Knowledge Co-production: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:The wrecksite.png|thumb]] | [[File:The wrecksite.png|thumb]] | ||

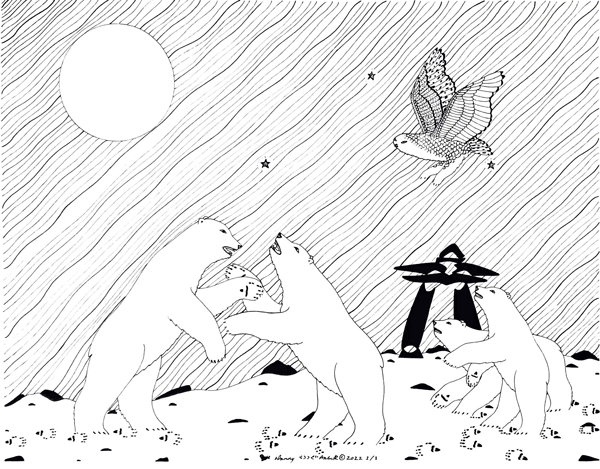

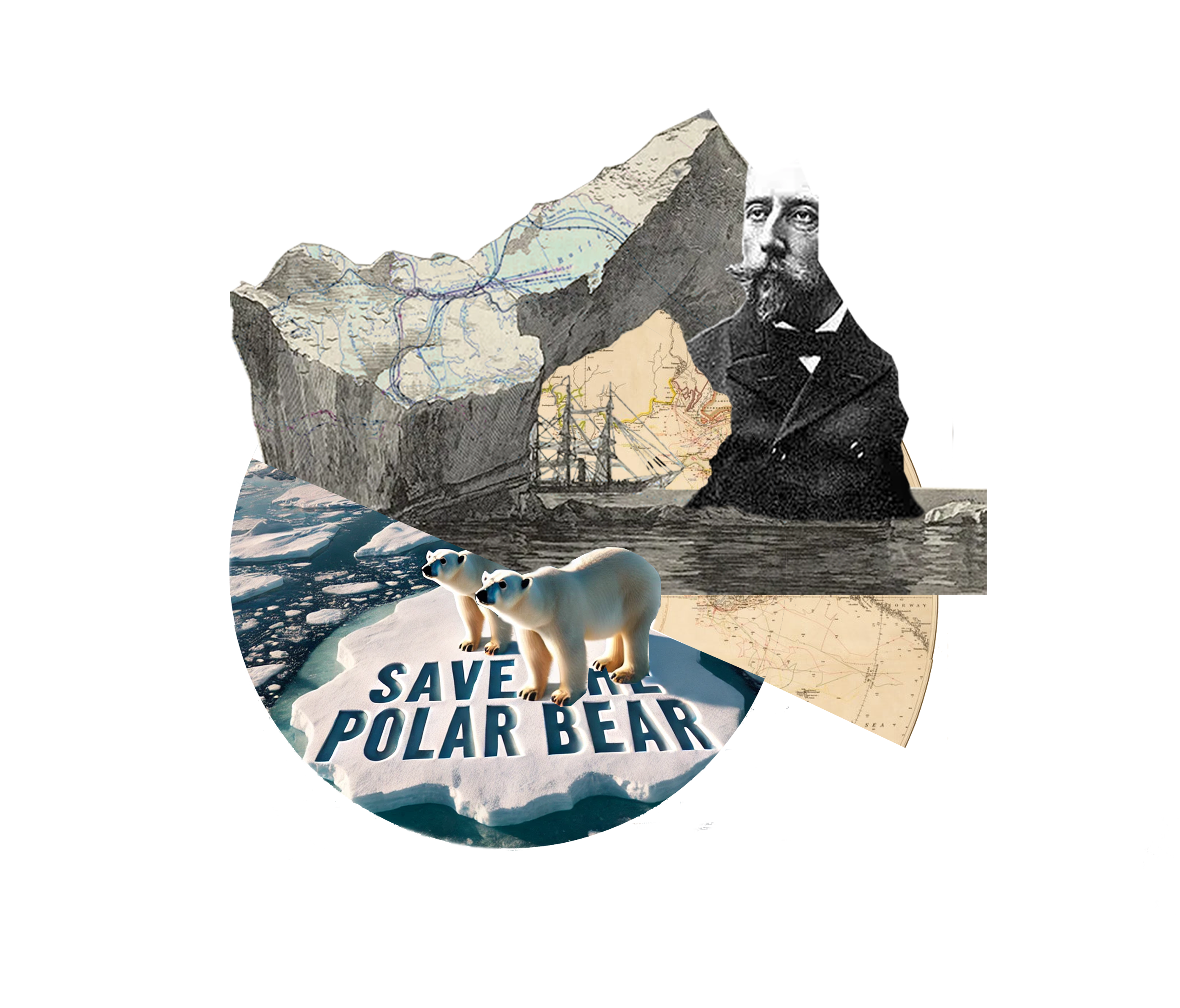

You have found a "Wrecksite". | You have found a "Wrecksite". | ||

This one allows you to think with the im/possibilities of knowledge (co-)production, through the collection of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in polar bear monitoring and co-management. | |||

In scientific wildlife co-management and research the properties of ‘science’ are mostly understood in terms of western natural sciences and as represented through data <ref>Brook, R. (2005). On using expert-based science to “test” local ecological knowledge. Ecology and Society : a Journal of Integrative Science for Resilience and Sustainability., 10(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01478-1002r03</ref><ref>Smylie, J., Olding, M., & Ziegler, C. (2014). Sharing what we know about living a good life: Indigenous approaches to knowledge translation. The Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, 35, 16.</ref>. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) often finds itself related to such sciences, by being reduced to a data set itself - sometimes refered to as TEK. | |||

James Qitsualik, Gjoa Haven HTA vice-chair had the following to say about TEK-interviews conducted as part of polar bear monitoring surveys: | |||

''"A lot of the time they [scientist] already know what they want to know. A lot of the time they just need to know the locations. 'Can you tell me where the den-sites are?"<ref>James Qitsualik, interview, 2022</ref>"'' | |||

That doesn't make TEK interviews essentially useless or unethical. Like "Wrecksites" in this Knowledge-Land-Scape, TEK interviews emerged in our conversation as sites of multiplicity and opportunity. | |||

''"These interviews with the elders are very important, because now, some of them have passed.'' | |||

''"I have also learnt a lot through these [TEK] workshops. I have learnt that Inuit used to hunt polar bears from within their den. It's where they - inexperienced hunters - felt safer. Experienced hunters would hunt them anywhere."<ref>James Qitsualik, interview, 2022</ref>'' | |||

<div class="next_choice"> '''"Return"''' to the BearWatch project. | |||

<small><references /></small> | |||

<span class="return to-cut-3 link" data-page-title="Wayfaring the BearWatch Project" data-section-id=" | <span class="return to-cut-3 link" data-page-title="Wayfaring the BearWatch Project" data-section-id="9" data-encounter-type="return">[[Wayfaring the BearWatch Project#Workshops Summer 2019|Return to Cut 3: Workshops Summer 2019]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:18, 16 August 2025

You have found a "Wrecksite".

This one allows you to think with the im/possibilities of knowledge (co-)production, through the collection of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in polar bear monitoring and co-management.

In scientific wildlife co-management and research the properties of ‘science’ are mostly understood in terms of western natural sciences and as represented through data [1][2]. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) often finds itself related to such sciences, by being reduced to a data set itself - sometimes refered to as TEK.

James Qitsualik, Gjoa Haven HTA vice-chair had the following to say about TEK-interviews conducted as part of polar bear monitoring surveys:

"A lot of the time they [scientist] already know what they want to know. A lot of the time they just need to know the locations. 'Can you tell me where the den-sites are?"[3]"

That doesn't make TEK interviews essentially useless or unethical. Like "Wrecksites" in this Knowledge-Land-Scape, TEK interviews emerged in our conversation as sites of multiplicity and opportunity.

"These interviews with the elders are very important, because now, some of them have passed. "I have also learnt a lot through these [TEK] workshops. I have learnt that Inuit used to hunt polar bears from within their den. It's where they - inexperienced hunters - felt safer. Experienced hunters would hunt them anywhere."[4]

- ↑ Brook, R. (2005). On using expert-based science to “test” local ecological knowledge. Ecology and Society : a Journal of Integrative Science for Resilience and Sustainability., 10(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01478-1002r03

- ↑ Smylie, J., Olding, M., & Ziegler, C. (2014). Sharing what we know about living a good life: Indigenous approaches to knowledge translation. The Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, 35, 16.

- ↑ James Qitsualik, interview, 2022

- ↑ James Qitsualik, interview, 2022