The Great White Beast: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Landmark.png|thumb]] | [[File:Landmark.png|thumb]] | ||

What | How do we determine who is a scientist? How do we meet each other in "scientific" spaces? What are the markers of inclusion, where lie the boundaries, and how do we recognize each other? | ||

The | At the Annual Science Meeting in Toronto in December 2022, I was not often immediately recognized as a researcher or a scientist. Some attendees thought I was a performing some kind of mythical creature. Other associated me with the "smurfs". The lack of determinable signifiers prompted explorative questions like: are you wearing a costume? Is this a mask? Others were more explicit with their uncertainty: "I feel like I am walking into a minefield, how do I refer to you? Are you a persona? A character? I haven't kept up...", as if my presence was meant to perform a test of their use of language. | ||

For others, there was some relief, when they could mark me as an "insider" through my official conference nametag (One side displayed my name and institutional affiliation in print, the other side displayed "Mx. Science in my own handwriting). Such marking as an "insider", was often immediately followed up with questions of my underlying research, my methodology or "what" my presence was supposed to represent. When the request for a re-presentative answer, or clear underlying message about science or scientists, remained unaccommodated, the moment of relief was replaced with various degrees of discomfort. | |||

Explaining that Mx. Science becomes meaningful within encounters like the one we were engaging in then sparked for many a curiosity to explore - a trajectory that was often engaged through the form of a follow-up interview after the conference. Each of these interviews was semi-structured around three questions, how did Mx. Science affect you? Do you think Mx. Science was representative of something? What do you think Mx. Science was practicing at the conference? The ensuing conversations indicated that Mx. Science performed a very different material-discursive practice for each person that engaged with them. Whether this practice related to how we engage with the "other" during our research, how we take up space in settler-Indigenous context, or what (unexamined) standards of representability we uphold in scientific spaces. | |||

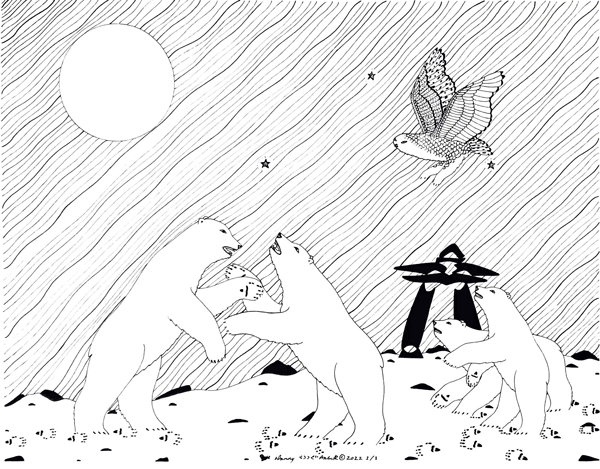

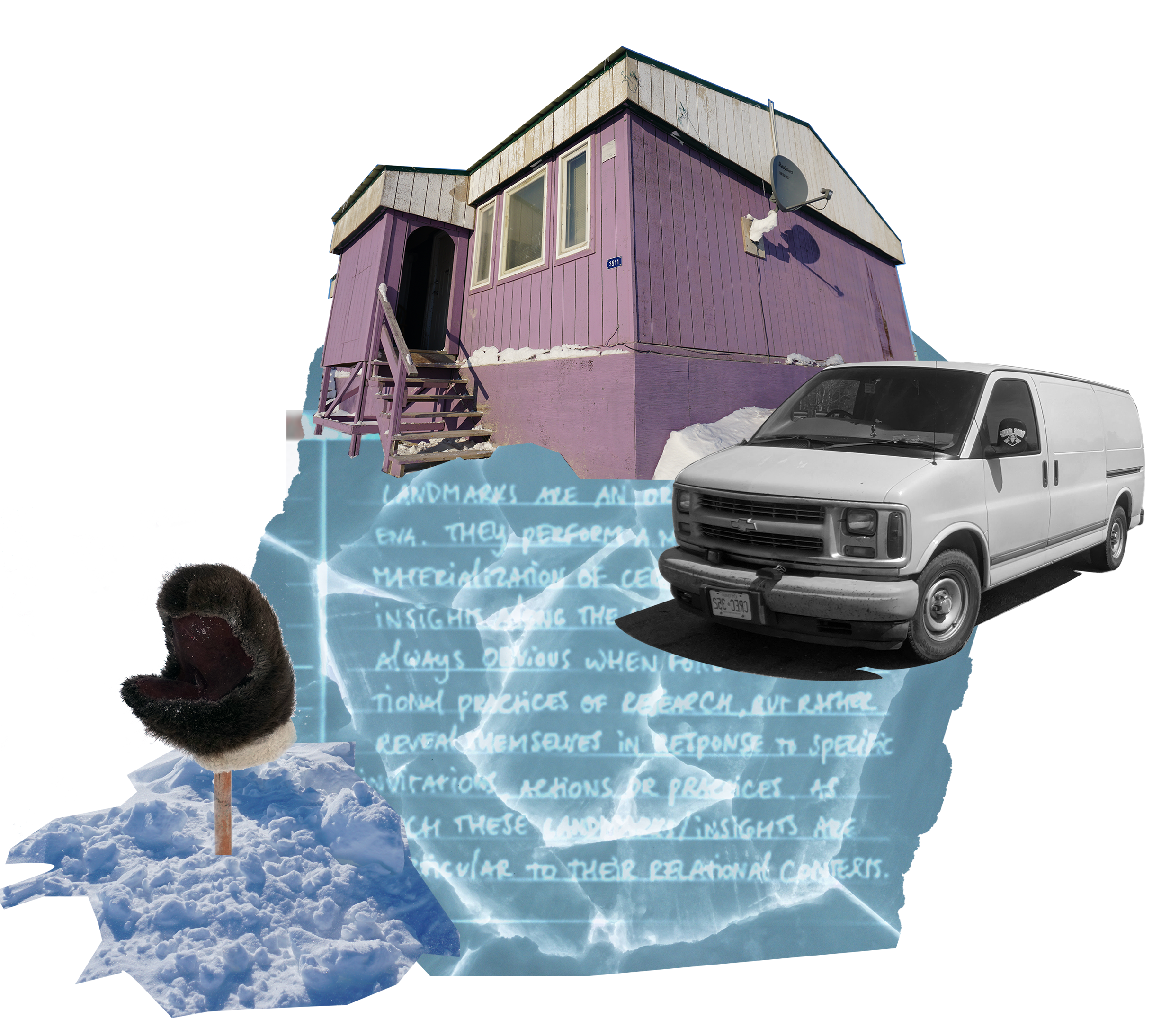

Mx. Science is thus a liminal figure that conjures many shapeshifting, associative frames, depending on who encounters them. Such an idea may potentially be put into dialogue with traditional Inuit beliefs and legends of the polar bear, who is traditionally referred to as the "Great White Beast" (Jimmy Qirqut, Gjoa Haven Elder, 2022) and is also a shapeshifting figure. Sometimes human, sometimes bear. | |||

Although some resonance can be found between Mx. Science and Inuit legends of shapeshifting polar bears, I am more interested in the resonance between Mx. Science and the Great White Beast of settler-colonialism, while simultaneously evoking a frame of powers and agencies that extend beyond our own comprehension or capacities: a “beast of a problem”. | |||

<span class="return to-cut-2 link" data-page-title="Point of Beginning Mx. Science" data-section-id="5" data-encounter-type="return">[[Point of Beginning Mx. Science#The Liminal and the Ethical Space|Return to Cut 2: "Mx. Science"]]</span></span> | <span class="return to-cut-2 link" data-page-title="Point of Beginning Mx. Science" data-section-id="5" data-encounter-type="return">[[Point of Beginning Mx. Science#The Liminal and the Ethical Space|Return to Cut 2: "Mx. Science"]]</span></span> | ||

Revision as of 20:05, 9 February 2025

How do we determine who is a scientist? How do we meet each other in "scientific" spaces? What are the markers of inclusion, where lie the boundaries, and how do we recognize each other?

At the Annual Science Meeting in Toronto in December 2022, I was not often immediately recognized as a researcher or a scientist. Some attendees thought I was a performing some kind of mythical creature. Other associated me with the "smurfs". The lack of determinable signifiers prompted explorative questions like: are you wearing a costume? Is this a mask? Others were more explicit with their uncertainty: "I feel like I am walking into a minefield, how do I refer to you? Are you a persona? A character? I haven't kept up...", as if my presence was meant to perform a test of their use of language.

For others, there was some relief, when they could mark me as an "insider" through my official conference nametag (One side displayed my name and institutional affiliation in print, the other side displayed "Mx. Science in my own handwriting). Such marking as an "insider", was often immediately followed up with questions of my underlying research, my methodology or "what" my presence was supposed to represent. When the request for a re-presentative answer, or clear underlying message about science or scientists, remained unaccommodated, the moment of relief was replaced with various degrees of discomfort.

Explaining that Mx. Science becomes meaningful within encounters like the one we were engaging in then sparked for many a curiosity to explore - a trajectory that was often engaged through the form of a follow-up interview after the conference. Each of these interviews was semi-structured around three questions, how did Mx. Science affect you? Do you think Mx. Science was representative of something? What do you think Mx. Science was practicing at the conference? The ensuing conversations indicated that Mx. Science performed a very different material-discursive practice for each person that engaged with them. Whether this practice related to how we engage with the "other" during our research, how we take up space in settler-Indigenous context, or what (unexamined) standards of representability we uphold in scientific spaces.

Mx. Science is thus a liminal figure that conjures many shapeshifting, associative frames, depending on who encounters them. Such an idea may potentially be put into dialogue with traditional Inuit beliefs and legends of the polar bear, who is traditionally referred to as the "Great White Beast" (Jimmy Qirqut, Gjoa Haven Elder, 2022) and is also a shapeshifting figure. Sometimes human, sometimes bear.

Although some resonance can be found between Mx. Science and Inuit legends of shapeshifting polar bears, I am more interested in the resonance between Mx. Science and the Great White Beast of settler-colonialism, while simultaneously evoking a frame of powers and agencies that extend beyond our own comprehension or capacities: a “beast of a problem”.