Chores Around Town: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

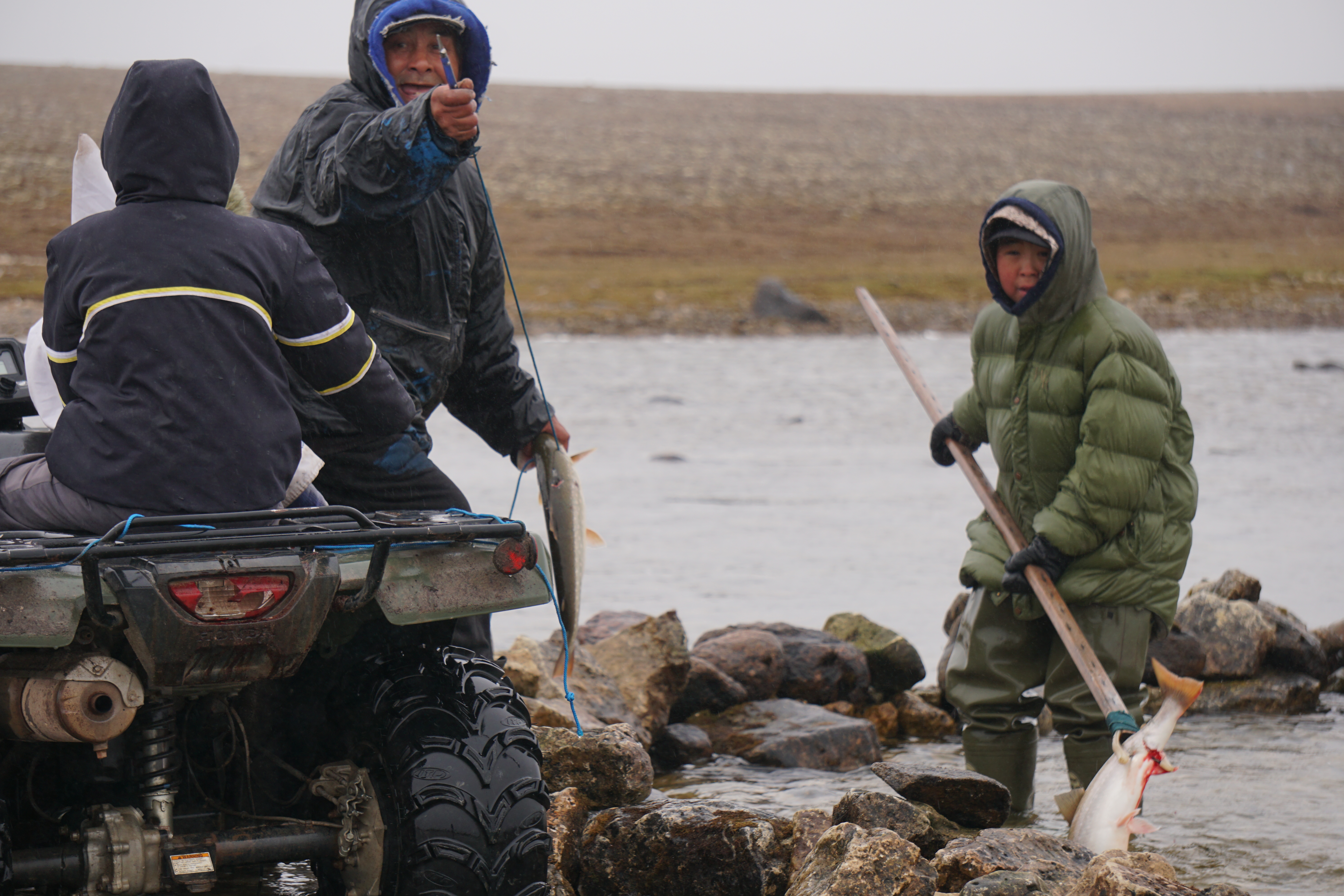

Being present in the community has taken many shapes for me over the course of my multiple field visits. In Gjoa Haven such presence has often taken shape around activities that are part of Inuit day to day life. In the first week, when BearWatch researchers were present in Gjoa Haven in larger numbers, we for example helped George Konana take out his nets. | Being present in the community has taken many shapes for me over the course of my multiple field visits. In Gjoa Haven such presence has often taken shape around activities that are part of Inuit day to day life. | ||

In the first week, when BearWatch researchers were present in Gjoa Haven in larger numbers, we for example helped George Konana take out his nets. | |||

[[File:DSC00145.jpg|thumb]] | [[File:DSC00145.jpg|thumb]] | ||

| Line 8: | Line 10: | ||

=Stranding the Car= | =Stranding the Car= | ||

Most possibilities to get involved with chores around town and meeting people involved | Most possibilities to get involved with chores around town and meeting people involved an old truck, the elements, and project-related logistics that had me drive across town for multiple purposes. | ||

These activities created both possibilities and limitations in terms of community interaction patterns. | |||

For example, the collective efforts required to pull the truck out of the ocean, when it stranded on the beach and got flooded by the rising tide of the ocean, is part of what co-Pi de Groot terms his “vulnerability narrative”. A performative display of intra-dependency he understands his relationship with the community at large to be comprised of. | |||

[[File:DSC00312.jpg|thumb]] | [[File:DSC00312.jpg|thumb|Truck stranded in the ocean (photograph by author.)]] | ||

=Preparing and Packing for an ATV Ride= | =Preparing and Packing for an ATV Ride= | ||

Revision as of 11:53, 1 March 2025

Being present in the community has taken many shapes for me over the course of my multiple field visits. In Gjoa Haven such presence has often taken shape around activities that are part of Inuit day to day life.

In the first week, when BearWatch researchers were present in Gjoa Haven in larger numbers, we for example helped George Konana take out his nets.

Stranding the Car

Most possibilities to get involved with chores around town and meeting people involved an old truck, the elements, and project-related logistics that had me drive across town for multiple purposes.

These activities created both possibilities and limitations in terms of community interaction patterns.

For example, the collective efforts required to pull the truck out of the ocean, when it stranded on the beach and got flooded by the rising tide of the ocean, is part of what co-Pi de Groot terms his “vulnerability narrative”. A performative display of intra-dependency he understands his relationship with the community at large to be comprised of.

Preparing and Packing for an ATV Ride

The environmental conditions in Inuit Nunangat seem initially a fitting context to easily debunk anthropocentric ontologies. For example, any visiting researcher who has tried to prepare, pack or pull a qamutiq (sled) across the land outside of Arctic Summer for the first time, like I did in 2021, has likely encountered the limits of human agency as well as the particular teachings of humility. Fumbling around with thick mitts, pens and paper, while knots need to be tied, and qamutiks need to be repaired, for example quickly eliminates the feasibility of (ethnographic) documenting on-the-spot. What remains, however, is attentive presence.

Camping at the Weir

After 4 hours of travelling by ATV, some of it in the dark, we arrive at the fishing Weir. After setting up the tents we watch George and his family spearfishing for a while.