The ESE (process)

You have found a vista. A vista is a site from which a particular view or prospect is offered. Vistas can quite literally offer a horizon to assist in your navigation, like the outline of rock formations and shorelines would do within Inuit Nunangat. In the case of my knowledge-land-scape, they offer “visions”, mental images that may serve as guidelines to set out and adjust your course during the journey to come.

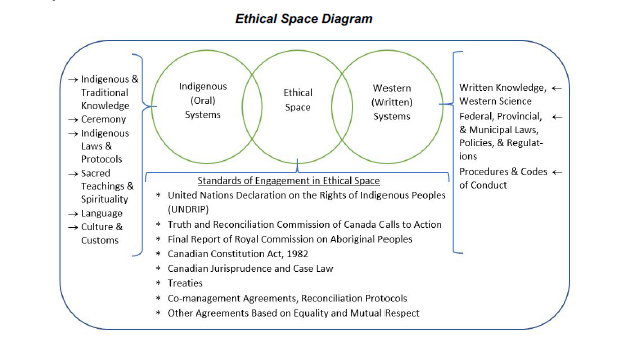

In this particular case, you are presented with the guiding principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE), as proposed by Sturgeon Lake First Nation elder Willie Ermine (Ermine 2007). The ESE, is a “third space” approach, through which differentiated nations or collectives might negotiate ethical encounters with each other in an ‘ethical’ space that belongs to neither. This third space emerges both through principled practices (like for example negotiating terms of engagement), and as a guiding model for willing partners to re-position themselves in-equitable-encounter (Ermine, 2007; Ermine 2015; Indigenous Circle of Experts 2018). When taking the ESE as a guiding frame, ethics are no longer a pre-emptive box to tick nor a static end-goal. Ethical research is rather performed as a dynamic practice of encountering which requires ongoing negotiation.

Figure 1: The Ethical Space Diagram, originally published by the IISAAK OLAM foundation (2019). Re-used with permission.