Point of Beginning Animated Graphic Documentary

This is one of three case studies conducted as part of my research that seeks to explore how ethical knowledge conciliation may come to matter within community-based polar bear research. This particular case case study cuts across the step-by-step practices of community-based film-making. Initially these practices evolved only around the co-creation of an animated motion graphic documentary "Voices of Thunder", however several smaller video projects branched off from this initial film-making.

Film Narrative and Archival Work

The script for "Voices of Thunder" draws directly from the recordings of the workshops in 2019. All the quotes in the film are directly taken from the transcribed interpretations without editing.

The quotes used were selected based on their thematic connection to the topic of polar bear quota - sometimes the conversation at the workshop would venture into related issues, like quota regulations of other animals. Such diverging comments, along with comments that would repeat previous points without adding new information were omitted from the script.

To place the quoted experiences within a contextual narrative, we added documentation of the processes around polar bear quota setting in the MC management unit. This also led to the choice of arranging the interpreted quotes along a linear timeline, despite the absence of such a temporal presentation of quota impacts by the hunters and elders in the workshops.

We nevertheless collectively agreed during the process of co-production to strategically present our narratives in this way for two reasons; First, presenting the testimonies as such makes it clearer how Gjoa Haven’s experiences are linked to scientific and political developments and structures over time. This is especially relevant for audiences that might not be familiar with-, but are nevertheless interested in, the detailed historical context of quota setting in the MC management unit and associated impacts on Gjoa Haven hunters.

Second, the archival documentation draws attention to regulatory, and potentially oppressive structures, rather than decontextualizing the experiences from the relationships of power in which they are entangled. By doing so, we don’t only draw explicit attention to the impacts of the severe quota reductions as experienced by Gjoa Haven hunters and community members. We present these experiences, not with a focus on the suffering and pain of the community, but rather by redirecting the gaze towards questing the institutional structures underlying these experiences – actively invoking questions of responsibility and relational accountability.

Storyboarding and Artwork

Once the script was adapted, finalized and approved through a collective reading with the HTO board, we started to visualize scenes through a combination of sketching and conversation. This latter exercise was done with a smaller group; HTO chairman James Qitsualik, vice-chairman William Aglukkaq, Jacob Keanik, me and BearWatch co-PI Peter van Coeverden-de Groot, a total of five people. We first decided which parts of the script felt like they would together comprise a scene. We then discussed how we could best visualize that scene; for example where it would take place, and who would be present? As they would start conversing together and lay out a particular setting -often drawn from situations in their own life, or from other hunters-, I would start sketching multiple rough compositions based on their descriptions without interrupting their conversation. At moments where it felt appropriate, I would present multiple quick sketches, and ask them to select and comment on which composition felt like it best reflected the setting of their description, and or what changes it needed to better reflect their description.

After the selection and adaptation of each sketch I would ask follow-up questions to gain a better understanding of that particular scene. For example, in the opening scene of the film we see two hunters and their dogs hunt a polar bear. More detailed descriptions for this scene clarified that that the hunters should wear traditional garbs, and weapons like a bow and arrow and a spear, because it described a pre-quota moment in time. James and William would clarify how these weapons were used; the spear for example would be used in up close encounters with polar bears and held in place by balancing the spear on one foot. Explanations like these would often result in bringing up memories of their own hunting stories and polar bear encounters, which were also shared with lots of excitement and referrals to specific locations on the map hanging on the wall of the HTO office. Aesthetic experience triggering memories

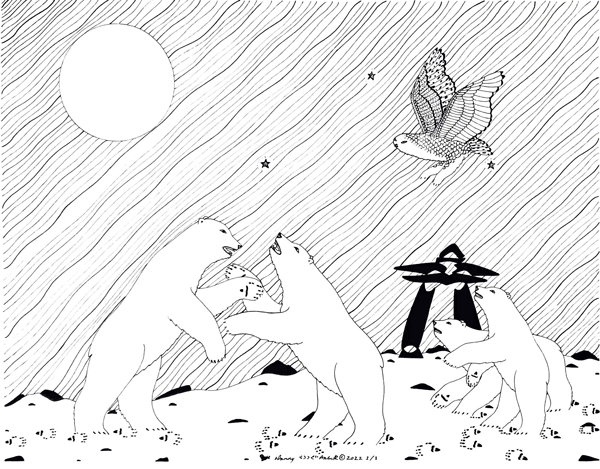

After co-creating a preliminary storyboard in this way, I would take the descriptions, notes and rough sketches to Danny Aaluk; a Gjoa Haven based graphic artist who had been pointed out by the HTO board to work on this film with. Danny makes detailed black and white ink-drawings that he sells to tourists that arrive by cruise ship in the summer, teachers and researchers that come into town. He also makes artwork for local events, the school and the hamlet office, and is occasionally invited to art-fairs in the South.

Danny and I would end up spending a lot of time together. We would talk the scene through, and he would ask detailed questions on the content of each scene. More quick sketches from both me and Danny could often clarify the compositions of each setting and what kind of details were discussed with the HTO board members. Sometimes Danny would ask questions that I could not answer, spurring follow-up conversations with James and William. These conversations sometimes brought up new details for certain scenes. For example, it became clear that the traditional hunting scene should also have dogs in it, because dogs were very important companion animals in the hunting of polar bears. They would go ahead and sometimes even kill the bear before the hunter could catch up. Whenever Danny had finished a drawing I would bring them to James and William, to see if anything was missing or should be changed. Sometimes minor changes were made, like in the scene where the MoU between the NWMB, Gjoa Haven and Cambridge bay is signed.

The drawings often invoked affective responses during which the initial stories and experiences that had led to the drawing were repeated, or more related stories shared.

The process of collaborating with Danny also allowed for an opportunity to get to know each other. Both as creative collaborators, but also on the level of building an informal, personal relationship. We would usually spend considerable amounts of time chatting or drinking tea before and after the more transactional activities of payment, and dropping off drawings or sketches. As is the case with many of the other people in the community that I ended up collaborating with, such moments were also often combined with small favours like rides to the store or elsewhere in town, technical assistance with phone plans or small monetary advances for upcoming work. Very often these moments would also include Danny sharing stories about his grandfather who would take him out on the land and teach him about the animals and the ice. Although these are informal moments, outside of the research agenda and data collection, I argue they cannot be seen as separate from the research. These informal moments of sharing knowledge and mutual care, account for the relations that become a crucial part of community-based research.

Audio Recording and Translation

During the summer of 2021, my accommodation was the, what is referred to in the community of Gjoa Haven, ‘old arcade’ or the ‘blue house’. This blue house functioned as a launch pad for on-the-land sampling activities for multiple research projects due to its size and affordances for storage.

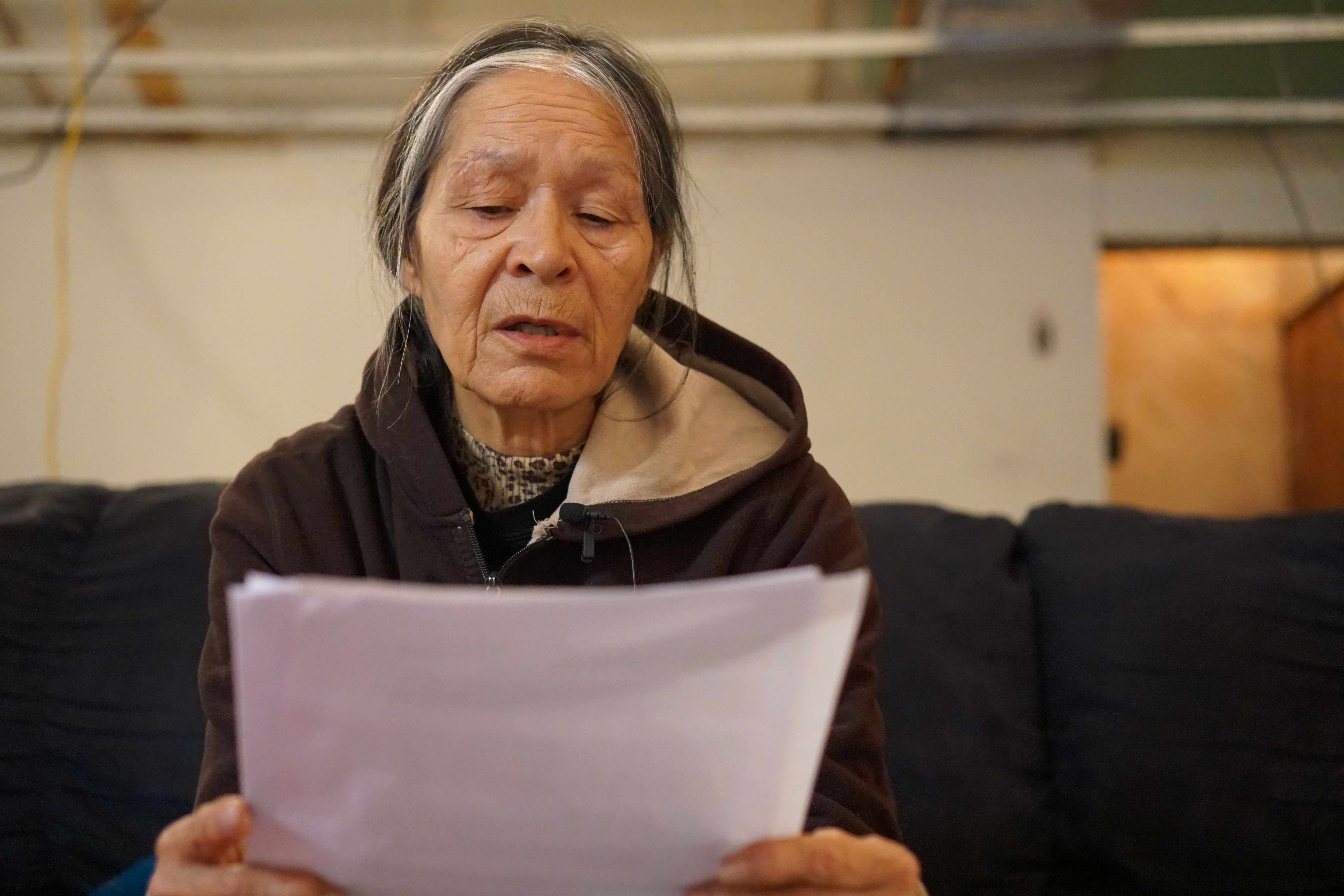

To record the audio tracks for the voices of thunder film we needed a sound-controlled environment. Due to a lack of housing in Nunavut most homes are overcrowded, with very little opportunity for uninterrupted audio-recording. Houses and offices are furthermore often heated by noisy oiltanks, which posed an additional challenge to record clean audio. The blue house, mentioned above, eventually turned out to afford a quiet space for recording through the possibility of turning of the heating and other electrical equipment. Although this was effective, it was not very comfortable. We would be able to record 20 minutes and then turn the heat back up, as to not get too cold.

Editing and Motion Graphics

After spending five weeks in the community of Gjoa Haven, I had collected a lot of audio-visual material to create multiple formats of creative media around Gjoa Haven's "Voices of Thunder". Moreover, the process of filmmaking, storyboarding, recording voice-overs, co-facilitating storytelling workshops and undertaking many other activities- both central, and tangentially related to film-making- in the community, had given me an possibility to enter into relationship with multiple community members that I would have otherwise likely not have met. Many of the people I worked with, fell outside of the usual network that was engaged around polar bear research in the past, and many of the people I connected with were women.

For the subsequent 6 months, I worked with this material to edit three versions of the Voices of Thunder documentary, and create a throatsinging and Pihhiq video. I also create an interactive timeline and website that allowed for people to engage with Gjoa Haven's testimonies in other formats than film.

In particular the process of turning Danny Aaluk's drawings into motion graphics, and the adding of subtitles to each video, required an intimate engagement with both the voice-over recordings and Danny's drawings. In fact, I can still hear Tuppittia's voice echoeing in my head, almost two years after finalizing the films. Spending time with the material over and over again gives a sensitivity to language. In this case, it invoked questions on how language works in relation to the land. From the perspective of someone who does not speak Inuktitut, there seemed relatively little variation in intonation and tone, either in the voice-overs and the singing of the pihhiq. Nevertheless, I was told multiple times that the words used "paint a picture of the land".

Landmark: Song, Dance and Oral Storytelling"

Collective Film Screenings GH

In the spring of 2022 I returned to Gjoa Haven by myself. I was welcomed "home" immediately, as many people had remembered seeing me around town the previous year. This visit allowed me to screen an intermediate version of the Voices of Thunder documentary for the Gjoa Haven HTA and co-create some missing material for the final edit with Danny Aaluk, who I had collaborated closely with during my previous visit.

I was also able to screen the two other videos with all the people that had participated in making them. After the screening we shared bannock, pop and soup, prepared by Danny Aaluk's mother, and had a collective discussion on the cultural meaning of the songs and dances that the people had performed in the videos.

Or, take a small detour to Cut 1, if you would like to see the final creative research outputs of Gjoa Haven's "Voices of Thunder" - you will be able to return to this cut.

Take a detour to cut 2: Point of Beginning (Pre-)workshops, to move on to the next case study of aesthetic action: The final BearWatch workshops conducted in Gjoa haven and Coral Harbour.