Wayfaring the BearWatch Project: Difference between revisions

m Saskia moved page Wayfaring the BW project Point of Beginning to Wayfaring the BearWatch Project: Misspelled title |

|

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 15:35, 15 January 2025

The land invites one to move away from anthropocentric tellings - towards narrations of becoming knowledgeable in company with the seasons, snow, ice, wind, lichens, caribou and many more. Such stories leave room for us as researchers, but aren’t about us.

Acknowledgements

An explicit note of acknowledgement for this cut goes out in particular to George Konana, in Gjoa Haven, and Leonard Netser in Coral Harbour. Both men have taken me out on the land, the sea and the ice on multiple occasions between 2020-2023. They patiently took time to introduce me to their land and explained how they found their way in various ways and under multiple conditions. Although they graciously responded to my many questions, I am most grateful to their valuable lessons of guiding me to tag along and just be present for the ride.

Becoming a Wayfarer

My name is Saskia de Wildt. This cut, focusses on my Phd research on the challenge of conciliating western sciences and IQ in community-based polar bear monitoring research. More precisely, it traces my processes as I asks the question of what it means to practice knowledge conciliation under guidance of the principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE, Ermine, 2007) and the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement (EEE, 2020) rather than based on data-driven needs.

Knowledge Conciliation in Polar Bear Research

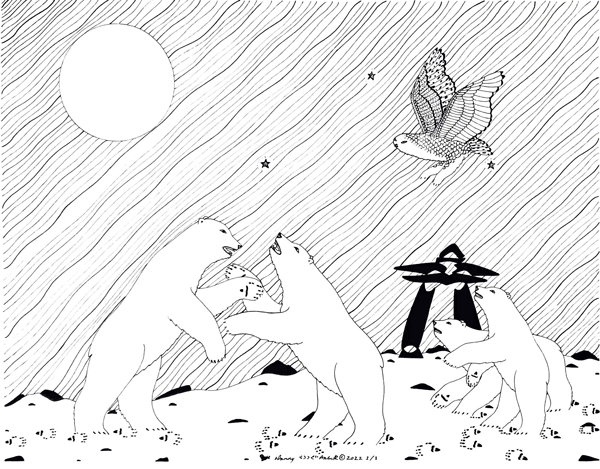

There is little disagreement regarding polar bears as a species of importance - whether as a keystone predator, a sentinel of changing Arctic environments, a source of sustaining more-than-human relations, or as sources of income through guided sports hunts. The reconciliation of such differences of valuing and knowing polar bears within polar bear management is, on the other hand, less straightforward. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ, the Inuit way of knowing and being in the world, or “that what Inuit have always known to be true”) considers humans and polar bears, for example, as traditionally co-existing in a relationship of larger land-based entanglements that requires harmony and balance. Western formulations of wildlife conservation, on the other hand, typically, conceptualize polar bears as a species in need of human intervention to ensure their survival. The importance of reconciling such seemingly opposite ways in which human/bear relationships matter, has increasingly been recognized in Canada.

This is partly the result of the efforts of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC), amongst which their reconciliatory principles and their 94 Calls to Action. It is, however, arguably more directly the result of Inuit trailblazing efforts to formalize Territorial Land Claims Agreements in wildlife co-management systems across Inuit Nunangat: the Inuit homelands, the preferred term for specifically, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nunavik (Northern Québec) and Nunatsiavut (Northern Labrador) in Canada).

The polar bear co-management regime in the Nunavut Settlement Area, for example, is based on the 1993 Nunavut Land Claim Agreement (NLCA), that states that “Inuit must always take part in decisions on wildlife”, while “the guiding principles and concepts of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) are to be described and made an integral part of the management of wildlife and habitat.” Despite such formalized co-management, tensions remain. Data-driven conservation, management and monitoring of polar bears in Inuit Nunangat, while necessary to address significant data gaps on population trends and a rapidly changing Arctic environment, has also proven itself a challenging environment for the conciliation of different ways of knowing and being.

Wayfaring as a Sensitizing Method

Knowledge conciliation in polar bear monitoring matters. Hunting polar bears is an important part of Inuit culture. It facilitates inter-generational knowledge transmission of on-the-land skills, and provides a significant source of income within Inuit mixed-economies (Dowsley, 2008; Wenzel, 2011). Getting the management quota ‘’right’’ is thus not so much only a question of ensuring Inuit rights, and sustainable harvest of polar bear populations, it’s also a question of Inuit day-to-day safety, relational harmony in line with IQ, and ensuring ongoing access to the land.

My wayfaring approach, as will become clear, does not attempt to formulate a new, alternative, or innovative means of knowledge conciliation across cultural differences, nor does it lead to conclusive take-aways about ethical knowledge conciliation. It instead unsettles fixed ideas about “knowledge” towards a “coming to know”, and instead of “knowledge integration” it performs the idea of “worldly encounters”.

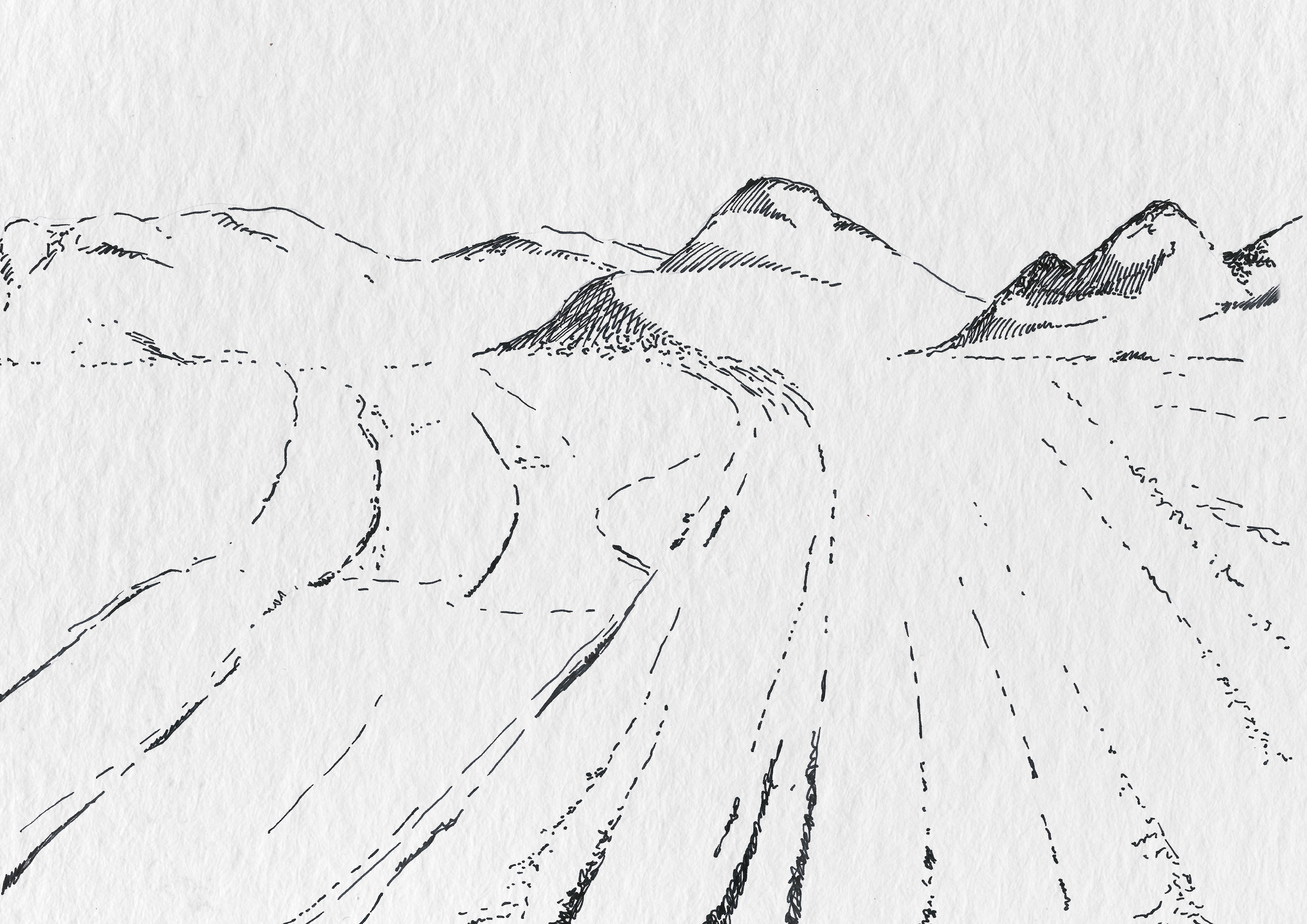

The wind leaves snowdrifts in particular directions across the land, and ripples across the surface of the water. Traditional trade routes, and seasonal tracks cut lines throughout the land, in the direction of specific landmarks or places with abundant wildlife – even if they are only visible to the trained eye or during certain seasons. Marine currents create pressure ridges, cracks and gaps, depending on the direction the currents push the ice above them. These cuts and movements draw new lines across the region, and intra-act with others; sometimes redirecting, and other times creating other, new patterns for the remainder of the season. Each of these lines emerges, responds and intra-acts as one with each other. The lines we draw and the traces we leave in the environment differ, depending on the nature of our movements. The knowledge that is accumulated along such lines, in turn, also differs.

The BearWatch Project

Bearwatch ran between 2015 and 2023, during which it sought to meaningfully engage IQ in its development of a new non-invasive genomic polar bear monitoring toolkit. The project was a collaboration between northern communities in the Nunavut Settlement Region and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, HTAs in Gjoa Haven and Coral Harbor, the Inuvialuit Game Council, the governments of Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon, the Canadian Rangers, and researchers and students from multiple universities across Canada and beyond.

Most researchers and policymakers in the field of polar bear science more generally – and on the BearWatch project particularly – are trained in a variety of natural science disciplines of the western academic institute, or they are Inuit knowledge and rights holders. I, myself, am a white, queer, settler-guest researcher from the Netherlands with a background in the applied arts and social sciences, which has required me to negotiate and navigate my own way of meaning making alongside many of the project’s activities.

Decision-making

You now have a choice to make. Will you trace the most straightforward path across the BearWatch project, engaging mostly with the project reports of BearWatch? Or will you start threading your own intra-dependent way alongside the project and me?

Otherwise, it might be helpful to look up the meaning of “intra” dependency, as opposed to “interdependency” before you keep going.

If you choose to keep following this cut instead, you will jump straight into the BearWatch project- beginning with the TEK workshops that were held in the community of Gjoa Haven in 2019 as to inform a feasibility study on future community-driven polar bear fecal sample collection.Detour: look up the meaning of "intra-dependency"

TEK Workshops

The BearWatch project was designed to include a “Genomics and its Environmental, Economic, Ethical, Legal and Social aspects (GE3LS)” component (BearWatch research proposal, 2016 p.30-31).

Three TEK mapping workshops were co-designed with the HTA of Gjoa Haven, as part of this GE3Ls strategy to ‘identify TEK gaps’ and ‘fill them’. The temporal and spatial polar bear TEK that was collected, was processed and published by Scott Arlidge, who also participated in the project. The TEK that was collected ‘provides a georeferenced knowledge base that displays information on polar bears including harvest sites, bear movement, denning sites, and hunter knowledge areas’ (Arlidge, 2022 p.13). This knowledge is shared in his thesis as i) ‘a historical record of polar bear knowledge for the community of Gjoa Haven’; and ii) ‘as a guide to areas of high polar bear activity for future targeted polar bear monitoring effort’s’ (Arlidge, 2022 p.ii).

Keep going to attend the impacts workshop. Or,

Detour, to continue your research on GE3LS. Or,

Go check out the "Knowledge Co-production" WrecksiteWrecksite: Knowledge Co-production

Workshops Summer 2019

The impacts workshops were advertised over the radio in both English and Inuktitut (Inuit language), and interested individuals signed up through the HTA. One workshop was held May 15, 2019 in the evening with 10 participants and one on May 16 in the morning with 11 participants. These participants comprised mainly older male community members, many of whom had hunted, or still hunt polar bears. There were two female participants in each workshop. Three of the participants were between the ages of 20 and 40, with the remainder older. These two workshops focused specifically on the impacts of polar bear hunting quota reductions on the community. The workshop questions were co-designed by the BW academic researchers and HTA representatives and were asked in both English and Inuktitut to prompt discussion. The format however remained open-ended, meaning that "off-script" discussions were encouraged during the workshop, and occasionally specific members were asked to participate in answering particular questions because of their connection to the issue, as identified in previous interviews or by other community members. Two BW researchers and an interpreter would ask the pre-designed questions and prompt discussion, while a third BW researcher made notes. Both workshops were audio-recorded.

What to do?

If you choose to not engage further with the community of Gjoa Haven for now, "Keep going" to trace cut 3: the unfolding of the BearWatch project, and prepare for your first fieldtrip to Coral Harbour. Or,

Stay with the trouble and explore in what ways the “Politics of recognition” complicates such writing practices.Stay with the Trouble: The Politics of Recognition

Coral Harbour First Trip 2020

Alongside funding from Genome Canada, the project PI’s also successfully applied to the Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada/ World Wildlife Fund to fund ‘traditional knowledge research and a denning survey in Coral Harbour, Nunavut’ (Schedule H, 2020, March 31. This intended study included documenting polar bear TEK in Coral Harbour, surveys of vacated dens by locals to collect a variety of samples and data, and the initiation of a collaborative effort with the high school to train students in land-based surveys.

Covid-19

The den survey and TEK collection activities in Coral Harbour were planned for March and April, but were postponed due to COVID-19. The Hamlet of Coral Harbour requested outside visitors stay away the day before most of the BearWatch team was set to arrive in the Hamlet, and the BearWatch PI’s respected their wishes. I had, however, travelled North a day early, and arrived in the community on exactly the day that the Covid-19 epidemic was declared pandemic. Non-resident travel bans came into effect in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories immediately, while physical distancing requirements within communities were put in place a little later.