Voices of Thunder

Point of beginning

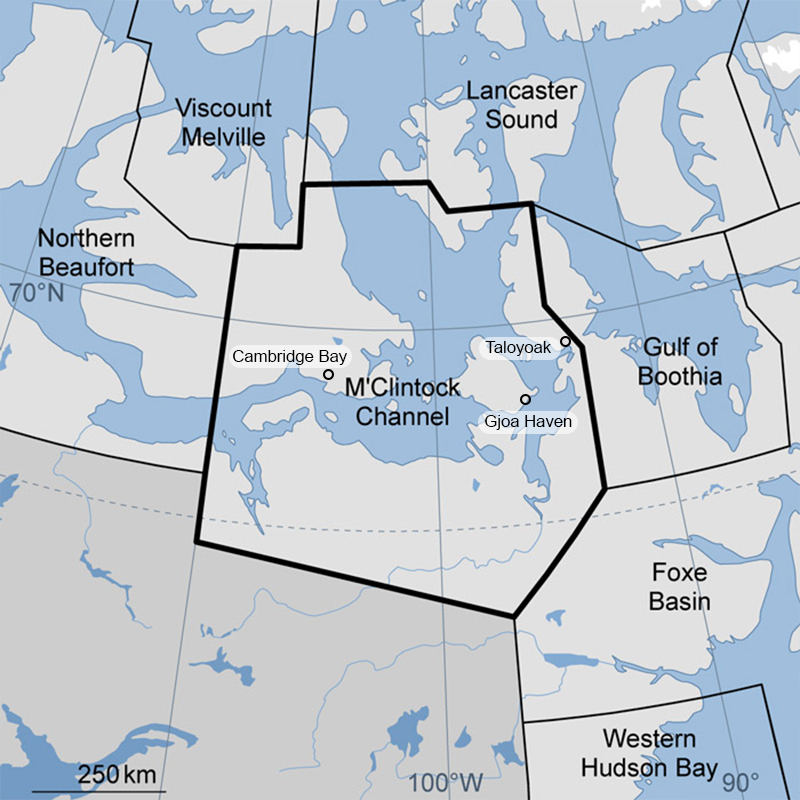

This manuscript/cut and its related work emerges from five years of ongoing conversations between representatives of the Gjoa Haven’s Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut (figure 1) and Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario researchers. It is based on a series of community-based workshops conducted in the summer of 2019 for a ‘Genome Canada’ sponsored large-scale polar bear monitoring project entitled “BEARWATCH: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge” – hereafter, simply, BW.

Several Inuit communities across Inuit Nunangat (homeland of Inuit of Canada’, ITK, 2018) have collaborated with the BW project to combine Inuit Knowledge with western science in developing a community-based, non-invasive, genomics-based toolkit for the monitoring and management of polar bears. One of these collaborating communities is Gjoa Haven, whose Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) representatives have a research relationship with BW co-PI Peter Van Coeverden De Groot that has stretched across more than 20 years. Over the years, one issue that was brought up repeatedly by Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and other community members, concerned the effects of severe polar bear hunting quota reductions introduced to the community in 2001.

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. Both Taloyoak and Cambridge Bay- unlike the residents of Gjoa Haven- however, also have traditional hunting grounds outside of the MC PBMU. So, when the quota in MC PBMU was significantly reduced from an average of 33 bears annually before 2000 (US FWS, 2001), to only 3 bears annually (NWMB, 2005), the community of Gjoa Haven was disproportionately impacted. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Hunting polar bears is an important part of Inuit culture. It facilitates inter-generational knowledge transmission of on-the-land skills, and provides a significant source of income within Inuit mixed-economies (Dowsley, 2008; Wenzel, 2011). After two generations of hardly being able to hunt polar bears, Gjoa Haven hunters still seek recognition for the impacts such quota-decisions have had in terms of lost income, loss of culture, and loss of intergenerational knowledge transfer.

This work invites you to accept testimony to these ongoing impacts of such severe quota reductions through the recorded experiences of Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. Such accepting testimony, however, isn’t limited to a ‘passive reading’ of the quota impacts on the community. You are instead invited to explore your own positioning- as a reader, a scientist, and collaborative meaning-maker responsively, alongside several other agential forces. What does it mean to ethically engage with these narratives? What responsibilities do we bear as readers? How are we implicated? What does it mean in the thick moment/um of reconciliation to share or accept testimony in accordance with the guiding principles of the Ethical Space of Engagement (Ermine, 2007)?

Text will be added here - see google doc

From purveying voices towards accepting testimony.

In the summer of 2019, two workshops were co-organized to discuss and document testimonies on the multiple impacts of the polar bear quota reductions on Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. The recordings of these workshops and its accompanying notes became the primary materials which were transferred to me, as a new PhD student on the BW project in 2020, to be described in an academic publication, and presented to a larger academic audience.

As a researcher who had not yet set foot in the community of Gjoa Haven, such an "assignment" made me feel uneasy; Who was I to write an academic paper that conveyed the lived experiences of people who I had never even met? Viewing the writing on such a sensitive topic as polar quota reductions, as a mere descriptive practice- disconnected from the wider research landscape within which they emerged- did not only strike me as unethical, it also seemed impossible. It is hard to separate the practices of a research project that is directly focussed on the methodologies of polar bear monitoring, from the subject of harvest quota- considering that quotas are set, at least partially, based on the insights derived from such monitoring efforts. As such it seemed particularly important to proceed with caution and with a sensitivity to how the BW project, and its non-Inuit researchers, are entangled within the larger legacy of scientific polar bear monitoring surveys and management processes that resulted in the impacts as shared in the workshop.