Knowledge as Movement and Dwelling: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

As a figure in this Knowledge-Land-Scape, "Landmarks" perform the materialization of certain findings and emergent insights along the way. | As a figure in this Knowledge-Land-Scape, "Landmarks" perform the materialization of certain findings and emergent insights along the way. | ||

This particular one, marks my understanding of how some knowledge only comes into being through movement- or only | This particular one, marks my understanding of how some knowledge only comes into being through movement- or may only exist ''as'' movement. | ||

"Becoming nomadic" , the notion of transience and of "passing", as Rosi Braidotti refers to such ways of knowing, binds us to multiple others in a web of complex interrelations, kinship, social bonding and flexible citizenship (Braidotti, 2006). This is not knowledge that can be learnt from a book, nor is it knowledge that can be categorized or transferred for shared understanding outside of its relational events (Ingold, 2022). as the kind that can shared | |||

Link to EEE protocol. | Link to EEE protocol. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 16: | ||

<div class="next_choice"> | <div class="next_choice"> | ||

Then return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder, or Cut 3: Wayfaring the Bearwatch project</span> | Then return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder, or Cut 3: Wayfaring the Bearwatch project</span> | ||

Revision as of 13:14, 26 January 2025

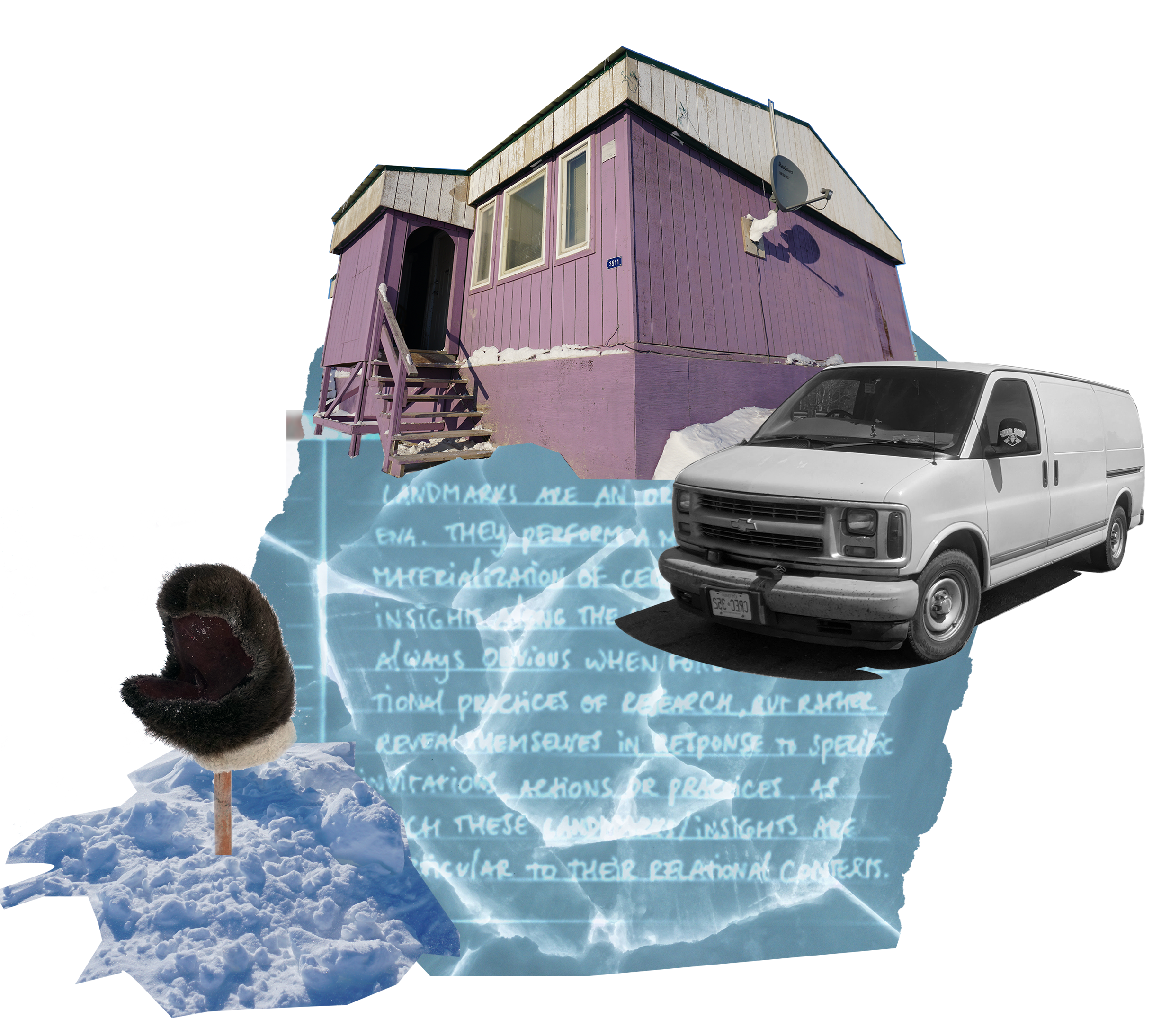

Landmarks are defining features in the land that traditionally play an important role in Inuit topographical understandings of their land and its resources. They are important orienting features to keep one's bearing while travelling and to determine where one is located at any given moment[1].

As a figure in this Knowledge-Land-Scape, "Landmarks" perform the materialization of certain findings and emergent insights along the way.

This particular one, marks my understanding of how some knowledge only comes into being through movement- or may only exist as movement.

"Becoming nomadic" , the notion of transience and of "passing", as Rosi Braidotti refers to such ways of knowing, binds us to multiple others in a web of complex interrelations, kinship, social bonding and flexible citizenship (Braidotti, 2006). This is not knowledge that can be learnt from a book, nor is it knowledge that can be categorized or transferred for shared understanding outside of its relational events (Ingold, 2022). as the kind that can shared

Link to EEE protocol.

Grasping the possible existence of a third space in-between requires thinking about difference without falling into the trap of binary, essentialist approaches similar to those that position western and Indigenous knowledges against each other in a false dichotomy (see Agrawal, 2002). To engage this concept of in-betweenness in a meaningful way, is thus by necessity a philosophical endeavour that leads us away from the ontological certainties provided by Cartesian divides.

In-betweenness allows for intra-relational thinking across entities and events, rather than inter-relational thinking merely between entities and events. This difference lies in movement, is spurred on by practice- and by extent challenges the persistent split between knowing and being in hegemonic western. sciences.

Then return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder, or Cut 3: Wayfaring the Bearwatch project

Cut 3: Wayfaring the BearWatch Project

- ↑ Aporta, C. (2004). Routes, trails and tracks: Trail breaking among the Inuit of Igloolik. Études/Inuit/Studies, 28(2), 9-38.