Voices of Thunder: Difference between revisions

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

<span class="detour link" data-page-title="Aesthetic_Action" data-section-id="9" data-encounter-type="detour">[[Point of Beginning Animated Graphic Documentary|Detour to Cut 2: Aesthetic Action]]</span> | <span class="detour link" data-page-title="Aesthetic_Action" data-section-id="9" data-encounter-type="detour">[[Point of Beginning Animated Graphic Documentary|Detour to Cut 2: Aesthetic Action]]</span> | ||

<span class="detour link" data-page-title="Voices_of_thunder" data-section-id="0" data-encounter-type="detour">[[ | <span class="detour link" data-page-title="Voices_of_thunder" data-section-id="0" data-encounter-type="detour">[[#Places of Beginning|Detour to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder “Places of Beginning”]]</span> | ||

<span class="return link" data-page-title="Wayfaring_the_BW_project_Point_of_Beginning" data-section-id="5" data-encounter-type="return">[[Wayfaring the BW project Point of Beginning#2. Workshops Summer 2019|Return to Cut 3 Wayfaring the BW project: "Workshops 2019"]]</span> | <span class="return link" data-page-title="Wayfaring_the_BW_project_Point_of_Beginning" data-section-id="5" data-encounter-type="return">[[Wayfaring the BW project Point of Beginning#2. Workshops Summer 2019|Return to Cut 3 Wayfaring the BW project: "Workshops 2019"]]</span> | ||

Revision as of 20:40, 18 November 2024

Abstract

International polar conservation is often presented as a success-story. Population numbers are considered to have recovered from their historical low in the 1960s, and the international cooperation around the species is considered evidence of successful ‘science diplomacy’. What is often left unconsidered in these celebrations are the uneasy tensions that sometimes exist between international agreements on the conservation of polar bears and territorial co-management regimes that have emerged from Indigenous Land Claims Agreements. Although mandated to incorporate Inuit rights, -values, -culture and -knowledge in polar bear decision-making, such territorial co-management regimes are also embedded within international agreements that exert pressures for data-driven management which has traditionally focussed narrowly on population recovery. The conciliation of different, and sometimes competing interests, remains an ongoing challenge for polar bear co-management in Inuit Nunangat, and has in the past led to controversial decision-making. For example the implementation of a polar bear hunting moratorium in the M’Clintock Channel Polar Bear Management Unit in Nunavut, Canada. Although implemented in 2001, and revoked in 2004, this moratorium has ongoing impacts for many community members of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, today, in terms of lost income, -culture, and -inter-generational knowledge transfers. In a collaborative effort we; Gjoa Haven’s HTA and researchers of the BW project, appeal together for wider recognition of these ongoing impacts and an ethos of accountability through different avenues; i) A 20 minute co-created motion graphic documentary, ii) An academic publication, and iii) A webpage.This manuscript/cut draws attention to the collaborative decision-making along the way, and how our different co-creative practices have allowed for different “ethical” ways of engaging with Gjoa Haven’s testimonies across research partners.

1. Introduction

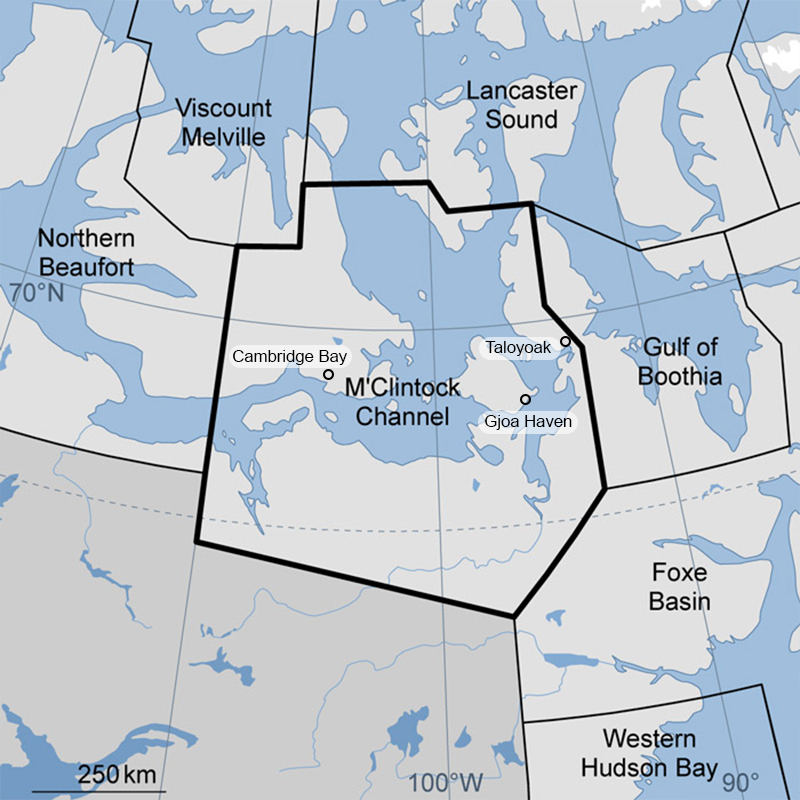

This manuscript/cut and its related work emerges from five years of ongoing conversations between representatives of the Gjoa Haven’s Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut (figure 1) and Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario researchers. It is based on a series of community-based workshops conducted in the summer of 2019 for a ‘Genome Canada’ sponsored large-scale polar bear monitoring project entitled “BEARWATCH: Monitoring Impacts of Arctic Climate Change using Polar Bears, Genomics and Traditional Ecological Knowledge” – hereafter, simply, BW.

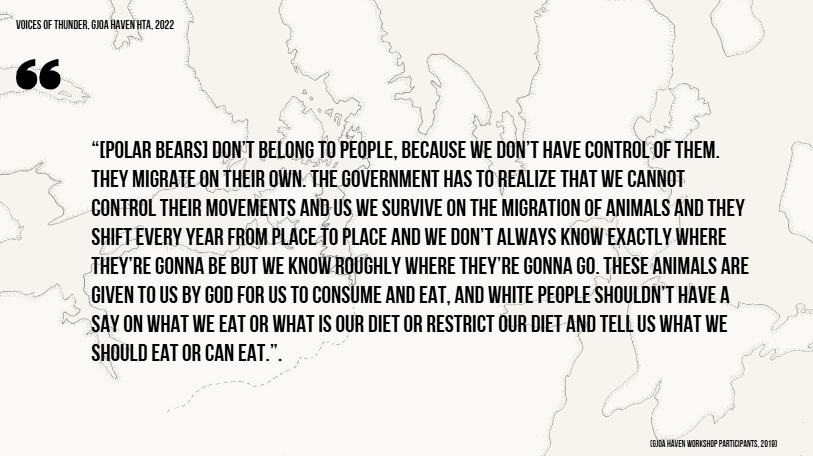

Several Inuit communities across Inuit Nunangat (homeland of Inuit of Canada’, ITK, 2018) have collaborated with the BW project to combine Inuit Knowledge with western science in developing a community-based, non-invasive, genomics-based toolkit for the monitoring and management of polar bears. One of these collaborating communities is Gjoa Haven, whose Hunters and Trappers Association (HTA) representatives have a research relationship with BW co-PI Peter Van Coeverden De Groot that has stretched across more than 20 years. Over the years, one issue that was brought up repeatedly by Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and other community members, concerned the effects of severe polar bear hunting quota reductions introduced to the community in 2001.

The M’Clintock Channel (MC) Polar Bear Management Unit (PBMU) used by hunters from Gjoa Haven, Cambridge Bay and Taloyoak (see figure 1), was in 2001 subjected to a three-year polar bear moratorium (a full suspension of hunting). In 2005, the moratorium was lifted and Gjoa Haven and Cambridge Bay signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB) for alternating quotas of one and two tags per year, while Taloyoak did not sign the MOU at all, and therefore did not receive any tags from the MC management unit between 2001 and 2015. Both Taloyoak and Cambridge Bay- unlike the residents of Gjoa Haven- however, also have traditional hunting grounds outside of the MC PBMU. So, when the quota in MC PBMU was significantly reduced from an average of 33 bears annually before 2000 (US FWS, 2001), to only 3 bears annually (NWMB, 2005), the community of Gjoa Haven was disproportionately impacted. No other community in Nunavut or the Northwest Territories has experienced such a (near) moratorium over such an extended period of time. Despite a more recent rise in tags in 2022, these impacts continue to be felt today. Hunting polar bears is an important part of Inuit culture. It facilitates inter-generational knowledge transmission of on-the-land skills, and provides a significant source of income within Inuit mixed-economies (Dowsley, 2008; Wenzel, 2011). After two generations of hardly being able to hunt polar bears, Gjoa Haven hunters still seek recognition for the impacts such quota-decisions have had in terms of lost income, loss of culture, and loss of intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Such accepting testimony, however, isn’t limited to a ‘passive reading’ of the quota impacts on the community. You are hereby instead invited to become a “wayfarer”.

2. Terms of Engagement

Becoming a wayfarer entails a willingness on your part to become an active and immersed agent in the ongoing material opening and closing of opportunities for meaning-making within my research. As such a role requires response-ability, from your part it is thus also important to formulate the boundaries and benchmarks particular to such a social contract, before you continue. Terms of engagement if you will.

Per definition, this knowledge-land-scape is not the land, nor the ice, or the rocks, seasons and animals with which Inuit and other knowledge holders become knowledgeable and move through the world. The (digitized) materials that de/markate this knowledge-land-scape are rather ethnographic traces like voicenotes, photos, drawings, edited videos, notes, and posters and presentations, as well as academic texts and workshops, that emerged from my fieldwork.

This knowledge-land-scape is explicitly not about providing access. It adheres to Inuit-driven EEE protocol 3 (ICC, 2020), in that it respects cultural “differences”. My work does not somehow make otherwise “remote” regions legible, accessible or available for consumption. Nor does it take the liberty to “represent” the experiences of Gjoa Haven’s community-members, or their knowledge. My knowledge-land-scape is not meant to be taken as a descriptive representation, but instead more of an emergent event. An emergent topology that materializes responsively in-between subject-object, reader-author and land-scape.

Not everything is furthermore possible within this knowledge-land-scape. The platform as a whole is not meant to sketch a comprehensive and complete oversight of the institutional or socio-political land-scape of community-based polar bear management. It rather prioritizes the particular, intra-dependent, and partial perspectives over a ‘god trick’, in which one claims to see, but remains oneself unseen (Haraway, 1988 p.581). If a reader would want to explore the whole knowledge-land-scape, for example, they would likely have to re-visit it multiple times. Such partiality also, explicitly, refers to the platform itself. The boundaries and possibilities of the platform are de/markated by how my own aesthetic actions in the field have diffracted with other agents, including the research apparatus of western science, at play in the field of polar bear monitoring research. Although the knowledge-land-scape thus indeed materializes for the reader based on their own choices, the possibilities and conditions for these choices are nevertheless still bounded by my decisive cuts as a researcher.

Where to next?

While you might have been wondering what this all means, you have stumbled upon a Vista. This Vista is a viewpoint, it will help you orient. You can take a moment to take the view in- this Vista is called "The Ethical Space of Engagement". Perhaps it will help you direct your course along the way. Alternatively, you can keep on going. You have heard that researchers of the BearWatch project have already organized some workshops last year, and they might have made some recordings.

Vista: The Ethical Space of Engagement

3. From purveying voices towards accepting testimony.

Indeed, in the summer of 2019, two workshops were co-organized to discuss and document testimonies on the multiple impacts of the polar bear quota reductions on Gjoa Haven hunters and other community members. The recordings of these workshops and its accompanying notes became the primary materials which were transferred to me in 2020, after I had just started as a new PhD student on the BW project. I was requested to process the recordings and describe Gjoa Haven’s experiences in an academic publication for a larger academic audience. As a researcher who had not yet set foot in the community of Gjoa Haven, such an "assignment" made me feel uneasy; Who was I to write an academic paper that conveyed the lived experiences of people who I had never even met?

What to do?

The most straightforward solution to these questions seems to organize a call with the Gjoa Haven HTA. The Principle Investigators of the project are supportive, and organize a meeting to discuss a way forward. It however also seems necessary to “stay with the trouble”, considering that the BearWatch project and its non-Inuit researchers seem to be entangled with the larger apparatus of science-based polar bear management that have contributed to the impacts as shared in the workshop. Do you first gather more information on the workshops that were conducted in 2019, or do you keep going and take the call? Or do you do neither and stay with the trouble?

Stay with the trouble: The politics of recognition

Detour to Cut 3 "Workshops Summer 2019"

3.1 Ongoing conversations.

The choice to continue having conversations with the Gjoa Haven HTA board and other community representatives about what they were seeking to achieve by sharing their testimonies with us, was crucial to negotiating a more responsive space for collaboration. Not only did it provide for opportunities to collectively discuss how to process, interpret and present the workshop recordings, but it also helped in gaining a shared understanding of the purpose to which the Gjoa Haven HTA had requested such workshops in the first place.

We arranged a total of five separate meetings between the Gjoa Haven HTA, myself, and three BearWatch PI’s- each lasting about three hours. Due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic the first three of these meetings- and thus also my introduction to the HTA-board- took place by remote conference phonecalls in the fall of 2020.

During these meetings we navigated together how to proceed with the experiences that were shared during the impact workshops. These calls were not pre-structured or accompanied by an agenda, but we did turn to a series of critical questions suggested by Linda Tuhawali Smith (1999) to guide us in our conversations; “What research do we want to do? Who is it for? What difference will it make? Who will carry it out? How do we want the research done? How will we know it is worthwhile? Who will own the research? Who will benefit?” Among multiple other insights, this led to a clear articulation of the main objective of Gjoa Haven HTA representatives for publishing the experiences shared in the workshops- which we collectively formulated as follows;

‘We want our “voices of thunder” to echo everywhere. We want everyone to know what happened to us. We seek acknowledgment and apologies for suffering the consequences of the quota regulations; a loss of culture and knowledge, as well as increased danger due to the rising number of polar bears around our communities. Inuit knowledge in terms of accuracy and inherent value needs to be recognized and better acknowledged. We want better integration of Inuit knowledge in survey research, like for example accounting for seasonal changes. Scientific monitoring surveys have limitations, we ask that researchers will recognize and take Inuit observations more seriously’.

The Gjoa Haven HTA seeks recognition. The kind of recognition that they seek is however multifaceted. Beyond acknowledgement and apologies for the quota reduction impacts, the Gjoa Haven HTA also seeks validation, and better “integration ” of their knowledge in research and management. The Gjoa Haven board also speak of wanting to have their voices of thunder “echo everywhere” - a vision of broad dissemination that extends beyond the scientific community, towards other Nunavut communities and wider Canadian society. Aside from the politics of recognition that are connected to academic publishing, by itself, it would likely not achieve the reach of audience that the HTA was seeking. To more completely pursue such desired forms of wide recognition, we realized that additional avenues of knowledge creation were needed in parallel to academic publishing.

Keep on going to learn more about these different avenues for knowledge creation. Or take a minute to dwell on the material circumstances under which those first calls were made.

Invitation: Thinking from the road during covid-19

3.2 Multiple voices

Based on our conference calls, and also meetings in Gjoa Haven itself over the Summer of 2021, we were able to set a course. In addition to academic scholarship, we decided to co-create multiple audio/visual outputs, and one-pager communications,. Output like video and websites are better formatted for broad dissemination through publicly accessible venues like social media, and the internet. One-page communications are on the other hand more suitable for political advocacy. Across the summer of 2021, and spring 2022, we arranged for an eight-week period of in-person co-creation and conversations in Gjoa Haven on how to proceed in sharing Gjoa Haven’s “Voices of Thunder”. During these periods, we discussed potential knowledge outputs and forms of writing- or otherwise- presenting the experiences shared in the workshops. We constructed narrative sequences and in 2021 we also started to co-produce one of our three main knowledge outputs; the motion graphic documentary In 2022, we reviewed versions of our academic paper, reconfirmed the meaning of several of the statements that were quoted in the workshop recordings through additional conversation, and we screened edited versions of several videos we had co-produced prior. Part of these processes was also to navigate the subject-position of the academic scientists in ‘telling’ these stories of quota reduction impacts for the community, in an ongoing manner. Our conversations included discussions on the challenge of presenting Gjoa Haven’s voices and objectives, without the academic partners speaking for them. Instead of reproducing yet another damage-centered study that portrays an Indigenous community primarily as ‘broken, emptied, or flattened’ (Tuck, 2009), or the social scientists as an invisible and elevated ‘purveyor of voices’ for those that are suggested to be “voiceless” (Spivak, 1988 ; Simpson, 2007; Tuck and Yang, 2014 p.226)- we explored how exactly each of our voices could be appropriately leveraged within different knowledge products, including as part of writing an academic paper. For example, in the motion graphic documentary, the experiences shared by the workshop participants speak through the voices of Gjoa Haven community members themselves. In the academic paper, on the other hand, the voices of the BW scientists are more prominently present. Not through the employment of theoretical frameworks and methodological analysis to translate, validate or otherwise explain the experiences shared by Gjoa Haven’s HTA representatives, hunters and community members, but rather by conducting a direct, ‘unromantic’ (Jones and Jenkins, 2008), “testimonial reading” (Boler, 1997).

You pass a landmark. Maybe you have seen it when you stopped earlier to check out the Vista: The ethical Space of Engagement. Now, however, you are looking at it from a particular angle, and it gives you an insight about “multiple sites of enunciation”. Do you want to take a closer look at the landmark, and see how the different voices at play have positioned themselves in each form of output? Or do you keep going and learn more about “testimonial reading”?

Landmark: Multiple sites of enunciation

3.3 Testimonial reading

To conduct a ‘testimonial reading’ of the experiences of Gjoa Haven’s community members, is to move beyond passive empathy, and towards an acceptance of testimon y that requires bearing responsibility. It asks the recipient of such testimony to commit - to rethink their assumptions, to challenge the comfortable concept of being a ‘distant’ other, and to recognize the power-relationships between the “reader” and the testimonial “text” (Boler, 1997). By conducting such a testimonial reading of the experiences shared by Gjoa Haven community members, we can both engage with the experiences shared in the workshop, ànd with the appeal of the Gjoa Haven HTA for wider recognition.

Terms like ‘testimony’ or ‘witnessing’ are ideologically and politically loaded. They furthermore may mean different things within different contexts. To ‘witness’, when considered in the context of this cross-cultural research collaboration, doesn’t take up the western legal definition of being an (eye)witness as it would in the context of a legal court. It rather takes up meaning that aligns more with the ways in which it was applied in the public fora of Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Committee hearings. Witnessing, as defined in schedule N and later on the TRC website (TRC.ca), is to take responsibility for ‘accepting testimony’ on historical events, even if one hasn’t directly experienced these events themselves. This form of witnessing is active. It is not merely listening. To witness, is to enter into a very specific and powerful relationship between witness and storyteller (see Nock, in Gaertner, 2016 p.138). This form of witnessing is particularly important to Indigenous cultures that use oral traditions. “Oral traditions form the foundation of Aboriginal societies, connecting speaker and listener in communal experience and uniting past and present in memory.” They are “the means by which knowledge is reproduced, preserved and conveyed from generation to generation” (Hulan & Eigenbrod, in Gaertner, 2016 p.139). In other words accepting testimony, in the form of these Indigenous practices of witnessing, comes with responsibilities. Whether emergent from Indigenous traditions, or in following with Megan Boler’s practice of testimonial reading, these responsibilities are to remember- or a commitment to take forward, teach others and spread the word accepting testimony is not a passive act, nor a one-time event.

The act of accepting testimony between Inuit community members and non-Inuit BW researchers began, in this case, when BearWatch researchers responded to the issues brought up by their Gjoa Haven research partners. By resourcing, planning, and co-designing two workshops with Gjoa Haven HTA representatives to take place in the community, the space was created to engage in the kind of attentive listening that is needed to meaningfully accept testimony. This is the kind of attentive listening that changes you, and connects you to the speaker (Nock, in Gaertner, 2016 p.138). The recording and documenting of the process could be understood as another part of accepting testimony; the commitment to “take forward” and “spread the word”. There are however tensions involved with these latter practices when it comes to the cross-cultural partnership of the BW project. Primarily the fact that these understandings of accepting testimony derive from Indigenous traditions. There are risks and power dynamics at play when western, non-Indigenous researchers take on the responsibility of sharing Indigenous testimonies in academic publications- for academic audiences. Different forms of knowledge outputs, presence of voices, and anticipated “listeners” require different approaches to accepting testimony.

Readers that practice community-based wildlife monitoring in the Canadian Arctic will likely find some familiarities across their own research contexts and the context within which the particularities of Gjoa Haven’s experiences have played out. Other readers, on the other hand, may not have much to gain by conducting a testimonial reading alongside non-Indigenous researchers, and would perhaps prefer to only engage with Gjoa Haven’s testimonies directly. As, such readers are suggested to engage with the following sections to the extent that they resonate with their own positionalities.

Before you continue on your way, you look around in all directions to see whether you are still going into your desired direction. Looking back, you see two tracks. Down the track of cut 1, you can just about (still) see a landmark: Multiple sites of enunciation. Although you can’t really engage with it from here, it reminds you that everyone has different places of beginnings, and therefore might travel this path in multiple directions. Down the cut 3 of track you see opportunities to finally go the field- there is a trip lined up to go to Coral Harbour. Where will you go?

Return to Cut 3 Wayfaring the BW project

4.1 Voices of Thunder Animated Graphic Documentary

"Voices of Thunder" is a community-created, animated graphic documentary, in which Inuit hunters and elders from the community of Gjoa Haven share how they have been impacted by polar bear management policies in their region over the past two decades. This animated graphic documentary resulted from workshops conducted in Gjoa Haven over the summer of 2019. In these workshops, Gjoa Haven hunters, elders and a number of individuals from outside of the community shared their experiences on the impacts of severe polar bear quota reductions, implemented between 2001 and 2015 in the Polar Bear Management Unit of M’Clintock Channel (MC) with each other and with several scientists of the Genome Canada BearWatch project. After these workshops, a narrative script was co-created by the BearWatch scientists, Gjoa Haven HTA representatives and several community members, that brought together interpreted quotes from the workshops, with archival materials and academic publications.

The experiences that are shared in this documentary come from 28 different voices that are narrated as ‘we' in this documentary. The narration of these voices happens through the recorded voice of one speaker from the community, while the archival documentation that provides particularized institutional context is narrated by another speaker from the community. To provide transparency on the multitude that is embedded within this ‘we’, we have added all the community members that contributed to the narrative by name at the end of the video.

Voices of Thunder Inuktitut Syllabics version

Voices of Thunder English version

There seem to be many tracks entangled with this Motion Graphic Documentary. Moving forward, and following the Voices of Thunder, leads you to some of the other research outputs. However, you can also take multiple detours. One brings you to the film’s synopsis and its poster as it was distributed within the film festival circuit. Another allows you take a short-cut to current cusp of emergence, and allows to jump straight to the latest developments around the Voices of Thunder. A third detour set’s you on the track of cut 2: Aesthetic Action, which allows you move alongside the process of film-making within the community. The last option allows you learn more about why this film was made, it will bring you to the beginning of cut 1: voices of Thunder.

Detour to the cusp of emergence

Detour to Cut 2: Aesthetic Action

Detour to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder “Places of Beginning”

Return to Cut 3 Wayfaring the BW project: "Workshops 2019"

3.2 Voices of Thunder Synopsis

"Voices of Thunder" is a community-created, animated graphic documentary, in which Inuit hunters and elders from the community of Gjoa Haven share how they have been impacted by polar bear management policies in their region over the past two decades.

Polar bear management policies in the last two decades, including a polar bear hunting moratorium, have disproportionately impacted Gjoa Haven compared to other Nunavut communities. For two generations they have hardly been able to practice their tradition of hunting polar bears, as a result of international pressures and exclusionary scientific monitoring surveys. Gjoa Haven hunters argue that science could better integrate the knowledge of Inuit themselves and seek recognition for the loss of income, cultural-, and intergenerational knowledge transfer. They want their stories to finally come out - They want their voices of thunder to echo everywhere.

This film was scripted, recorded, drawn and directed by the community members of Gjoa Haven themselves, assisted by a PhD researcher, none of them are professional filmmakers. The video was produced as part of a Genome Canada polar bear research project; BearWatch.

Click here, if you want to return to cut 3 "Workshops summer 2019"

Winds of Change Webpage

This webpage was built, based on the ongoing conversations between BW researchers and the Gjoa Haven HTA. As representatives for the larger community, the board had expressed a desire to have their “voices of thunder echo everywhere”. To help them do so, we built this “Winds of Change” webpage; as an online advocacy tool and reference source for Gjoa Haven’s “Voices of Thunder”. Published in English (below) and Inuktitut, including a Syllabics version, it brings together different material resources that have emerged around the creative collaboration between BW scientists and the Gjoa Haven HTA. Some of these outputs, in particular an interactive timeline, available both in Inuktitut- including a syllabic version- and English, function as a reference source for the Voices of Thunder Animated Graphic Documentary and the community’s appeal for recognition. Other content on the webpage facilitate insights on the culturally embeddedness of Gjoa Haven’s appeals, with the lands and the way in which people keep polar bear related practices alive. Either through sharing memories, stories and extended insights on human/polar bear relationships, or by remembering family histories and great hunters of the past through drumdancing and Pihhiq’s (ancestral songs). The page contains video recordings in which several community members share such memories and stories.

Winds of Change Webpage ENG by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada's BearWatch

Voices of Thunder Interactive slideshow

During the co-production of the animated graphic documentary, it became clear that in addition to an academic publication, webpage and video production, a third way of presenting the experiences as shared by Gjoa Haven’s community members, might be desirable. A document that would provide all the same information, arts and experiences that were shared in the animated graphic documentary- but could also afford for responsive interaction with this content.. A supplemental form of output to the video and webpage, was created in the form of an interactive text-based document, available in three versions; English (below), Inuktitut, and Inuktitut syllabics. It was added to the Winds of Change webpage.

English version slideshow

Voices of Thunder interactive slideshow ENG by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada BearWatch

Inuktitut version slideshow

Voices of Thunder interactive slideshow Inuktitut by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada BearWatch

Inuktitut Syllabics version slideshow

Voices of Thunder interactive slideshow Syllabics by Gjoa Haven HTA and Genome Canada BearWatch

Voices of Thunder testimonial reading

This section invites you to conduct a testimonial reading of Gjoa Haven’s testimonies. The invite consists of a guided reading, in which you as a reader are encouraged to follow alongside non-Indigenous researchers of the Bearwatch project, and: i) Acknowledge initial affective responses towards selected testimonies; ii) Explore how one may be implicated and, if appropriate, how one can respond to to a research legacy that has neglected to properly recognize and engage with Inuit knowledge, and iii) Explore in which ways one can makes oneself accountable to ones relations when conducting such testimonial readings.

This section is explicitly written from the perspective of the academic partners of the BearWatch project, in response to Gjoa Haven’s testimonies, which are in this section presented through selected quotes from the BearWatch workshops, and slides of the co-created “Voices of Thunder” slideshow. Depending on your own positionality, field of expertise, and the particularities of your research collaborations, this invitation may resonate differentially across readers. Readers that practice community-based wildlife monitoring in the Canadian Arctic will likely find some familiarities across their own research contexts and the context within which the particularities of Gjoa Haven’s experiences have played out. Indigenous readers, on the other hand, may not have much to gain by conducting a testimonial reading alongside non-Indigenous researchers, and would perhaps prefer to engage with Gjoa Haven’s testimonies directly. We suggest that as a result of these particularities, readers may want to selectively engage with this section to the degree that is fitting with their positionality.

Affective responses

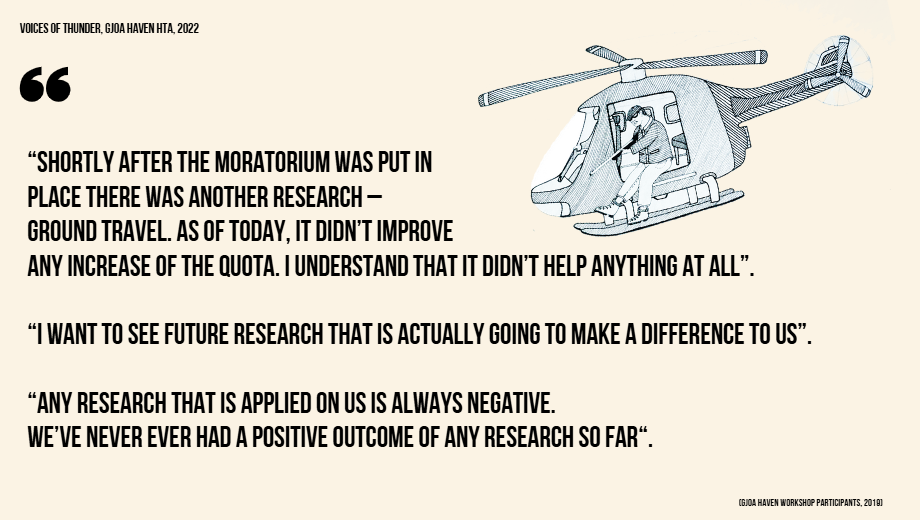

It is not hard to imagine ourselves, as researchers, to be implicated with the experiences shared by community members from Gjoa Haven. The scientific community is in certain cases even directly addressed by workshop participants. Below (figure 6) we share three individual quotes from the larger transcript of the 2019 workshops to provide insight into the ways in which some community members consider scientific research to be entangled with their experiences around quota setting.

These expressed critiques towards the processes and outcomes of research over the past decades, provoked a range of affective reactions among the non-Indigenous researchers of the Bearwatch project. Affect relates here to the emotional and attitudinal engagement with the subject matter, as contrasted with the cognitive domain, which refers to knowledge and intellectual skills related to the material (Seel, 2012). Among such initial affective responses were dissociation, defensiveness, and resistance. V.C. De Groot, for example, being immersed in a relationship with the community of Gjoa Haven to a degree not shared by the other academic members of the collective, took such negative perceptions of research to reflect directly on his personal research history with Gjoa Haven. Initially V.C. de Groot pointed out how he has repeatedly reminded the members of the Gjoa Haven HTA throughout their respective collaborations that expectations of outcomes resulting in an upward revision of quota were not going to be met in the shorter term by their shared work. One of the opportunities that a testimonial reading offers us, is to acknowledge the role of emotions and explore how they reflect the stakes at play when we conceptualize ourselves as implicated subjects. Instead of reacting in more “knee-jerk”, or defensive manners, a testimonial reading redirects one towards exploring responses that may assist in becoming more accountable research partner towards the communities one collaborates with.

De Wildt, Whitelaw and Lougheed did not perceive Gjoa Haven’s critique of research outcomes as directed towards V.C de Groot’s work per se. Rather they saw such comments as expressing frustration with research practices in general, extending beyond projects related to polar bears - and as a critique of the GN, in particular towards their surveys leading to Gjoa Haven’s near moratorium, and their subsequent lack of timely accountability towards the community. The initial affective response from those three academic partners ranged from defensiveness about the legitimacy of scientific research, a fear of losing community support, and guilt or cognitive dissonance between (violent) historical research practices, and on our current research practices and collaboration.

Such initial affective responses are often left unmentioned in academic publications in favour of more cognitive or rational responses. As a result, many academics do not know how to examine and articulate their feelings towards their own work (Daly, 2005). This can perpetuate oppression, as unexamined emotions like guilt, might lead to denial, or defensiveness that prevent us from studying how affective responses influence practices and choices made within research. Guilt forms a trap of one remaining oriented on the past, whereas the assumption of responsibility allows us to be future-oriented by questioning how historical contributions relate to present conditions. Conducting a testimonial reading can assist us in acknowledging the unsettlement that our affective responses clearly speak to. Rather than letting it trap us into passive feelings of guilt, or lure us towards superficial forms of empathy, testimonial readings allow us to acknowledge, and explore such unsettlement more meaningfully- for example through an ethics of responsibility. To transcend passive empathy as non-Indigenous research, in the context of the settler-colonial state, we must explore self-implication, and our potentials for taking reconciliatory action- while also acknowledging our affective responses (including those of guilt and unsettlement), and allow them to assist us in this process, rather than hold us back. What follows is an exploration of what it would entail to respond to the appeal for recognition from Gjoa Haven HTA, by considering ourselves implicated and accountable.

Invitation: Trail off to read about the materialities of vulnerability in such research

Implication

Before we continue to engage with some of the testimonies shared in the workshop, we wish to caution against the conceptualization of reconciliatory allyship in ways that facilitate ‘’moves towards innocence’’ (Tuck and Yang, 2012); the fallacy of imagining there is an easy road to reconciliation leading to superficial actions that alleviate settler guilt, but do nothing to repatriate land, or undo settler power, coloniality or privilege. Reconciliatory allyship shouldn’t be invoked to reinscribe settler virtues, it should be contemplated alongside the concepts of implication, responsibilities to unsettle settler innocence, and to inspire action (Grundy et al., 2019). The form and the possible degree of acting as allies (especially from within institutions rooted in western-based thinking) depends on the complexity of one's entanglement and the privileges one has within the institution and other interlocking socially inherited structures (see Rothberg 2020, p.87).

Although the quota reductions addressed in the workshops were informed by government surveys, in the 1970s and 1990s, far before Bearwatch scientists started their research in Gjoa Haven- we argue that our practices are entangled within the same research apparatus that lead to the quota reductions to which Gjoa Haven’s testimonies speak. Part of conducting a testimonial reading is to consider oneself as implicated within the larger structures ‘that create the climate of obstacles the other must confront’ (Boler, 1997, p. 257). This “climate” is what Karen Barad refers to as the agential ‘apparatus” (Barad, 2007 p.). And what Rothberg understands as emerging from collectives, like for example the academic institute or the settler-state, to which one subscribes and in turn becomes implicated with (Rothberg, 2019). Our BW partnership consists of academic- and government researchers, hunters, community representatives, funding bodies, etc., which are each shaped and affected in different ways by the socio-political legacy of (polar bear) research practices in Gjoa Haven. To assume responsibility as academic research partners for our structural alignments in this environment we must understand our agency extends beyond the BearWatch project, as part of the larger apparatus of scientific monitoring and management of polar bears in Nunavut. This is the same apparatus from which the prior (government) research was conducted, that has led to the quota reductions, in Gjoa Haven.

The findings of the GN survey, conducted from 1997 to 2000, indicated that the MC sub-population had depleted to less than half of its previous population estimate. Recognizing that there was no community consensus on whether polar bear numbers were declining, and if so, whether this was due to over- harvesting, or migration for reasons like for example environmental disturbances or changes in ice, the NWMB proceeded incrementally (NMWB 2000). They first installed a quota of 12 for the MC PBMU in 2000, followed by a moratorium in 2001. They furthermore charged the Department of Sustainable Development to gather additional information during those two years, in order to develop an effective management plan for subsequent years (NMWB 2000). The only subsequent government-led research activity between the 1997-2000 survey and the next scheduled population survey in 2014 was however the publication of a telemetry study (Taylor et al., 2006) and a community consultation on the listing of polar bears as a species of special concern under the Species at Risk Act (SARA; CWS, 2009). Other projects related to polar bears conducted in Gjoa Haven during this period, were collaborations between Gjoa Haven’s HTA and VC de Groot et al. (2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2015), and a collaboration between Gjoa Haven’s HTA and Darren Keith to document polar bear IQ (Keith, 2005). These projects were conducted in (collaboration with) a community that has been seeking recognition for their disagreement around polar bear research and quota distribution since 2000, with an expectation that researchers address this issue. Neither V.C. de Groot’s nor Keith’s (2005) HTA-invited projects, however, had the resources the scope, or mandate to impact polar bear quota.

This speaks to a tangible gap between community priorities and the infrastructure available to those communities to have their priorities sufficiently funded, permitted and researched. Despite significant resources spent on polar bear research by institutions outside the community, see for example Nunavut’s Wildlife Research Trust (NWMB, 2022a; ITK, 2018), the financial, human, social and administrative capacities of community organisations like HTAs are limited, and their role in setting the research agenda is reactive rather than proactive; they can grant or withhold community sanction of wildlife research, but have limited mechanisms to influence terms or conditions under which this research is executed (Gearheard and Shirley, 2009). While community organizations like HTAs provide insights via consulting, handle requests for community sanction of research funding and permitting, and assume important roles within the research itself, (government) researchers and managers have not made themselves sufficiently available for questions of concern to the community itself. Such dynamics have tangible consequences for ongoing and future (research) partnerships, including our own. When it comes to the monitoring of polar bears specifically, it’s sometimes hard for community-members to distinguish between academically-driven research practices and those conducted by the government of Nunavut as part of monitoring for co-management efforts. In some cases this causes distrust for science as a whole -especially when community interests have been neglected in the past (Wong et al., 2017). Earlier in the research project, for example, some community consultations in Gjoa Haven described by BearWatch researchers as being ‘highjacked’ with questions from the HTA on how the results of BW would affect quota.

Researchers of the Bearwatch project were initially hesitant to enter this conversation. Despite the expressed urgency of the community, the topic of quota setting was considered as outside of our sphere of influence, and scope of scientific research objectives. This testimonial reading made it possible to acknowledge this initial neglect and recognize responsibility towards our research partners to listen and engage with their needs and priorities. Following Rothberg, we are not by default guilty of the lack of accountability displayed by previous research partners in Gjoa Haven - but we do carry a responsibility to acknowledge and address the structures and institutes that have made, and continue to make it possible for researchers to avoid accountability and ignore community priorities.

You seem to have located a Wrecksite: Read about the apparatus of Science based conservation

Response-ability

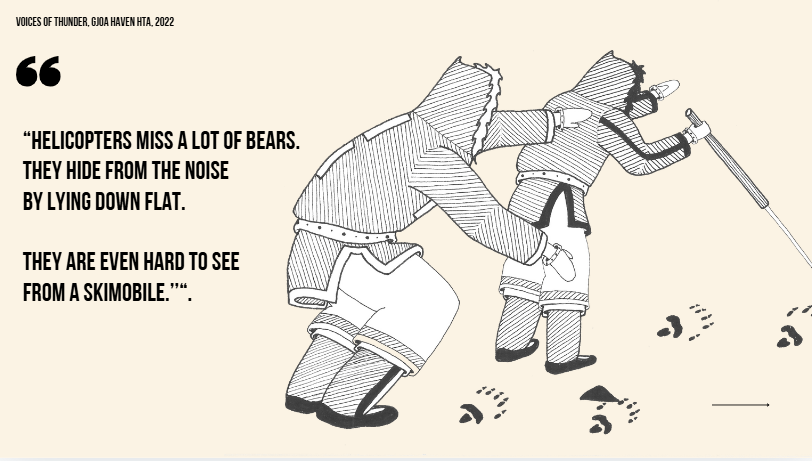

As a result of the variability in the structural alignments researchers may have within their particular research environments, and the expressed interests of the communities one partners with- acting on one’s response-abilities can take different forms. Among the purposes of sharing community experiences around quota reduction impacts, for the Gjoa Haven HTA, lies the need for broader recognition of Inuit knowledge in the form of better integration of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit in polar bear research and management.

The hunters and elders at the workshop and the Gjoa Haven HTA want the ‘inherent value of Inuit knowledge better acknowledged’. They point out that ‘scientific monitoring surveys have limitations, and they want better integration of Inuit knowledge in such research’. Some workshop participants suggested that better integration of their knowledge would be reflected by an increase of quota for McClintock Channel. Responding to such appeals through testimonial reading does not entail validating such claims, or scrutinizing the potential shortcomings of the scientific surveys that have led to the MC PBMU quota reductions- as if they are completely disconnected from our own practices. It rather indicates a possibility to critically explore and take responsibility for our own subscription, and contributions to different agential apparatuses at play when it comes to historical and contemporary recognition of Inuit knowledge in polar bear monitoring research. ‘’One has responsibility always now’’ (Young, 2010, p.108-9).

One of those agential apparatuses, within which the BearWatch project is materially, historically and politically entangled is the field of scientific monitoring and management of polar bears in Nunavut. The meaningful inclusion of Inuit knowledge within these processes, and research related to wildlife co-management continues to be one of the most pressing issues at stake within meaningful Inuit co-management and self-determination (see ITK, 2018). The specific agential, data-driven decisions made by polar bear biologists and research funders, are often made under international pressures to fill data-gaps on Nunavut sub-population abundance. Such decisions usually continue to follow the cut of post-positivist western natural sciences and its understanding of the world through representative data (Brook, 2005; Smylie, 2014). Scientist seeking to make IQ ‘’intelligible’’ within this performance of western natural sciences, either need to break IQ down into such representative data, or place IQ completely outside of the phenomena of Science to become intelligible as ‘another phenomena’ like; values, beliefs, ethics or cultural identities. Neither of those cuts can be considered meaningfully co-constituted with Inuit ways of knowing and being.

In our efforts towards taking responsibility as implicated subjects in this field, we have reflected on how Inuit knowledge was engaged with, to achieve one of the main objectives of the BearWatch project; the optimization of non-invasive community-level polar bear monitoring. We focussed on the project’s engagement with polar bear Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)[1] to inform sample collection activities. To this purpose, BearWatch researchers have collected and analysed TEK through workshops and individual interviews, coupled with participatory mapping. This focus on documenting and compiling TEK, rather than the more complex endeavour of engaging with Inuit Quajimajatuqangit (IQ) [2] as part of a reconciliatory approaches to research, fits within a convention of western science, to selectively incorporate those elements of Inuit knowledge that can be processed and measured as ‘data’ (Agrawal, 2002; Nadasty, 1999). Such ‘data’ is often, as was the case within the Bearwatch project, translated into geographical polygons and markers on a map. Among other goals, such mapping had the objective of guiding future on-the-land field sampling.

Underlying this approach was an assumption that knowledge integration is a “technical problem”.In such technical approaches, knowledge integration is approached as the challenge of integrating two compartmentalised bodies of knowledge consisting of codifiable data, to be solved by applying the most appropriate interface (see Nadady, 1999). Such a view leads to Indigenous knowledge being seen as simply a new form of "data" - to be incorporated into research and existing management bureaucracies. The choices that were made within the project as part of this desire to ‘integrate’ TEK into western-based sciences and the subsequent processes of analysing the gathered knowledge, have led to the disconnection of such TEK from IQ - and has therefore lost the distinguishable characteristics that would make this TEK, “traditionally” Inuit.

This observation is not to discount the insights, observations, and contributions to research that such knowledge can provide for monitoring research. However, as a process of meaningfully engaging with Inuit knowledge on its own terms, beyond a data-driven focus, this narrow focus on TEK falls short. Instead of approaching knowledge conciliation as a question of data, Indigenous knowledge should be considered as an invitation to rethink the basic assumptions, values, and practices underlying contemporary processes of research and polar bear management. Many Indigenous people, for example, share an understanding of knowledge not as simply understanding relationships within Creation, but rather as Creation itself (McGregor 2004). Knowledge is something one does.

Although a testimonial reading, in itself, does not provide a more meaningful approaches to conciliating Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and western-based science in polar bear research, it does help us to make ourselves accountable. Rather that merely expressing sympathy or empathy as passive receivers of Gjoa Haven’s appeals for recognition, it helps us redirect towards a self-scrutinizing gaze that allows us to explore our own practices of engaging with Inuit Knowledge. Not only does this open possibilities to reflect upon and consider different (knowledge) conciliation practices moving forward within the research project and community collaboration. The shift towards implication ourselves, also draws attention to the spaces we inhabit and the conditions that allow for certain affordances for some, and limitations for others. What are for example the implications, and responsibilities that come with our position as witnesses of Gjoa Haven’s testimonies? And what are the implications for readers when witnessing our “witnessing” through this writing. How does it differ from witnessing Gjoa Haven testimonies directly? And how do we hold ourselves accountable in such variable positions?

- ↑ We regard TEK Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) as a derivative of IQ. Its definition originates from Western academia rather than from Aboriginal communities themselves, and can be understood as "the knowledge of Native people about their natural environment" (McGregor, 2008, p. 145).

- ↑ We use the term ‘Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit’ (IQ) to refer to a holistic set of Inuit values, principles and knowledge that guide relationships among Inuit, animals and their environment (Arnakak, 2000 ; Arnakak, 2002 ; Nunavut Department of Education, 2007; Wenzel, 2004).

Relational accountability

We explored such frustrations, above, as expressed by some of the Gjoa Haven community members that participated in the 2019 workshops, by exploring the culturally differentiated forms of accountability as practiced within western sciences, and described by scholars who have written on accountability within Indigenous research paradigms. Many Indigenous cultures construe accountability as relational, personal, collective, and with a focus on process rather than outcomes (Wilson, 2008). Within an Indigenous research paradigm that functions within a relational worldview of collective responsibility, and intra-dependency- accountability is often quite literally understood in terms of recognizing one’s responsibilities and making oneself accountable to ones more-than-human relations (Wilson, 2008; McGregor, 2009; Kovach, 2021).

Traditional understandings of accountability within western academia as the occasional ‘presenting back’ final outcomes of research to partnering communities, come across as distant and disengaged in comparison (reference).

This quote speaks to an expectation, from Gjoa Haven hunters who were present at our workshops, that researchers take responsibility for the social implications of research results that do not translate into preferable outcomes for the communities per se. In the case of Gjoa Haven, many community members expressed feeling like they had to fend for themselves after the considerable cut in polar bear quota. And that the support they were promised, was never delivered.

The social sciences and the humanities have become arenas for critical conversations about the implications of research results on lived-experiences of community partners. However, many natural science researchers consider such an understanding of accountability as outside their skillset, training, and the scope of their research responsibilities. Accountability for outcomes of scientific research is regarded within polar bear research as the responsibility of other organisations within the management environment, for example the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB). Researchers may find, however, that they engage much more effectively with communities when they are aware of a community’s previous experiences with research and their current priorities (Castleden et al. 2012).

Accountability as part of an ethical cross-cultural research process, can’t be an afterthought. Regardless of the scope and methods of our research projects, we should as community-based researchers at the very least make space and listen, to be aware of culturally specific expectations of accountability of the communities we partner with. An awareness of specific previous experiences, needs, and community priorities requires time and long-term sustainable relationships between communities and researchers. Building such a relationship takes time, effort, and funds, resources that are often argued as lying beyond the purview of current research environments or granting programs. This argument is especially relevant in the field of Arctic wildlife monitoring, which is incredibly resource intensive. With limited time in the field and multiple additional responsibilities tied to academic reward structures for tenure-track positions and granting agencies, like the emphasis on production of ‘new knowledge’ and training students, the current academic landscape is not well aligned with Indigenous conceptions of relational accountability (Castleden et al. 2012).

What this writing clarifies is that there are nevertheless ways in which we can make ourselves accountable and conduct responsible research as part of our every day-to-day research practices. Ethical action as part of reconciliatory research, may take the shape of creating space to listen and ask questions about responsibility. Conducting a testimonial reading allows for a form of witnessing, that holds the listener accountable to his or her response. It helps us explore manners in which we can move from passive empathy to a response that actively implicates ourselves and asks how we may contribute to change in the practices and structures of the agential apparatuses of which we are part.

Emergent landmark: Listening and Witnessing

Another point of beginning

This manuscript describes the transformation of what originally would have been an academic representation of Gjoa Haven’s experiences on the impacts of significant quota reductions, but evolved to a co-creative process of accepting testimony between Gjoa Haven community members and academic researchers within the BearWatch partnership. By choosing to engage in ongoing conversations and collaborate on different research outputs we have been able to engage with the desire for recognition as expressed by several Gjoa Haven HTA representatives in different ways. As part of our considerations, we co-created an animated graphic documentary, built a website and chose to use the medium of academic publishing as a platform to question the responsibilities that university-based researchers have towards some of the impacts described by Gjoa Haven’s testimonies as implicated subjects. This choice has not only redirected us away from a damage-centric approach where dominant actors get to passively engage, consume, or grant a hearing to ‘usually suppressed voices’ (Jones and Jenkins, 2008), but also opens a pathway to exploring reconciliatory action based on a premise of responsibility and difference.

The “Voices of Thunder” Animated Graphic Documentary has been screened multiple times in Gjoa Haven. Its final cut was screened first for the HTA in a special meeting, and then as part of a smaller gathering in which community members that either featured, or co-produced the film- to gain final feedback, before the last render. The film was then screened after a sponsored feast for the whole community, as part of a festive opening of our final workshops, in combination with several other short videos that we shot. After these workshops the film was shared in the Gjoa Haven community Facebook page, with the explicit call to share the movie and show it to friends and family within and outside of Gjoa Haven. It was also screened at several academic conferences related to the (Canadian) Arctic and wildlife management. Among them was a plenary screening at the Annual Science Meeting of ArcticNet in Toronto, 2022, and it was screened as an opening movie during Critical Arctic Studies conference in Rovaniemi, 2023. We furthermore circulated the movie in the film festival circuit, where it got accepted and screened at several relevant festivals like; Society for Visual Anthropology Film and Media Festival (SVAFMF) in Toronto, 2023, Aulajut: Nunavut International Film Festival in Iqaluit, 2023, Dawson City International Short Film Festival in Dawson, 2024 and the Available Light Film Festival in Yukon, 2024. Finally, it was taken up in the online collection of imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival in 2023.

The film was not only disseminated by BearWatch researchers. The HTA screened the movie at a regional meeting during which the HTA’s of Gjoa Haven, Taloyoak and Cambridge Bay met with the Kitikmeot Regional Wildlife Board. The film was received with praise from the regional board and the other two communities. A Member of the Legislative Assembly, who resides in Gjoa Haven, leveraged the film, together with the “Winds of Change” website in a letter to the Minister of Environment to call attention to Gjoa Haven testimonies and request ‘a detailed update’ on the ‘department’s work with the Gjoa Haven Hunters and Trappers Association to manage this subpopulation’.

As for this manuscript and the testimonial reading. It is clear that a radical shift of self-understanding by many institution-based (non-Indigenous) researchers in relation to their subject(s) and partnering communities is needed. This manuscript invites its readers to engage with Gjoa Haven appeals in different ways- and leave space to choose those that feel more appropriate to ones positioning towards our subject. We nevertheless hope to inspire our academic audience(s), especially those researching wildlife in Nunavut (and beyond), to recognize themselves as structurally implicated in the context that has contributed to the experiences of which the testimonies in this manuscript speak. The strategies used by the academic partners of BW to move beyond passive empathy, and beyond unhelpful categories like innocence and guilt, towards identifying ways to act in solidarity with their community partners could, we hope, serve as helpful considerations for academic researchers committed to challenging the structural injustices faced by the communities they work with.