Knowledge as Movement and Dwelling: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

This particular one, marks my understanding of how some knowledge only comes into being through movement- or may only exist ''as'' movement. | This particular one, marks my understanding of how some knowledge only comes into being through movement- or may only exist ''as'' movement. | ||

"Becoming nomadic" , the notion of transience and of "passing", as Rosi Braidotti refers to such ways of knowing, binds us to multiple others in a web of complex interrelations, kinship, social bonding and flexible citizenship (Braidotti, 2006). This is not knowledge that can be learnt from a book, nor is it knowledge that can be categorized or transferred for shared understanding outside of its relational events (Ingold, 2022). | "Becoming nomadic" , the notion of transience and of "passing", as Rosi Braidotti refers to such ways of knowing, binds us to multiple others in a web of complex interrelations, kinship, social bonding and flexible citizenship (Braidotti, 2006 p.271). This is not knowledge that can be learnt from a book, nor is it knowledge that can be categorized or transferred for shared understanding outside of its relational events (Ingold, 2022). As Ingold points out, this kind of knowledge references the world, not other books(Ingold, 2013 Making p.15). | ||

My continous moving in-between countries, territories, timezones, languages, cultures, relationships allowed for intra-relational thinking across entities and events, rather than inter-relational thinking merely between entities and events. It started to create tentative opening in which my campervan Butter, the covid-virus, hot tarmac, the seasons, vaccines, all became agents in the production of space, time, meaning and matter within my research, instead of the other way around. Slowly, I started to understand that any knowledge generated outside of the Cartesian cut, requires attunement to the agential forces of all the entities and events of its relational web as you move through and alongside them. | |||

Revision as of 13:39, 26 January 2025

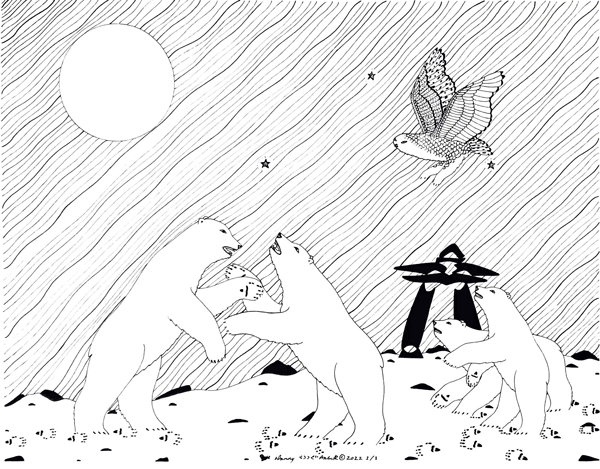

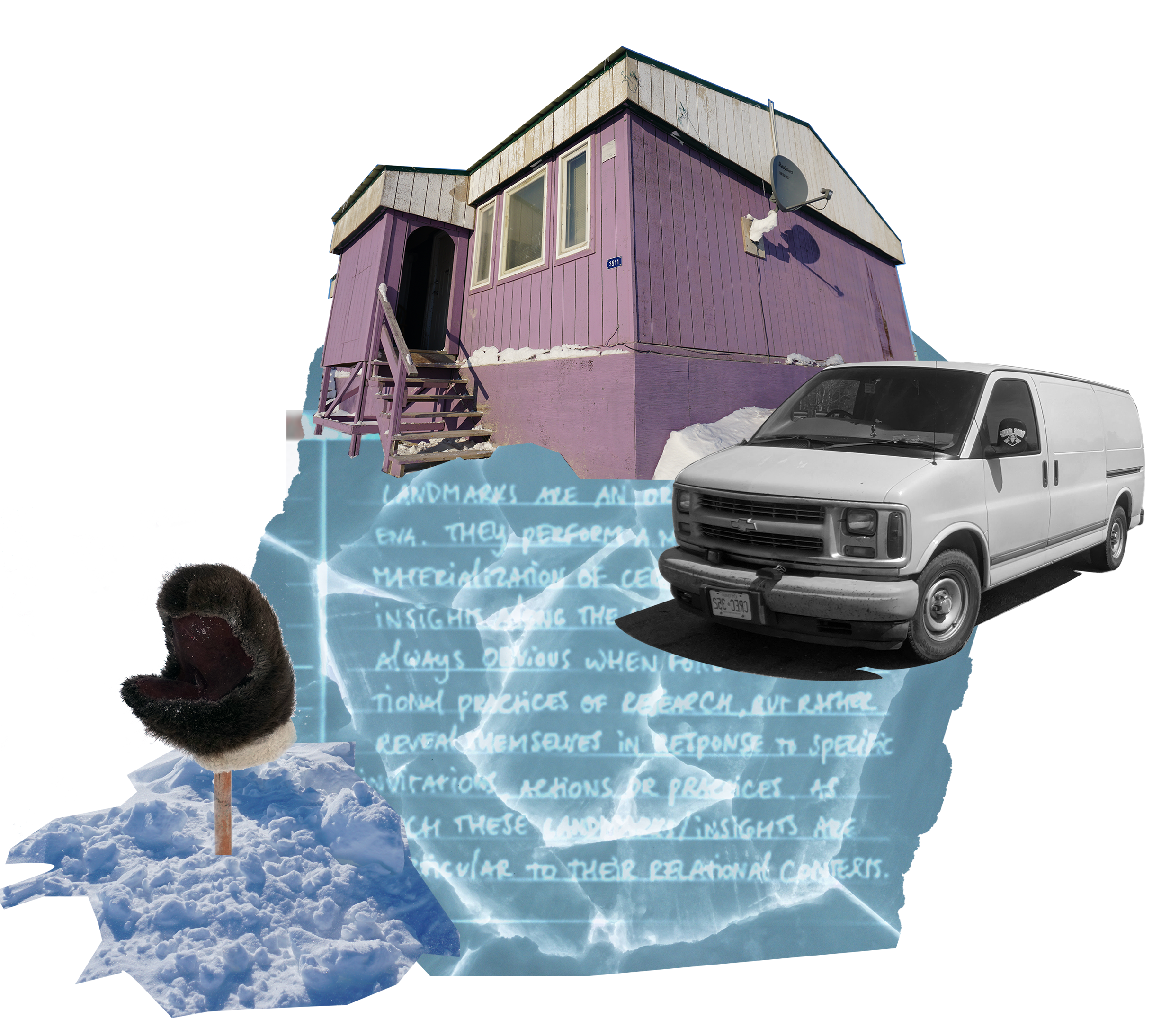

Landmarks are defining features in the land that traditionally play an important role in Inuit topographical understandings of their land and its resources. They are important orienting features to keep one's bearing while travelling and to determine where one is located at any given moment[1].

As a figure in this Knowledge-Land-Scape, "Landmarks" perform the materialization of certain findings and emergent insights along the way.

This particular one, marks my understanding of how some knowledge only comes into being through movement- or may only exist as movement.

"Becoming nomadic" , the notion of transience and of "passing", as Rosi Braidotti refers to such ways of knowing, binds us to multiple others in a web of complex interrelations, kinship, social bonding and flexible citizenship (Braidotti, 2006 p.271). This is not knowledge that can be learnt from a book, nor is it knowledge that can be categorized or transferred for shared understanding outside of its relational events (Ingold, 2022). As Ingold points out, this kind of knowledge references the world, not other books(Ingold, 2013 Making p.15).

My continous moving in-between countries, territories, timezones, languages, cultures, relationships allowed for intra-relational thinking across entities and events, rather than inter-relational thinking merely between entities and events. It started to create tentative opening in which my campervan Butter, the covid-virus, hot tarmac, the seasons, vaccines, all became agents in the production of space, time, meaning and matter within my research, instead of the other way around. Slowly, I started to understand that any knowledge generated outside of the Cartesian cut, requires attunement to the agential forces of all the entities and events of its relational web as you move through and alongside them.

Then return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder, or Cut 3: Wayfaring the Bearwatch project

Cut 3: Wayfaring the BearWatch Project

- ↑ Aporta, C. (2004). Routes, trails and tracks: Trail breaking among the Inuit of Igloolik. Études/Inuit/Studies, 28(2), 9-38.