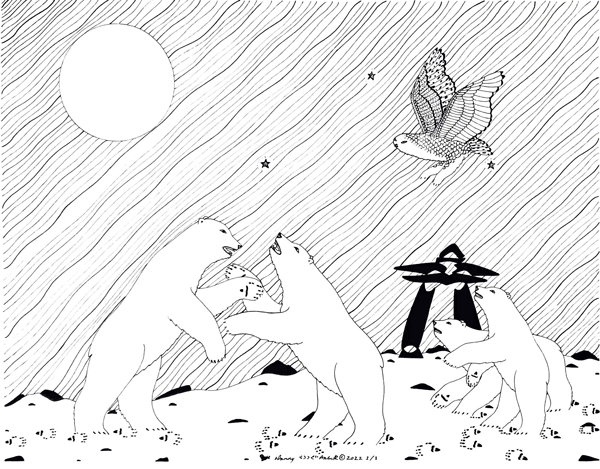

Voices of Thunder Animated Graphic Documentary

"Voices of Thunder" is a community-created, animated graphic documentary, in which Inuit hunters and elders from the community of Gjoa Haven share how they have been impacted by polar bear management policies in their region over the past two decades.

This animated graphic documentary resulted from workshops conducted in Gjoa Haven over the summer of 2019. In these workshops, Gjoa Haven hunters, elders and a number of individuals from outside of the community shared their experiences on the impacts of severe polar bear quota reductions, implemented between 2001 and 2015 in the Polar Bear Management Unit of M’Clintock Channel (MC) with each other and with several scientists of the Genome Canada BearWatch project. After these workshops, a narrative script was co-created by the BearWatch scientists, Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and several community members, that brought together interpreted quotes from the workshops, with archival materials and academic publications.

The choice to add documentation on polar bear quota setting in the MC PBMU, from for example NWMB archives, academic literature, newspaper articles and grey literature like government reports and proceedings was agreed upon by the HTA and BW research partners during one of our conversations in the summer of 2021. Together with the quotes his material was arranged along a narrative timeline, despite the absence of such a temporal context of quota impacts by the hunters and elders in the workshops. We agreed during the process of co-production to strategically present the quotes from the workshops in those ways for two reasons; First, presenting the testimonies as such makes it clearer how Gjoa Haven’s experiences are linked to scientific and political developments and structures over time. This is especially relevant for audiences that might not be familiar with the detailed historical context of quota setting in the MC management unit and associated impacts on Gjoa Haven hunters. Second, the archival documentation draws attention to regulatory, and potentially oppressive structures that have contributed to the experienced shared in the workshop, rather than decontextualizing these experiences from the relationships of power within which they are entangled.

The experiences that are shared in this documentary come from 28 different voices that are narrated as 'we' in this documentary. The narration of these voices happens through the recorded voice of one speaker from the community, while the archival documentation that provides particularized institutional context is narrated by another speaker from the community. To provide transparency on the multitude that is embedded within this ‘we’, we have added all the community members that contributed to the narrative by name at the end of the video. You can trace the considerations over this- and other choices that were made during the production of “Voices of Thunder”, here.

Voices of Thunder Synopsis:

"Voices of Thunder" is a community-created, animated graphic documentary, in which Inuit hunters and elders from the community of Gjoa Haven share how they have been impacted by polar bear management policies in their region over the past two decades.

Polar bear management policies in the last two decades, including a polar bear hunting moratorium, have disproportionately impacted Gjoa Haven compared to other Nunavut communities. For two generations they have hardly been able to practice their tradition of hunting polar bears, as a result of international pressures and exclusionary scientific monitoring surveys. Gjoa Haven hunters argue that science could better integrate the knowledge of Inuit themselves and seek recognition for the loss of income, cultural-, and intergenerational knowledge transfer. They want their stories to finally come out - They want their voices of thunder to echo everywhere.

This film was scripted, recorded, drawn and directed by the community members of Gjoa Haven themselves, assisted by a PhD researcher, none of them are professional filmmakers. The video was produced as part of a Genome Canada polar bear research project; BearWatch.

Voices of Thunder Inuktitut Syllabics version

Voices of Thunder English version

Winds of Change Webpage

This webpage was built, based on the ongoing conversations between BW researchers and the Gjoa Haven HTA. As representatives for the larger community, the board had expressed a desire to have their “voices of thunder echo everywhere”. To help them do so, we built this “Winds of Change” webpage; as an online advocacy tool and reference source for Gjoa Haven’s “Voices of Thunder”. Published in English (below) and Inuktitut, including a Syllabics version, it brings together different material resources that have emerged around the creative collaboration between BW scientists and the Gjoa Haven HTA. Some of these outputs, in particular an interactive timeline, available both in Inuktitut- including a syllabic version- and English, function as a reference source for the Voices of Thunder Animated Graphic Documentary and the community’s appeal for recognition. Other content on the webpage facilitate insights on the culturally embeddedness of Gjoa Haven’s appeals, with the lands and the way in which people keep polar bear related practices alive. Either through sharing memories, stories and extended insights on human/polar bear relationships, or by remembering family histories and great hunters of the past through drumdancing and Pihhiq’s (ancestral songs). The page contains video recordings in which several community members share such memories and stories.

Winds of Change Webpage ENG by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada's BearWatch

Voices of Thunder Interactive slideshow

During the co-production of the animated graphic documentary, it became clear that in addition to an academic publication, webpage and video production, a third way of presenting the experiences as shared by Gjoa Haven’s community members, might be desirable. A document that would provide all the same information, arts and experiences that were shared in the animated graphic documentary- but could also afford for responsive interaction with this content.. A supplemental form of output to the video and webpage, was created in the form of an interactive text-based document, available in three versions; English (below), Inuktitut, and Inuktitut syllabics. It was added to the Winds of Change webpage.

English version slideshow

Voices of Thunder interactive slideshow ENG by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada BearWatch

Inuktitut version slideshow

Voices of Thunder interactive slideshow Inuktitut by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada BearWatch

Inuktitut Syllabics version slideshow

Voices of Thunder interactive slideshow Syllabics by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada BearWatch

Voices of Thunder testimonial reading

This section invites you to conduct a testimonial reading of Gjoa Haven’s testimonies. The invite consists of a guided reading, in which you as a reader are encouraged to follow alongside non-Indigenous researchers of the Bearwatch project, and: i) Acknowledge initial affective responses towards selected testimonies; ii) Explore how one may be implicated and, if appropriate, can make oneself accountable as part of a research legacy that has neglected to properly recognize and engage with Inuit knowledge; iii) Explore how one’s field of research contributes to an environment of uneven expectations, and; iv) Work to practice better crosscultural accountability as an academic working with Indigenous partners.

This section is explicitly written from the perspective of the academic partners of the BearWatch project, in response to Gjoa Haven’s testimonies, which are in this section presented through selected slides of the co-created “Voices of Thunder” slideshow. Depending on your own positionality, field of expertise, and the particularities of your research collaborations, this invitation may resonate differentially across readers. Readers that practice community-based wildlife monitoring in the Canadian Arctic will likely find some familiarities across their own research contexts and the context within which the particularities of Gjoa Haven’s experiences have played out. Indigenous readers, on the other hand, may not have much to gain by conducting a testimonial reading alongside non-Indigenous researchers, and would perhaps prefer to engage with Gjoa Haven’s testimonies directly. We recognize the particularities of this testimonial reading, and suggest readers selectively engage with this section to the degree that is fitting with one’s positionality.

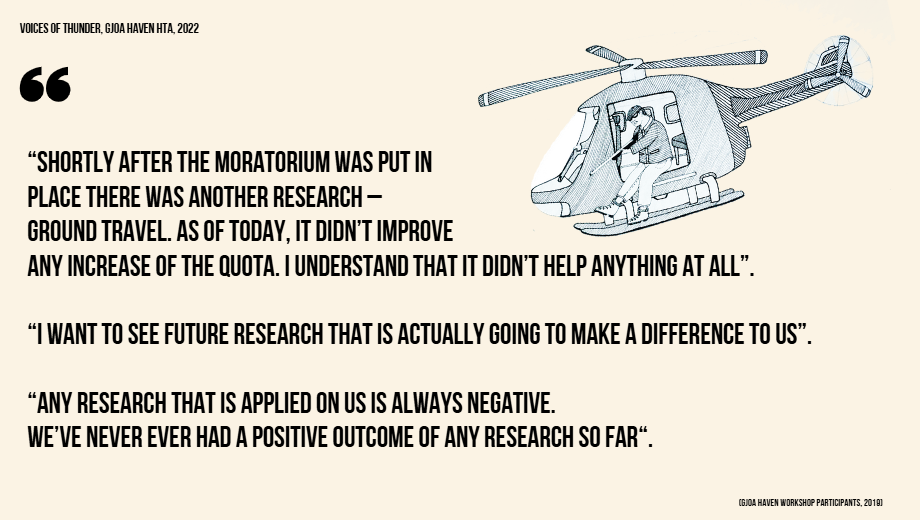

Affective responses

It is not hard to imagine ourselves, as researchers, to be implicated with the experiences shared by community members from Gjoa Haven. The scientific community is in certain cases even directly addressed by workshop participants. Below (figure 6) we share three individual quotes that we have selected from the larger transcript of the 2019 workshops, to provide insights in the ways in which many community members considered scientific research to be entangled with their experiences around quota setting.

These expressed critiques towards the processes and outcomes of research over the past decades, provoked a range of affective reactions among the non-Indigenous researchers of the Bearwatch project. Affect relates here to the emotional and attitudinal engagement with the subject matter, as contrasted with the cognitive domain, which refers to knowledge and intellectual skills related to the material (Seel, 2012). Among such initial affective responses were dissociation, defensiveness, and resistance. V.C. De Groot, for example, being immersed in a relationship with the community of Gjoa Haven to a degree not shared by the other academic members of the collective, took such negative perceptions of research to reflect directly on his personal research history with Gjoa Haven. In response, he pointed out how he has repeatedly reminded the members of the Gjoa Haven HTA throughout their respective collaborations that expectations of outcomes resulting in an upward revision of quota were not going to be met in the shorter term by their shared work. One of the opportunities that a testimonial reading offers us, is to acknowledge the role of emotions and explore how they reflect the stakes at play when we conceptualize ourselves as implicated subjects.

De Wildt, Whitelaw and Lougheed did not perceive Gjoa Haven’s critique of research outcomes as directed towards V.C de Groot’s work per se. Rather they saw such comments as expressing frustration with research practices in general, extending beyond projects related to polar bears - and as a critique of the GN, in particular towards their surveys leading to Gjoa Haven’s near moratorium, and their subsequent lack of timely accountability towards the community. The initial affective response from those three academic partners ranged from defensiveness about the legitimacy of scientific research, a fear of losing community support, and guilt or cognitive dissonance between (violent) historical research practices, and on our current research practices and collaboration.

Such initial affective responses are often left unmentioned in academic publications in favour of more cognitive or rational responses. As a result, many academics do not know how to examine and articulate their feelings towards their own work (Daly, 2005). This can perpetuate oppression, as unexamined emotions like guilt, might lead to denial, or defensiveness that prevent us from studying how affective responses influence practices and choices made within research. Conducting a testimonial reading can assist us in acknowledging the unsettlement that our affective responses clearly speak to. However, rather than letting it trap us into passive feelings of guilt, or lure us towards a ‘settler-colonial horizon of closure’, testimonial readings allow us to acknowledge, and explore such unsettlement more meaningfully - for example through an ethics of responsibility . Guilt forms a trap of one remaining oriented on the past, whereas the assumption of responsibility allows us to be future-oriented by questioning how historical contributions relate to present conditions. ‘’One has responsibility always now’’ (Young, 2010, p.108-9). To transcend passive empathy, we must explore self-implication, and our potentials for taking action- while acknowledging our affective responses (including those of guilt and unsettlement), and allow them to assist us in this process, rather than hold us back.

Invitation: Trail off towards reading about vulnerability