Ethical Space of Engagement

You have found a vista. A vista is a site from which a particular view or prospect is offered. Vistas can quite literally offer a horizon to assist in your navigation, like the outline of rock formations and shorelines would do within Inuit Nunangat. In the case of my knowledge-land-scape, they offer “visions”, mental images that may serve as guidelines to set out and adjust your course during the journey to come.

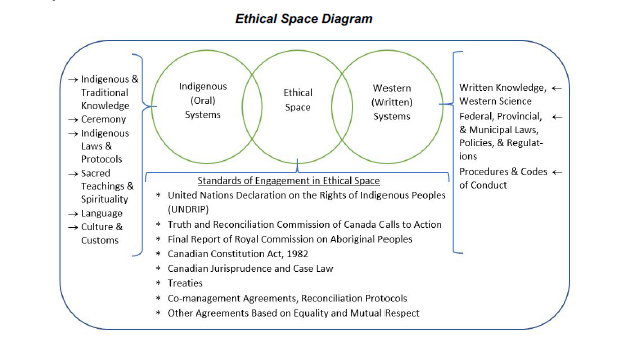

In this particular case, you are presented with the guiding principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE), as proposed by Sturgeon Lake First Nation elder Willie Ermine (Ermine 2007). The ESE, is a “third space” approach, through which differentiated nations or collectives might negotiate ethical encounters with each other in an ‘ethical’ space that belongs to neither. This third space emerges both through principled practices (like for example negotiating terms of engagement), and as a guiding model for willing partners to re-position themselves in-equitable-encounter (Ermine, 2007; Ermine 2015; Indigenous Circle of Experts 2018). When taking the ESE as a guiding frame, ethics are no longer a pre-emptive box to tick nor a static end-goal. Ethical research is rather performed as a dynamic state of becoming which requires ongoing negotiation and decolonization.

Figure 1: The Ethical Space Diagram, originally published by the IISAAK OLAM foundation (2019). Re-used with permission.

When looking out over this Vista, you wonder what it means in the thick moment/um of reconciliation to engage with the experiences of Gjoa Haven community members, in accordance with the guiding principles of the Ethical Space of Engagement. In particular you wonder about what kind of practices it takes to enter such an “ethical” space, outside of your own frames of reference. You decide to return to your original path and continue moving across this knowledge-land-scape landscape, while paying extra attention to the things around you

Return to cut 1: Voices of Thunder

Alternatively, you can keep on going. You have heard that researchers of the BearWatch project have already organized some workshops, and they might have made some recordings.

Such accepting testimony, however, isn’t limited to a ‘passive reading’ of the quota impacts on the community. You are hereby instead invited to become a “wayfarer”.

Becoming a wayfarer entails a willingness on your part to become an active and immersed agent in the ongoing material opening and closing of opportunities for meaning-making within my research. As such a role requires response-ability, from your part it is thus also important to formulate the boundaries and benchmarks particular to such a social contract, before you continue. Terms of engagement if you will.

Per definition, this knowledge-land-scape is not the land, nor the ice, or the rocks, seasons and animals with which Inuit and other knowledge holders become knowledgeable and move through the world. The (digitized) materials that de/markate this knowledge-land-scape are rather ethnographic traces like voicenotes, photos, drawings, edited videos, notes, and posters and presentations, as well as academic texts and workshops, that emerged from my fieldwork.

This knowledge-land-scape is explicitly not about providing access. It adheres to Inuit-driven EEE protocol 3 (ICC, 2020), in that it respects cultural “differences”. My work does not somehow make otherwise “remote” regions legible, accessible or available for consumption. Nor does it take the liberty to “represent” the experiences of Gjoa Haven’s community-members, or their knowledge. My knowledge-land-scape is not meant to be taken as a descriptive representation, but instead more of an emergent event. An emergent topology that materializes responsively in-between subject-object, reader-author and land-scape.

Not everything is furthermore possible within this knowledge-land-scape. The platform as a whole is not meant to sketch a comprehensive and complete oversight of the institutional or socio-political land-scape of community-based polar bear management. It rather prioritizes the particular, intra-dependent, and partial perspectives over a ‘god trick’, in which one claims to see, but remains oneself unseen (Haraway, 1988 p.581). If a reader would want to explore the whole knowledge-land-scape, for example, they would likely have to re-visit it multiple times. Such partiality also, explicitly, refers to the platform itself. The boundaries and possibilities of the platform are de/markated by how my own aesthetic actions in the field have diffracted with other agents, including the research apparatus of western science, at play in the field of polar bear monitoring research. Although the knowledge-land-scape thus indeed materializes for the reader based on their own choices, the possibilities and conditions for these choices are nevertheless still bounded by my decisive cuts as a researcher.