Science based Conservation: Difference between revisions

Created page with "thumb Scientists committed to the conservation of wildlife in the 1960s were so convinced of the authority of their science as objective and superior to other modes of knowing, that they were blinded to the assimilationist- (Kulchyski and Tester 2007), modernization- (Worster, 1994 ; Loo, 2006) and neo-colonialist ideologies (Campbell, 2004) that tainted their policy recommendations. The sense of urgency leading to signing the 1973 internation..." |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

<span class="next_choice"> </span> | <span class="next_choice"> </span> | ||

<span class="return to cut 1 link" data-page-title=" | <span class="return to cut 1 link" data-page-title=" Multiple Voices" data-section-id="14" data-encounter-type="return">[[Multiple Voices#Response-ability|Cut 1: Voices of Thunder Testimonial Reading]]</span> | ||

Revision as of 00:20, 14 January 2025

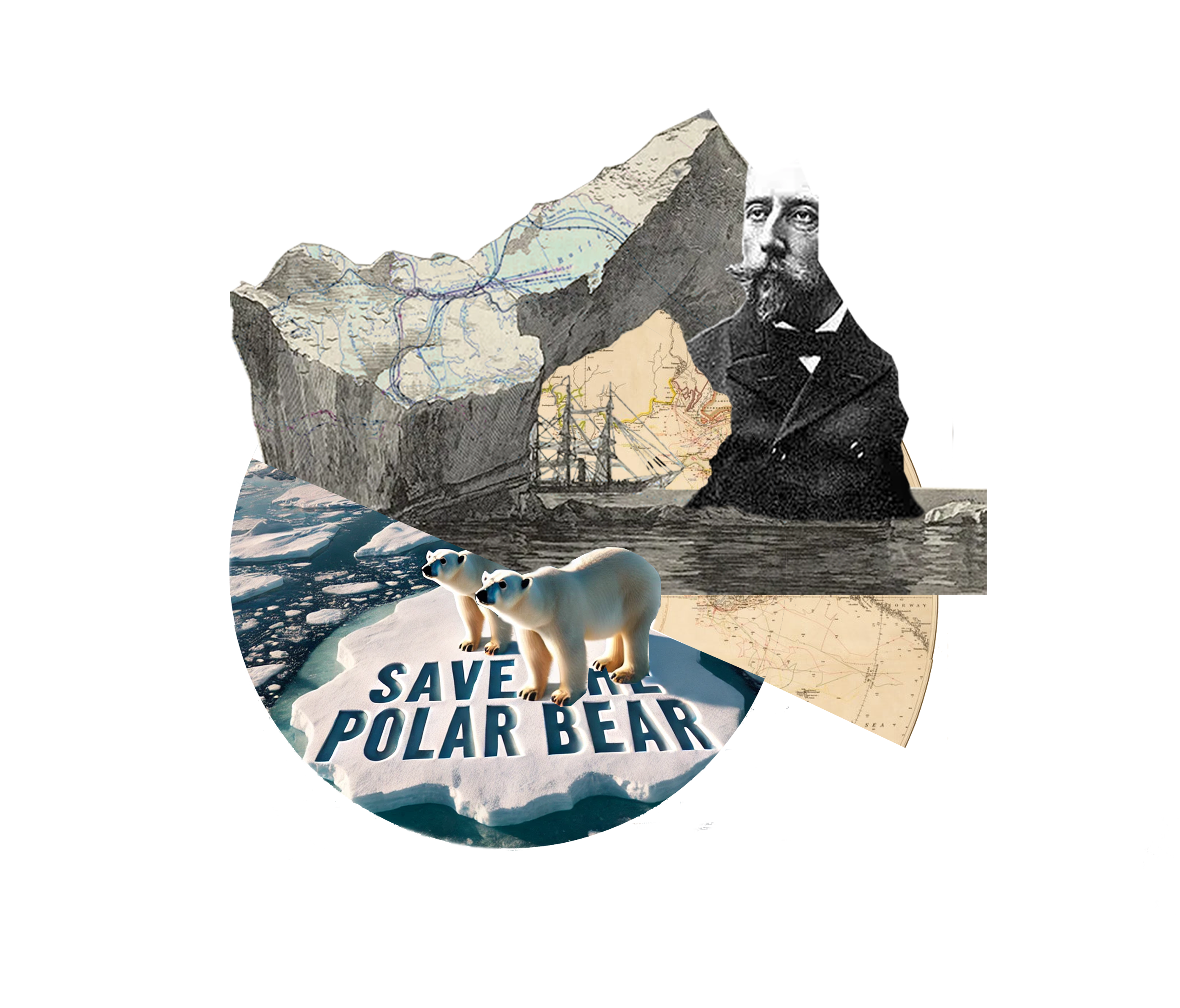

Scientists committed to the conservation of wildlife in the 1960s were so convinced of the authority of their science as objective and superior to other modes of knowing, that they were blinded to the assimilationist- (Kulchyski and Tester 2007), modernization- (Worster, 1994 ; Loo, 2006) and neo-colonialist ideologies (Campbell, 2004) that tainted their policy recommendations. The sense of urgency leading to signing the 1973 international agreement on the conservation of polar bears, was for example based on worries about presumed overhunting of polar bears by Inuit reported in the 1960s (Schweinsburg 1981 in Stirling, 1986), and the lack of overall knowledge on polar bear population dynamics which made it impossible for nation-states to manage harvesting in a way that would ensure ‘intelligent conservation of the resource’ (Fisheries, 1966 p.7).

Relevant here are the notions that the intervention of management-oriented research was considered ‘necessary’ for the species to survive (Jonkel, 1970), and that ‘’intelligent’’ conservation requires representative data, in turn legitimizing the methodological approaches, like tranquilizing polar bears, that wildlife biologists took to gain ‘direct access to nature’ (Schreiber, 2013 p.159). Science's claim to a ‘’truthful’’ account of population numbers, distribution, movement, and evolutionary history of polar bears, of course, presupposed the position of the transcendent researcher as an objective and rational observer. This positioning played, and continues to play, an important part when it comes to the self-legitimization of western-sciences within polar bear co-management and monitoring (See for example Vongraven et al., 2018).

Even if the positivist notions of absolute truth has nowadays in the western natural sciences mostly been replaced by post-positivism, it has retained the exceptionalist positioning of the human -as an outside observer rather than as part of nature. Under post-positivist realism the material world can, in theory, be fully knowable by humans through accurate scientific observation, measurement and prediction.The legitimacy of research within post-positivist disciplines like the natural sciences is determined by how accurately the particular choice and application of scientific methods can be deemed to capture and represent such underlying, material reality of the object under inquiry (Creswell, 2014). Within such a paradigm ‘data’ becomes the widely accepted epistemological unit through which material reality can be reduced to quantifiable bits of information that can be interpreted, described, and represented outside of the context in which it was collected.

Such reductionism stands in stark contrast with many Indigenous cosmologies who consider ‘knowing’ to be entangled with ‘doing’ and as an event that’s inseparable from the complex relations in which the knowledge was produced. Such cosmologies are, due to their lack of subject/object separation, what make Indigenous research paradigms non-representative. Non-representative sciences, which include, but are not limited to Indigenous sciences, are ways of knowing that do not provide for the transcendent perspectives of an external observer- and are therefore resistant to the reductionism of ‘data’, or the urge to claim insights beyond its particular relational context (Ostern et al., 2021). This difference is crucial. When these differences are not taken into account, they can lead to liberal interpretations of ‘data’ as an epistemologically neutral-, and a categorically-inclusive term, that can be stretched to fit multiple knowledge systems. Where it, in fact, materializes critically as an ontologically exclusive category that requires the strict separation between man and nature. A separation which generally does not exist in non-representative Indigenous cosmologies.