Wayfaring the BearWatch Project

Point of Beginning

Abstract

Introductie

Polar bears have captured the public imagination for being charismatic and as one of the most politicized animals in the world (e.g. Strode 2017; Slocum 2004). There is little disagreement across cultures regarding polar bears as a species of importance, whether as a keystone predator, a sentinel of changing Arctic environments, a cultural icon, as a more-than-human relative, or a source of income through the guiding of sports hunts. The reconciliation of such differences within polar bear management is, on the other hand, less straightforward. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ, the Inuit way of knowing and being in the world) considers humans and bears, for example, to co-exist in a relationship that requires harmonic balance for it to remain ongoing (see for example Keith 2005; Karetak et al. 2017), while western formulations of wildlife conservation conceptualise polar bears, on the other hand, as a species in need of management to ensure its survival. The importance of reconciling such seemingly opposite ways in which polar bears matter across cultures, has increasingly been recognized, and even formalised through Territorial Land Claims Agreements across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit Homelands, see ITK, 2018).

The polar bear co-management regime in the Nunavut Settlement Area for example, is based on the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement (NLCA), which states that ‘Inuit must always take part in decisions on wildlife’ (NTI 2004), while ‘the guiding principles and concepts of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) are to be described and made an integral part of the management of wildlife and habitat’ (Wildlife Act 2003). Despite such formalised co-management, tensions remain. Significant data-gaps, and the international pressures to fill such gaps, as well as a rapidly changing Arctic environment and the difficulties of conciliating vastly different ways of knowing and being in wildlife conservation continue to haunt in particular the management and monitoring of polar bears in Inuit Nunangat.

This cut focusses in particular on the challenge of conciliating western sciences and IQ in community-based polar bear monitoring. More precisely, it asks the question of what it means within the larger apparatus of community-based polar bear research to practise knowledge conciliation under guidance of the principles of the ethical space of engagement, rather than by data-driven needs. I ask this question as a non-Indigenous PhD researcher as part of a larger project that’s called ‘Bearwatch: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge’ – hereafter referred to as ‘Bearwatch’. Bearwatch ran between 2015 and 2023, during which it sought to meaningfully engage IQ in its development of a new non-invasive genomic polar bear monitoring toolkit. The project was a collaboration between northern communities in the Nunavut Settlement Region and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, HTAs in Gjoa Haven and Coral Harbor, the Inuvialuit Game Council, the governments of Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon, the Canadian Rangers, and researchers and students from multiple universities across Canada. Most researchers and policymakers in the field of polar bear science more generally- and on the Bearwatch project more particularly- are either western-educated scientists from a variety of natural sciences, or Inuit knowledge- and rights holders. I, myself, am a white, queer, settler-guest researcher from the Netherlands with a background in the arts and social sciences. Approaching this research context as a non-Indigenous researcher from such a different cultural and disciplinary place of beginning than the other Bearwatch team members and most people in the field, has added another layer of complexity to the already challenging issue of ethical knowledge-relating across cultures. I have aimed to leverage this intra-cultural complexity to seek additional disciplinary ways of understanding- and possibly practising- knowledge conciliation, in accordance with the guiding principles of ‘the Ethical Space of Engagement’ (Ermine, 2007), within the western science-heavy field of polar bear monitoring.

I explore whether it’s possible to rethink the challenges of ethical reconciliation between IQ and data-driven western science in polar bear monitoring through an arts-based, post-disciplinary practice-based approach. As will become clear in the following pages, I don’t attempt to formulate a “new-”, “alternative”, or “innovative” problem-solving approach to knowledge conciliation across cultural differences. Instead, I perform a particular positioning and ongoing opening-, through a practice of wayfaring (as forwarded by Ingold, 2010) that’s guided by the concept of ‘ethical space’ (as forwarded by Ermine 2007).

This ethical space, as I will explain later, emerges both through principled practices and as a condition for (non-)Indigenous sciences and knowledge systems to re-position themselves as more equitable partners-in-encounter. In this cut, I invite you along with my own post-disciplinary art-based research, to experience how the principles of ethical space have helped me reposition myself within the BearWatch project. This cut also provides possibilities to gain insights on how these principles have guided me in my attempts to practice my methodological wayfaring in respectful dialogue with IQ and western natural sciences. This cut does not so much manifest in a list of conclusive take-aways, but rather seeks to provide the conditions for you as a reader to find your own way and gain emergent insights on what it means to ethically encounter and engage.

Invitation(s)

Throughout this knowledge-land-scape, and thus also along this cut, I invite readers to become an intra-dependent agent of meaning making, and as such an implicated part of my research. My writing and research-creations function as an extended site of encounter across reader, author and the more-than-human intra-active agents, practices and events that were part of my fieldwork in the hamlets of Uqsuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven) and Salliq (Coral Harbour) of the respective Kitikmeot- and Kivalliq region in the territory of Nunavut. This extended site of encounter allows readers the possibility to respond-. In other words, it draws on the reader's abilities and willingness to ethically, and responsibly engage with some of the diffractive possibilities as they were encountered by me during my research within the BearWatch project. To facilitate possibilities for such intra-active response, I have extended multiple invites to trail-off from each main cut. The purpose of such possible wandering is to facilitate engagement across the multiple sites of encounter in which my research has taken place, through the possibilities of wayfaring, as put forward by Tim Ingold (2010).

Wayfaring

Ingold (2010) describes the wayfarer as ‘a being who, in following a path of life, negotiates or improvises a passage as he goes along’ (Ingold, 2010 s126). Wayfaring is a body-on-the ground, material way of knowing that emerges along the course of everyday activities, rather than built up, gathered or collected from ‘fixed locations’. Rooted in the ‘weather-world’ of complex entanglements and partial perspectives, it drives the research along as a process that is unfixed, fluid and in constant motion of coming to know-, or becoming -other. As a transcultural, methodological practice, I argue that a process of wayfaring allows for ethical knowledge conciliation to be understood as a space, practice and process of engagement, that can take place in correspondence with the Ermine’s ethical Space of Engagement (ESE, 2007)- instead of as a data-driven endeavour. Knowledge can be seen as ongoing, fluid and place-based, rather than frozen in time, packageable and exportable. It makes it possible to attune to the seasons and make meaning through navigating both the physical, relational and the institutional landscape through an ethics of care and attention.

In its simplest form, wayfaring is a practice of responding, correspondence, and of practicing one’s own response-ability. Relying on such response-ability in this knowledge-land-scape is the difference between an open-ended, future-oriented practice of collective sense-making, and a dead-end, unidirectional trajectory of me guiding you towards a description of best research practices in accordance with publicly available Inuit guidelines on ethical engagement, like for example those of the ICC’s ‘circumpolar Inuit protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement’ (2022) or the National Inuit Strategy on Research (ITK, 2018). This proposition is not in any way meant to discredit such guidelines. It rather points out that such guidelines will not be very effective if they are not being responded to or enacted with gestures of meaningful intent.

The publication of such guidelines can perhaps be, in following with Ingold, compared to the lines of an architectural drawing. Such lines are a descriptive gesture, an instruction. What we get to read in the publication of such guidelines, is the final result of a creative process; an instructive product about protocols, rather than insights of the productive process that has brought these protocols themselves into being. In other words, the 2022 ICC publication can be understood as a trace of agreements about ethical engagement, rather than as an active practicing of ethical engagement itself. It is hard to be in lively correspondence with a trace – beyond, of course, the act of narrowly following it to its final destination. Such a trace tells a story, but it is itself not story-ing: it doesn’t move, change or respond in relation to your engagement with it. For such lively intra-action, correspondence, or relational resonance, one needs to consider guidelines on ethical practices as a multi-directional verb. Not a retro-spective trace-ing, but rather for example a prospective thread-ing (Ingold, 2020 p.181).

The difference between the trace and the thread as an intentional practice of moving through the world is directional. The trace is both retro- and/or prospective, it describes a one-sided story of a past or future event. The thread, perhaps as a ball of yarn -as Ingold asks us to think about it- is on the other hand, neither retro- nor prospective. It is emergent, and winds or unwinds as you proceed through the world with it (Ingold 2020). This emergent quality of continuously opening up to the world is what makes the thread alive and respondent. To wayfare as a thread, is not so much about moving forward, or towards something, but is rather about transformation. A movement in which nothing remains static; nature- and the researcher included -become emergent; being necessarily turns into becoming, and representing turns into performing ongoing movement. This is what navigating the knowledge/land/scape affords. It allows for you, as a reader to engage, return, and be in correspondence with my research. It is an ongoing process of re-positioning.

Wayfaring the BearWatch project

The explorative goal of this cut is therefore, not so much to argue for a specific outcome or practice of knowledge relating, but rather to deepen our understanding of how, as researchers operating with(in) the traditions and institutes of western science, we can practice ethical research under open-ended conditions of uncertainty. In pursuit of such a goal, I have moved away from presenting solutions, towards facilitating a process of becoming.

This cut performs certain key-moments of the BearWatch project that took place during the period that I was part of the project, as possible sites of encounter and ethical engagement. You are invited to follow along the unfolding of the project through these key moments. They are performed as sites of diffractive im/possibilities between narrative vignettes, ethical dilemmas, research-creations, and auto-ethnographic fieldnotes that emerged from my own practice-based engagements within the communities of Gjoa Haven and Coral Harbour. Along the way in-between such sites you are either re-directed by the material forces of emergent ice-pressure ridges (a land-based metaphor for the more-than-human agencies that intra-act to shape the conditions under which some of this work has taken place), or invited to trail-off on unexpected side-tracks (which perform the possibility of wandering). Such redirections provide possibilities to orient or gain emergent insights on what it means within this particular research context to practice polar bear research as an ethical space, or process of engagement.

Deriving value from this work requires immersion and attentiveness. Such is the futurity that this dissertation aims to enable and contribute to; extended ethical knowledge encounters between Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge holders, multidisciplinary research teams, and academic readership, based on ethical and attentive engagement. Remaining a distanced spectator will not do. As such, this cut starts by taking you along to a series of workshops that were conducted in Gjoa Haven, during the Summer of 2019.

Workshops Summer 2019

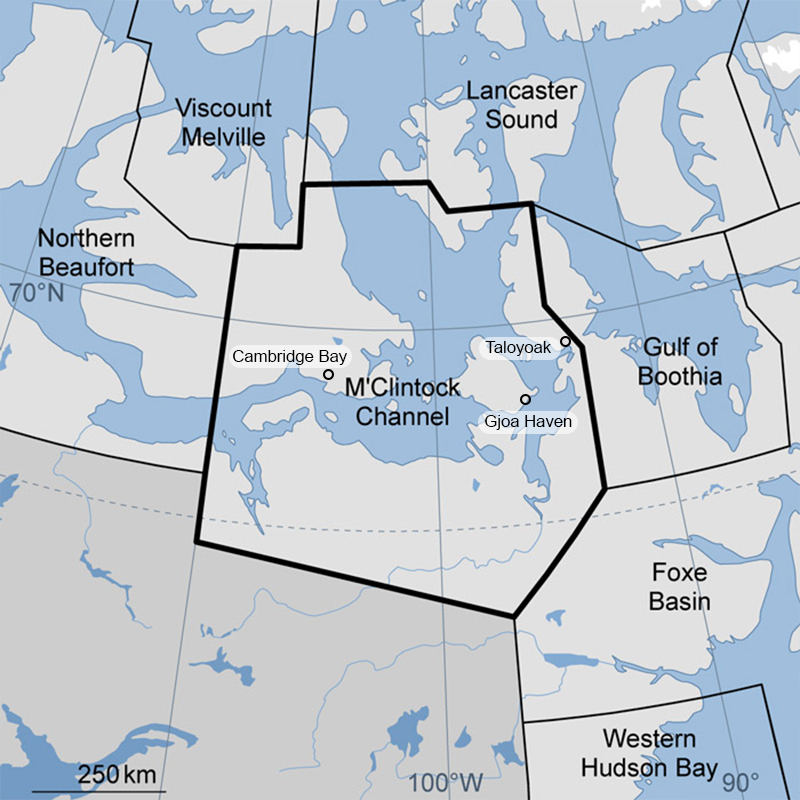

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Based on a desire for recognition and acknowledgement of the impact of these polar bear quota regulations, two workshops were co-organized, in the summer of 2019, to discuss and document testimonies of Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members.

The workshops were advertised over the radio in both English and Inuktitut (Inuit language), and interested individuals signed up through the HTA. One workshop was held May 15, 2019 in the evening with 10 participants and one on May 16 in the morning with 11 participants. These participants comprised mainly older male community members, many of whom had hunted, or still hunt polar bears. There were two female participants in each workshop. Three of the participants were between the ages of 20 and 40, with the remainder older. The two workshops focused specifically on the impacts of polar bear hunting quota reductions on the community. The workshop questions were co-designed by the BW academic researchers and HTA representatives and were asked in both English and Inuktitut to prompt discussion. The format however remained open-ended, meaning that "off-script" discussions were encouraged during the workshop, and occasionally specific members were asked to participate in answering particular questions because of their connection to the issue, as identified in previous interviews or by other community members. Two BW researchers and an interpreter would ask the pre-designed questions and prompt discussion, while a third BW researcher made notes. Both workshops were audio-recorded.

These recordings and workshop notes became the primary materials which were transferred to me, as a new PhD student on the BW project in 2020, with the purpose of having these experiences written out and shared with a larger academic audience, through academic publishing, as part of the overarching research project. This purpose however presented me with multiple dilemmas;

Stay with the trouble and engage with the "politics of recognition"

Coral Harbour First trip 2020

Invitation:Join along for a Caribou hunt

Covid-19

Explore deeper: Personal whereabouts during Covid-19

Covid-19 Remote interviews

Fieldtrip BW team Summer 2021

Coral Harbour

Driving the Island

Drinking Coffee

Gjoa Haven

HTA meetings presentations

Voices of thunder meetings

Stranding the car

ATV ride

Camping at the Weir

Invitation:Trail-off to understand better how my whereabouts influenced my writing, reading and broader relationship to the country after this fieldtrip

Meetings Spring 2022 Gjoa Haven

Checking seal dens

Collecting ice

Meetings Spring 2022 Coral Harbour

Spending time in Yan's Cabin

Qamutiq building and riding

Walking the same road every day

Seasonal changes

Illness

Gender based violence

In text link to Point of Beginning Mx. Science

Fall 2022 Coral Harbour

In text link naar Design consultation pre-workshop & workshop Coral Harbour

remote planning

illness

tension

absence

Wayfaring Calendar pilot

Arctic travel

Fall 2022 Gjoa Haven

In text link naar Design consultation pre-workshop & workshop Gjoa Haven

Preparing cabin pre-workshops

Cooking/ Sharing food

Prayer

Truck Flat Tire

In text return to Preparation Gjoa Haven workshop in the Workshop Gjoa Haven trace.