Aesthetic Action: Difference between revisions

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Knowledge as fluid and -ever becoming: Knowledge itself, like culture, is not static, and actively regenerated across time and space. Knowledge as something more practical/tacit that flows in-between, among, and around different performative bodies is often not acknowledged in more positivist traditions of science that seek static, objective and representative measurability. It however aligns well with Indigenous theories of knowledge that view ways of being and knowing as existing and manifesting through a web of more-than-human relationships. Many Indigenous people share an understanding of knowledge not as simply understanding relationships within Creation, but rather as Creation itself (McGregor 2004a). Knowledge is something one does. To ensure its ongoing existence, knowledge, like land, is something that needs to be practised, not harnessed, captured, incorporated or integrated. Knowledge as creation is constantly in motion. This convergent process itself reinforces the idea of knowledge in terms of ongoing practice, rather than historically static ‘tradition’ (Ingold, 2010). The middle circle of the ESE where different knowledge systems may ‘encounter’ is no different, rather than a static blending of data, it represents an ongoing process and practice of being with. This focus on process and practice of the ESE affirms Indigenous conceptualisations of knowledge as not being something to be accumulated or measured as neatly codifiable data, but rather something that proceeds along ways of life, and is then shared via narrative forms. | Knowledge as fluid and -ever becoming: Knowledge itself, like culture, is not static, and actively regenerated across time and space. Knowledge as something more practical/tacit that flows in-between, among, and around different performative bodies is often not acknowledged in more positivist traditions of science that seek static, objective and representative measurability. It however aligns well with Indigenous theories of knowledge that view ways of being and knowing as existing and manifesting through a web of more-than-human relationships. Many Indigenous people share an understanding of knowledge not as simply understanding relationships within Creation, but rather as Creation itself (McGregor 2004a). Knowledge is something one does. To ensure its ongoing existence, knowledge, like land, is something that needs to be practised, not harnessed, captured, incorporated or integrated. Knowledge as creation is constantly in motion. This convergent process itself reinforces the idea of knowledge in terms of ongoing practice, rather than historically static ‘tradition’ (Ingold, 2010). The middle circle of the ESE where different knowledge systems may ‘encounter’ is no different, rather than a static blending of data, it represents an ongoing process and practice of being with. This focus on process and practice of the ESE affirms Indigenous conceptualisations of knowledge as not being something to be accumulated or measured as neatly codifiable data, but rather something that proceeds along ways of life, and is then shared via narrative forms. | ||

<span class=" | <span class="pop-up vista link" data-page-title="The ESE (Space)" data-section-id="0" data-encounter-type="Vista">[[The ESE (Space)|Vista: The ESE (Space)]]</span> | ||

=Aesthetic Action and the ESE= | =Aesthetic Action and the ESE= | ||

Revision as of 22:25, 8 December 2024

abstract and acknowledgements

Introduction

Ever since the 1990’s there has been an ongoing and widespread interest among community-based environmental conservation researchers to engage with Indigenous Knowledge (IK). Such interest was initially mostly geared towards broadening and improving scientific knowledge and management in conservation research (see e.g., Freeman, 1992; Mailhot 1993; Berkes, 1994; Brooke, 1993; Inglis, 1993; Huntington, 2000). Over the last thirty years however, this question of how and whether it is even possible to relate knowledge systems rooted in two different ways of being and knowing the world - respectively western-based science and those knowledge systems specifically attributed to Indigenous peoples - has undergone major changes. Self-determination efforts, increased awareness around the need for western-based science to decolonize and become more inclusive, as well as a shifting paradigm regarding the relationship between the natural environment and Indigenous people, have all led for the efforts of knowledge relating in conservation research and management to become more equitable and inclusive. At least in theory. It has also been revealed to be a ‘site of significant struggle’ (Tuhiwai-Smith, 1999). Linda Tuhiwai-Smith identifies such struggle in research as taking place between ‘the interests and ways of knowing of the West and the interests and ways of resisting of the Other’ (ibid, p.2, capitalization in original). It brings to the fore questions of whose knowledge is deemed valid - according to whose qualifiers? And which research questions get asked in the first place. Whose interests are served with research? And who owns the research? Rather than a technical challenge of filling gaps in scientific knowledge, knowledge relating within environmental research and management has become more explicitly a question of relational encounter, and on whose terms such encounter takes place. The question of how to ethically relate Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledges has increasingly been recognized to be just as much about Indigenous and settler(-state) reconciliation as it is about various forms of knowledge co-production and ethical engagement within research.

Terms of Engagement

Knowledge Conciliation as Ethical Engagement, Practice, and Processes

ITK reported in 2018 in their Inuit National Strategy on Research that, despite prevalent claims of knowledge co-creation or -integration in wildlife research reporting from the Canadian Arctic, Inuit are rarely involved with setting the research agenda, monitoring compliance with guidelines for ethical research, and determining how data and information about people, wildlife, and environment is collected, stored, used, and shared (ITK, 2018). This indicates that legislative agreements like the NLCA, on its own, are not enough to secure meaningful engagement between western-based science and IQ. Power dynamics around knowledge relating takes place ‘in-between, beyond and underneath formal structures’ (Lindroth et al., p.8, 2022). Such is reiterated by the Indigenous Circle of Experts who state that relationships need to be negotiated at all levels, and on an ongoing basis (ICE, 2018). Establishing ethical relationships is a regenerative, situated process, and needs to be renegotiated in every context, at all scales. Reform at the institutional level to support- and resource Inuit-led research is just as important as negotiating terms of engagement and developing ethical research practices at the situated research project level. Relating different knowledge systems in its most radical form, if at all, should therefore not only be employed as a praxis of inclusive research, but it should also be its precursor; establishing terms of engagement, defining what inclusivity means - and whether that should be the goal in the first place. The Ethical Space of Engagement (ESE), as a guiding framework has potential to reframe the challenge of knowledge relating away from one that is data-driven, towards one of process and practice, and to include such negotiation of terms of engagement.

The ESE, as formalized by Ermine in 2007, derives from Indigenous traditions of nation-to-nation conciliation, and can be applied to create a space or physical site that functions as an in-between; a meeting space that can facilitate trans-cultural dialogue and cross-validation between different communities, nations, or knowledge systems. By providing an in-between, or a ‘third space’ (see for another example of third space Turnbull, 1997), the model re-imagines opportunity for encounter and opens space to explore and practice the principles of respect and reciprocity underlying such encounter (Ermine, 2015; Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018).

By engaging this framework to think of ethical space not as an absolute state or existing physical site, but rather in terms of how the ethical space can facilitate encounter(s) through an ongoing state of negotiation and becoming, as a field of tension and a coming together in difference, it parts from past science-based practices and may resist the western-based academic research establishment along the following lines;

Understanding knowledge relating as a set of practices and values: The western-based scientific tendency to compartmentalize knowledge(s) into narrow codifiable packages of data, conceptualizes the practice of knowledge relating as a static binary of siloed knowledge systems and a data gap to be navigated through approaches like ‘bridging- ‘, ‘integrating-’, ‘linking- ‘or ‘blending’ knowledges. As the ‘perceived degree of separation’ between different knowledges ‘narrow’ (Evering, 2012), intersecting spaces, interfaces or similarities among IK and western science are sought out, as to then create opportunities for collaboration, co-creation and co-learning on the premise of this ‘common ground’ (e.g., Foale, 2006; Berkes et al. 2006; Aikenhead and Michell, 2011). The theoretical ideal of such a common ground approach (see middle diagram in figure 1) focussed on similarity, and in practice often results in an integrative scientization of Indigenous Knowledges (see left diagram in figure 1). Scientization of indigenous knowledge happens when scientists only engage with those elements of IK, for example narrowly defined Traditional Ecological Knowledge, that allow for western-based categorisation (Agrawal, 2002), translation (Smylie, 2014) and validation (see Brook, 2005, in response to Gilchrist et al. 2005) – or where IK is ‘distilled’ and translated until nothing more is left than numbers and polygons prepared for easy incorporation into western-based research and management (Nadasdy, 1999; Agrawal, 2002). The consequences of such scientization are non-trivial. It does not only ‘displace the very thing it is meant to represent—the lived experience’ (Miller & Glassner 2004), it also renders knowledge integration ‘a neutral, technical exercise (…) towards which nobody can politically object’ (Nadasdy, 2005). The integration of TEK in western research and management framework becomes a technical problem to be solved (e.g., Huntington, 2005; Wenzel, 1999 ; Natcher and Davis, 2005; Clark et al. 2008). As such, knowledge integration can potentially assimilate Indigenous knowledge and people into Euro-Canadian governance systems, de-politicizing the system of co-management itself, and forming a barrier to self-determination (Nadasdy, 2003; Agrawal, 2002; Simpson, 2001; Stevenson, 2004; White, 2006; Ellis, 2005). Applying the ESE as a guiding frame, shifts thinking about knowledge relating from a static end-goal, towards a dynamic and ongoing state of becoming in a third space. This space, conceptually outside of each knowledge system, allows for the mediation of terms by which different are related. While cultural difference, diverse positionalities and institutional mediation between Indigenous peoples and western societies can all be acknowledged, it is the practice of negotiating encounter that is central to this framework. ‘The space offers a venue to step out of our allegiances, to detach from the cages of our mental worlds and assume a position where human-to-human dialogue can occur.’ (Ermine, 2007). The ESE takes into account relations, values, and knowledge and aims to build new agreement beyond those of already existing treaties or mandates. By focussing on such processes, it allows for knowledge relating to be approached as a political issue, rather than a technical project (e.g., Laurila, 2019).

Respecting incommensurability: The ethical space of engagement as a political frame also leaves room for irreconcilability; for elements of each knowledge system not to be engaged with (Simpson, 2001; Tuck and Yang, 2014) or to be considered sacred (Archibald, 2008). Knowledge relating that takes incommensurability into account, does not dismiss the project of encounter, but it embraces difference (Jones and Jenkins, 2008) and acknowledges the fact that processes needed for ethical engagement can claim space outside of western institutes (Robinson and Martin, 2016). It involves the resurgence of Indigenous knowledges, laws, languages, and practices as integral elements of Indigenous self-determination, rather than its incorporation into dominant way of knowing and being in the world (Corntassel 2012 ; Simpson, 2004; 2011, p 17). What is required from settler(-immigrant) researchers wanting to ethically and equitably engage with Indigenous knowledges and peoples, is solidarity rooted in the acceptance of difference rather than common ground, solidarity that endures in a state of unsettlement, and solidarity that accepts the existence of demarcated spaces, stories and culturally protected knowledge which remain sacred, and are to be kept within the community (Tuck, 2009; Tuck & Yang, 2014; Archibald, 2008). Such commitments need to move beyond theory, or metaphorical applications that allow for settler ‘moves towards innocence’ (Tuck and Yang, 2018). In accordance with the work of foundational Indigenous thinkers like Smith (1999), Wilson (2008) and Kovach (2010) it’s not so much about what you say you will do as a researcher, it’s about the practices that accompany those words and the consequences of such actions.

Knowledge as fluid and -ever becoming: Knowledge itself, like culture, is not static, and actively regenerated across time and space. Knowledge as something more practical/tacit that flows in-between, among, and around different performative bodies is often not acknowledged in more positivist traditions of science that seek static, objective and representative measurability. It however aligns well with Indigenous theories of knowledge that view ways of being and knowing as existing and manifesting through a web of more-than-human relationships. Many Indigenous people share an understanding of knowledge not as simply understanding relationships within Creation, but rather as Creation itself (McGregor 2004a). Knowledge is something one does. To ensure its ongoing existence, knowledge, like land, is something that needs to be practised, not harnessed, captured, incorporated or integrated. Knowledge as creation is constantly in motion. This convergent process itself reinforces the idea of knowledge in terms of ongoing practice, rather than historically static ‘tradition’ (Ingold, 2010). The middle circle of the ESE where different knowledge systems may ‘encounter’ is no different, rather than a static blending of data, it represents an ongoing process and practice of being with. This focus on process and practice of the ESE affirms Indigenous conceptualisations of knowledge as not being something to be accumulated or measured as neatly codifiable data, but rather something that proceeds along ways of life, and is then shared via narrative forms.

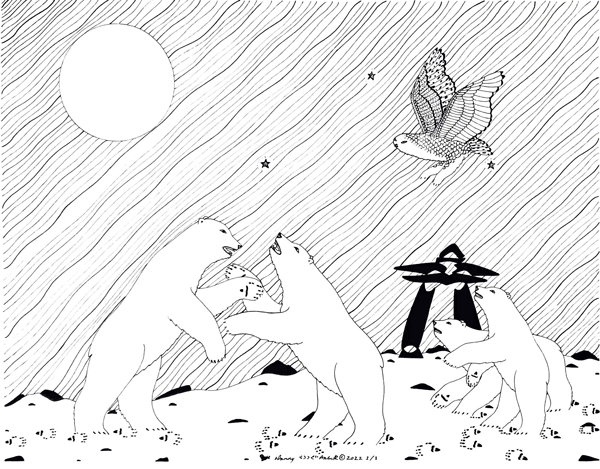

Aesthetic Action and the ESE

How we understand aesthetic action within a framework of the ethical space of engagement requires tackling the issue of ethics in a transcultural context. Contemporary western aesthetics combine ethics and aesthetics under value theory. The Aristotelean understanding of value theory would see us make moral choice based on our values to optimize ourselves as a virtuous person. But within this virtue theory, how we know something is moral depends on the values we hold – and those values are culturally loaded. As mentioned above, I aim to stay away from such moral understanding of aesthetics, due to their strong affiliations with western paradigms which I try to decentre.

Aesthetic (in)action in BearWatch

You find yourself at a crossroad. Each of the paths forwards will guide you across a case-study. These case study perform events within the BearWatch project that could possibly be marked as Ethical Spaces of Engagement.