Wayfaring the BearWatch Project: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

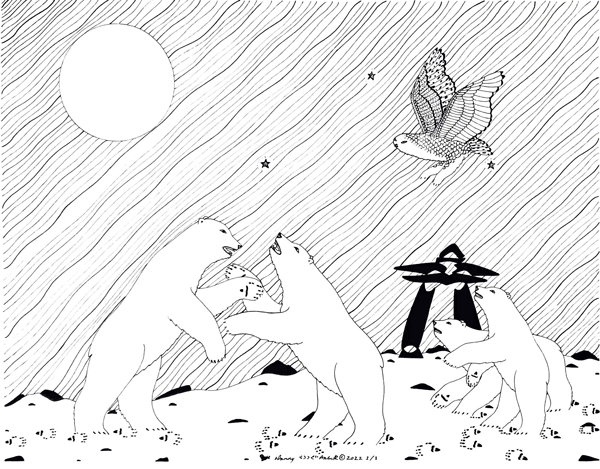

The land invites one to move away from anthropocentric tellings - towards narrations of becoming knowledgeable in company with the seasons, snow, ice, wind, lichens, and caribou. Such stories leave room for us as researchers, but aren’t about us. (or better quote, Ingold, Ermine or EEE) | The land invites one to move away from anthropocentric tellings - towards narrations of becoming knowledgeable in company with the seasons, snow, ice, wind, lichens, and caribou. Such stories leave room for us as researchers, but aren’t about us. (or better quote, Ingold, Ermine or EEE) | ||

Media | |||

<small>Acknowledgements | <small>Acknowledgements | ||

| Line 10: | Line 9: | ||

=Becoming a Wayfarer= | =Becoming a Wayfarer= | ||

This cut, focusses on the challenge of conciliating western sciences and IQ in community-based polar bear monitoring research. More precisely, it asks the question of what it means to practice knowledge conciliation under guidance of the principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE), as proposed by Sturgeon Lake, Ontario, Canada First Nation elder Willie Ermine, and the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement (EEE) rather than based on data-driven needs. | This cut, focusses on the challenge of conciliating western sciences and IQ in community-based polar bear monitoring research. More precisely, it asks the question of what it means to practice knowledge conciliation under guidance of the principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE), as proposed by Sturgeon Lake, Ontario, Canada First Nation elder Willie Ermine, and the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement (EEE) rather than based on data-driven needs. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 16: | ||

=Terms of engagement= | =Terms of engagement= | ||

Polar bears have captured the public imagination for being charismatic and as one of the most politicized animals in the world (e.g. Strode 2017; Slocum 2004). There is little disagreement across cultures regarding polar bears as a species of importance, whether as a keystone predator, a sentinel of changing Arctic environments, a cultural icon, as a more-than-human relative, or a source of income through the guiding of sports hunts. The reconciliation of such differences within polar bear management is, on the other hand, less straightforward. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ, the Inuit way of knowing and being in the world) considers humans and bears, for example, to co-exist in a relationship that requires harmonic balance for it to remain ongoing (see for example Keith 2005; Karetak et al. 2017), while western formulations of wildlife conservation conceptualise polar bears, on the other hand, as a species in need of management to ensure its survival. The importance of reconciling such seemingly opposite ways in which polar bears matter across cultures, has increasingly been recognized, and even formalised through Territorial Land Claims Agreements across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit Homelands, see ITK, 2018). | Polar bears have captured the public imagination for being charismatic and as one of the most politicized animals in the world (e.g. Strode 2017; Slocum 2004). There is little disagreement across cultures regarding polar bears as a species of importance, whether as a keystone predator, a sentinel of changing Arctic environments, a cultural icon, as a more-than-human relative, or a source of income through the guiding of sports hunts. The reconciliation of such differences within polar bear management is, on the other hand, less straightforward. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ, the Inuit way of knowing and being in the world) considers humans and bears, for example, to co-exist in a relationship that requires harmonic balance for it to remain ongoing (see for example Keith 2005; Karetak et al. 2017), while western formulations of wildlife conservation conceptualise polar bears, on the other hand, as a species in need of management to ensure its survival. The importance of reconciling such seemingly opposite ways in which polar bears matter across cultures, has increasingly been recognized, and even formalised through Territorial Land Claims Agreements across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit Homelands, see ITK, 2018). | ||

Revision as of 20:11, 12 January 2025

The land invites one to move away from anthropocentric tellings - towards narrations of becoming knowledgeable in company with the seasons, snow, ice, wind, lichens, and caribou. Such stories leave room for us as researchers, but aren’t about us. (or better quote, Ingold, Ermine or EEE)

Media

Acknowledgements

An explicit note of acknowledgement for this cut should go out in particular to George Konana, in Gjoa Haven, and Leonard Netser in Coral Harbour. Both men have taken me out on the land, the sea and the ice on multiple occasions between 2020-2023. They patiently took time to introduce me to their land and explained how they found their way in various ways and under multiple conditions. Although they graciously responded to my many questions, I am most grateful to their valuable lessons of guiding me to tag along and just be present for the ride.

Becoming a Wayfarer

This cut, focusses on the challenge of conciliating western sciences and IQ in community-based polar bear monitoring research. More precisely, it asks the question of what it means to practice knowledge conciliation under guidance of the principles of the ‘Ethical Space of Engagement’ (ESE), as proposed by Sturgeon Lake, Ontario, Canada First Nation elder Willie Ermine, and the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement (EEE) rather than based on data-driven needs.

To engage with such a sensitizing question, entails- as will become clear- multiple shift. A shift of positioning; from distanced observer or reader to becoming an entangled “subject” – and a practical shift from operating based on fixed principles, to a practice of ongoing negotiations and ethical encounter. This shift applies also to you as you make your way through this knowledge-land-scape. Depending on the choices you make, you might shift from being a reader, to becoming a wayfarer.

Terms of engagement

Polar bears have captured the public imagination for being charismatic and as one of the most politicized animals in the world (e.g. Strode 2017; Slocum 2004). There is little disagreement across cultures regarding polar bears as a species of importance, whether as a keystone predator, a sentinel of changing Arctic environments, a cultural icon, as a more-than-human relative, or a source of income through the guiding of sports hunts. The reconciliation of such differences within polar bear management is, on the other hand, less straightforward. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ, the Inuit way of knowing and being in the world) considers humans and bears, for example, to co-exist in a relationship that requires harmonic balance for it to remain ongoing (see for example Keith 2005; Karetak et al. 2017), while western formulations of wildlife conservation conceptualise polar bears, on the other hand, as a species in need of management to ensure its survival. The importance of reconciling such seemingly opposite ways in which polar bears matter across cultures, has increasingly been recognized, and even formalised through Territorial Land Claims Agreements across Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit Homelands, see ITK, 2018).

The polar bear co-management regime in the Nunavut Settlement Area for example, is based on the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement (NLCA), which states that ‘Inuit must always take part in decisions on wildlife’ (NTI 2004), while ‘the guiding principles and concepts of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) are to be described and made an integral part of the management of wildlife and habitat’ (Wildlife Act 2003). Despite such formalised co-management, tensions remain. Significant data-gaps, and the international pressures to fill such gaps, as well as a rapidly changing Arctic environment and the difficulties of conciliating vastly different ways of knowing and being in wildlife conservation continue to haunt in particular the management and monitoring of polar bears in Inuit Nunangat.

To be a wayfarer, in opposition to being a traveller, is to be able to make decisions in-between and along the way. Wayfaring is not about crossing “over” from, or “across” point A to point B. It is about what happens on the way. When such a process is applied to the challenge of cross-cultural knowledge conciliation in line with the principles of the ESE, this also – as will become clear - entails a degree of shared meaning making with others. In this case, such others will include me. As such, and in line with the principles of the ESE, I want to propose some terms of engagement between us.

Firstly, it is possible to forgo this invitation to become a wayfarer. As you will enter and make your way across this knowledge-land-scape, you will have the possibility to keep following this “cut”, and read “about” my process of wayfaring the BearWatch project. Should you choose to accept (some of) my invitations (along the way), however, this should come with the understanding that such a decision entails your willingness to become an active and immersed agent in the ensuing material opening and closing opportunities for shared meaning-making within my research.

Secondly, the knowledge-land-scape, that you are about to enter is comprised of (digitized) materials. They are ethnographic traces like voice notes, photos, drawings, edited videos, written notes, posters and presentations, as well as academic texts and workshops, resulting from the more-than-human aesthetic encounters that were part of my fieldwork. My knowledge-land-scape is explicitly not about providing “direct” access to the land or Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (nor is such a thing possible, or desirable). It adheres to Inuit-driven EEE protocol 3 , in that it respects cultural “differences”. My work does not somehow make otherwise “remote” regions legible, accessible or available for consumption. Nor does it take the liberty to “represent” IQ, or “map out” Inuit Nunangat as if it were a blank slate, or “empty” space available for inscription or re-interpretation by non-Inuit researchers like me. As such this work doesn’t work towards descriptive representations of Inuit land or Knowledge. It acts instead as an emergent topology that consists of the insights that emerged as part of my research encounters, and materializes in-between subject-object, reader-author, and land-scape.

As such not everything is possible within this knowledge-land-scape. The land-scape as it emerges within this web-based platform is not meant to sketch a comprehensive and complete overview of the institutional or socio-political apparatus of community-based polar bear management. It is rather bounded by the particular more-than-human encounters of my fieldwork, the apparatus of western science and polar bear co-management, available resources and the technical affordances of the software with which it was built- as well as the intra-dynamics of all these matters and my decisive cuts as a researcher.

As you try to figure out what this concretely means, you sport a formation of rocks. You could take a moment to orient and prepare for your upcoming journey. If you step onto this rock right next to you, you will get a better view of your surroundings. It perhaps provides possibilities to gain some deeper understanding of what such shared-meaning making and its boundaries have to do with knowledge conciliation and the ESE. Otherwise, you could just get going and learn more about how I positioned myself within the BearWatch project.

Wayfaring as a Sensitizing Method

Use text from 1.2 word doc here

The BearWatch Project

The track you are currently following will cut along the unfolding developments of the Genome Canada funded research project called ‘Bearwatch: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge’ – hereafter referred to as ‘Bearwatch’. Bearwatch ran between 2015 and 2023, during which it sought to meaningfully engage IQ in its development of a new non-invasive genomic polar bear monitoring toolkit. The project was a collaboration between northern communities in the Nunavut Settlement Region and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, HTAs in Gjoa Haven and Coral Harbor, the Inuvialuit Game Council, the governments of Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon, the Canadian Rangers, and researchers and students from multiple universities across Canada and beyond.

Most researchers and policymakers in the field of polar bear science more generally – and on the BearWatch project particularly – are trained in a variety of natural science disciplines of the western academic institute, or they are Inuit knowledge and rights holders. I, myself, am a white, queer, settler-guest researcher from the Netherlands with a background in the applied arts and social sciences. Approaching this research context as a non-Inuit researcher from such a different cultural and disciplinary place of beginning than most other Bearwatch team members and polar bear monitoring practitioners, has required me to negotiate and navigate my own way alongside many of the project’s activities.

This particular cut allows you trace the unfolding of the BearWatch project along multiple (sometimes parallel) tracks in a manner that also allows for you to thread your own way through this knowledge-land-scape. As such, this cut is not so much about deriving at conclusive take-aways about ethical knowledge conciliation within BearWatch, as much as it about extending material opportunities for you, the reader, to become knowledgeable alongside my creative practice (auto-)ethnography with the research project.

Point of Decision-making

Before you head further down this cut, you have a choice to make. Will you trace the most straightforward path across the BearWatch project, engaging just with the descriptive elements of my research? Or will you thread your own way alongside me, becoming an intra-dependent maker of meaning? The former choice will be a more disconnected, conventional experience, whereas the latter will be more of an immersed narration, that places you “within” my knowledge-land-scape.

In this line of thought you realize it might be helpful to look up the meaning of “intra” dependency, as opposed to “interdependency”. Then you realize this entails taking off your mitts and taking your phone out of your pocket. It’s freezing, and your phone might not last long in these temperatures. If you choose to keep going instead, you will move straight to reading about the TEK workshops that were held in the community of Gjoa Haven in 2019, as to inform a feasibility study on future community-driven polar bear fecal sample collection.

Detour: look up the meaning of "intra-dependency"

TEK Workshops

Polar bear populations- and thus Indigenous harvesting- are, under the international agreement on the conservation of polar bears, to be managed ‘in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best available scientific data available’ (Lentfer, 1974). The NLCA states furthermore that ‘Inuit must always take part in decisions on wildlife’ (NTI 2004), while part 1 of its wildlife act, states that ‘the guiding principles and concepts of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) are to be described and made an integral part of the management of wildlife and habitat’ (Wildlife Act 2003).

In response to the ‘legal authority of land claim agreements, asking that IQ/TEK be used to make management decisions’, and ‘to increase community ownership of polar bear monitoring through community-based collection and knowledge sharing’ the BearWatch project was designed to include a “Genomics and its Environmental, Economic, Ethical, Legal and Social aspects (GE3LS)” component (BearWatch research proposal, 2016 p.30-31).

As part of this GE3Ls activity three TEK mapping workshops were co-designed with the HTA of Gjoa Haven to ‘identify TEK gaps’ and ‘fill them’. The temporal and spatial polar bear TEK that was collected, was processed and published in the MES thesis of Scott Arlidge, another student that participated in the project. It ‘provides a georeferenced knowledge base that displays information on polar bears including harvest sites, bear movement, denning sites, and hunter knowledge areas’ (Arlidge, 2022 p.13). The data as shared in this publication is presented in his thesis as i) ‘a historical record of polar bear knowledge for the community of Gjoa Haven’; and ii) ‘as a guide to areas of high polar bear activity for future targeted polar bear monitoring effort’s’ (Arlidge, 2022 p.ii).

You have taken a moment to sit down and read Arlidge's thesis. As you are about to check out what Genome Canada has written on their website about GE3LS, someone brings up the existence of a nearby shipwreck: Knowledge “integration”. They suggest you go check it out to get another perspective on bringing IQ together with western sciences.

You weigh your options, as there is also another workshop lined up for tomorrow. The Gjoa Haven HTA has urgently been trying to get the BearWatch researchers to turn their focus towards the available polar bear harvest quota. 20 people will come to talk about how a harvesting moratorium from 2001 has had reverberating impacts on them up until today.

Wrecksite: Knowledge "inclusion"

Workshops Summer 2019

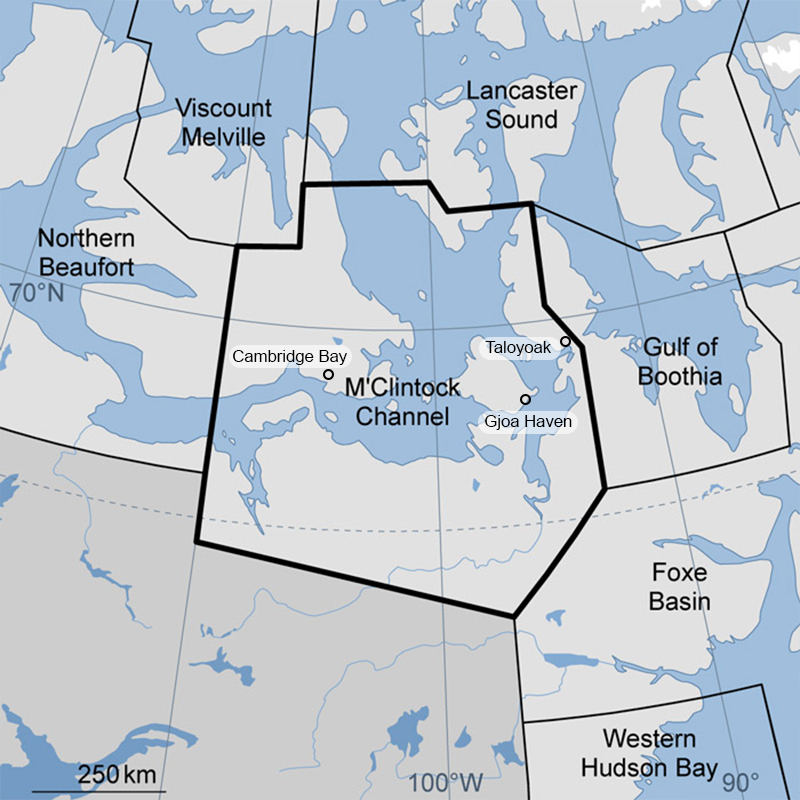

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Based on a desire for recognition and acknowledgement of the impact of these polar bear quota regulations, two workshops were co-organized in addition to the original TEK workshops that were planned to take place over the summer of 2019, to discuss and document the testimonies of Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members

The workshops were advertised over the radio in both English and Inuktitut (Inuit language), and interested individuals signed up through the HTA. One workshop was held May 15, 2019 in the evening with 10 participants and one on May 16 in the morning with 11 participants. These participants comprised mainly older male community members, many of whom had hunted, or still hunt polar bears. There were two female participants in each workshop. Three of the participants were between the ages of 20 and 40, with the remainder older. These two workshops focused specifically on the impacts of polar bear hunting quota reductions on the community. The workshop questions were co-designed by the BW academic researchers and HTA representatives and were asked in both English and Inuktitut to prompt discussion. The format however remained open-ended, meaning that "off-script" discussions were encouraged during the workshop, and occasionally specific members were asked to participate in answering particular questions because of their connection to the issue, as identified in previous interviews or by other community members. Two BW researchers and an interpreter would ask the pre-designed questions and prompt discussion, while a third BW researcher made notes. Both workshops were audio-recorded.

The BearWatch PI's and Gjoa Haven HTA-board want to use the recordings of these impacts workshop as primary materials for an academic paper. They ask you to write it, even though you have just joined the project and have not yet set foot into the community.

What to do?

Although you understand that writing “about” other people’s experiences doesn’t exactly sound ethical, you have little time and need to keep going. Your first fieldwork trip to Coral Harbour is upcoming, and you need to prepare for that. Besides, the Gjoa Haven HTA wants a publication, no need to complicate things further. Alternatively you can stay with the trouble and explore in what ways the “Politics of recognition” complicates such writing practices. Maybe you have already leaned into such tensions, and all that is left now, is to organize a conference call and have a conversation with the Gjoa Haven HTA about these complexities- which will redirect you (back) to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder.

Stay with the trouble: The politics of recognition

Detour to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder Testimonies

(Re)turn to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder Conversations

Coral Harbour First Trip 2020

Alongside funding from Genome Canada, the project PI’s also successfully applied to the Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada/ World Wildlife Fund to fund ‘traditional knowledge research and a denning survey in Coral Harbour, Nunavut’ (Schedule H, 2020, March 31. This intended study included documenting polar bear TEK in Coral Harbour, surveys of vacated dens by locals to collect a variety of samples and data, and the initiation of a collaborative effort with the high school to train students in land-based surveys.

Covid-19

The den survey and TEK collection activities in Coral Harbour were planned for March and April, but were postponed due to COVID-19. The Hamlet of Coral Harbour requested outside visitors stay away the day before most of the BearWatch team was set to arrive in the Hamlet, and the BearWatch PI’s respected their wishes. I had, however, travelled North a day early, and arrived in the community on exactly the day that the Covid-19 epidemic was declared pandemic. Non-resident travel bans came into effect in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories immediately, as well as physical distancing requirements within communities.