Knowledge co-production in BearWatch: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The start of my PhD trajectory coincided with a particularly ‘’messy’’ moment in the project- where a change of project partners, -co-funders and -Principle Investigators had required the project to pivot significantly. As a result, many of the research activities that were originally scheduled as part of the social science aspect of the project did not take place as planned. As a consequence of such changes, the project acquired a more natural-science heavy profile than I had anticipated before joining the Bearwatch project. Most of the IQ and TEK that had been collected in the project was part of an informative strategy to determine sampling locations in the field, rather than part of a decisive strategy where Inuit Knowledge is engaged across multiple stages of research decision making. Interviews with elders and hunters had revolved around observations and spatial demarcations under the nominator of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) marked on maps. | |||

Such strategies lead to Indigenous knowledge being seen as simply a new form of "data" - to be incorporated into research and existing management bureaucracies. The choices that were made within the project as part of this desire to ‘integrate’ TEK into western-based sciences and the subsequent processes of analysing the gathered knowledge, have led to the disconnection of such TEK from IQ - and has therefore lost the distinguishable characteristics that would make this TEK, “traditionally” Inuit. | |||

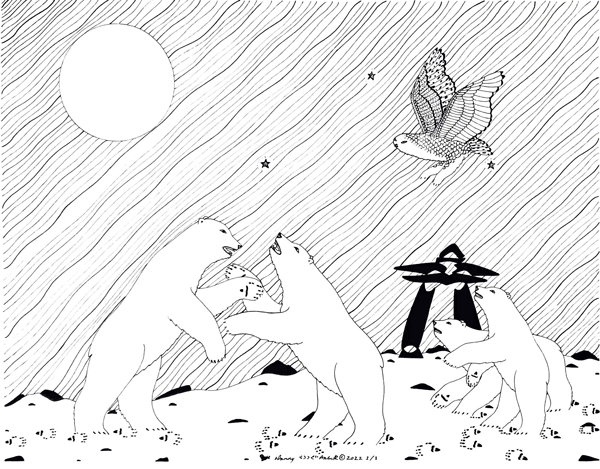

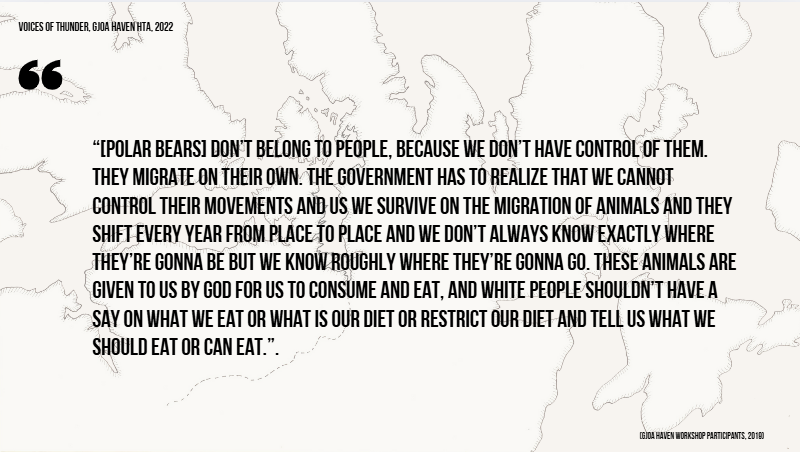

This observation is not to discount the insights, observations, and contributions to research that such knowledge can provide for monitoring research. However, as a process of meaningfully engaging with Inuit knowledge on its own terms, beyond a data-driven focus, this narrow focus on TEK falls short. Instead of approaching knowledge conciliation as a question of data, Indigenous | This observation is not to discount the insights, observations, and contributions to research that such knowledge can provide for monitoring research. However, as a process of meaningfully engaging with Inuit knowledge on its own terms, beyond a data-driven focus, this narrow focus on TEK falls short. Instead of approaching knowledge conciliation as a question of data, Indigenous knowledges should be considered as an invitation to rethink the basic assumptions, values, and practices underlying contemporary processes of research and polar bear management. Many Indigenous people, for example, share an understanding of knowledge not as simply understanding relationships within Creation, but rather as Creation itself (McGregor 2004). Knowledge is something one does. | ||

[[File:Slideshow knowledge is creation.png|border]] | [[File:Slideshow knowledge is creation.png|border]] | ||

One of the ways with which | <span class="next_choice"> One of the ways with which the BearWatch research have started to respond to the challenge of knowledge co-production beyond a data-driven agenda, is by exploring the possibilities of “wayfaring”. If you are curious, you can take a detour to find out more about a small pilot study that we have done. Otherwise, return to our testimonial reading.</span> | ||

<span class="detour link" data-page-title="Another_point_of_beginning_Wayfaring_method" data-section-id="0" data-encounter-type="detour">[[Another point of beginning Wayfaring method|Detour: Different (Knowledge) Conciliation Practices]]</span> | <span class="detour link" data-page-title="Another_point_of_beginning_Wayfaring_method" data-section-id="0" data-encounter-type="detour">[[Another point of beginning Wayfaring method|Detour: Different (Knowledge) Conciliation Practices]]</span> | ||

<span class="return to cut 1 link" data-page-title="Multiple Voices" data-section-id="10" data-encounter-type="return">[[Multiple Voices#Relational Accountability|Return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder]]</span> | <span class="return to cut 1 link" data-page-title="Multiple Voices" data-section-id="10" data-encounter-type="return">[[Multiple Voices#Relational Accountability|Return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder]]</span> | ||

Revision as of 00:49, 14 January 2025

The start of my PhD trajectory coincided with a particularly ‘’messy’’ moment in the project- where a change of project partners, -co-funders and -Principle Investigators had required the project to pivot significantly. As a result, many of the research activities that were originally scheduled as part of the social science aspect of the project did not take place as planned. As a consequence of such changes, the project acquired a more natural-science heavy profile than I had anticipated before joining the Bearwatch project. Most of the IQ and TEK that had been collected in the project was part of an informative strategy to determine sampling locations in the field, rather than part of a decisive strategy where Inuit Knowledge is engaged across multiple stages of research decision making. Interviews with elders and hunters had revolved around observations and spatial demarcations under the nominator of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) marked on maps.

Such strategies lead to Indigenous knowledge being seen as simply a new form of "data" - to be incorporated into research and existing management bureaucracies. The choices that were made within the project as part of this desire to ‘integrate’ TEK into western-based sciences and the subsequent processes of analysing the gathered knowledge, have led to the disconnection of such TEK from IQ - and has therefore lost the distinguishable characteristics that would make this TEK, “traditionally” Inuit.

This observation is not to discount the insights, observations, and contributions to research that such knowledge can provide for monitoring research. However, as a process of meaningfully engaging with Inuit knowledge on its own terms, beyond a data-driven focus, this narrow focus on TEK falls short. Instead of approaching knowledge conciliation as a question of data, Indigenous knowledges should be considered as an invitation to rethink the basic assumptions, values, and practices underlying contemporary processes of research and polar bear management. Many Indigenous people, for example, share an understanding of knowledge not as simply understanding relationships within Creation, but rather as Creation itself (McGregor 2004). Knowledge is something one does.

One of the ways with which the BearWatch research have started to respond to the challenge of knowledge co-production beyond a data-driven agenda, is by exploring the possibilities of “wayfaring”. If you are curious, you can take a detour to find out more about a small pilot study that we have done. Otherwise, return to our testimonial reading.