Vulnerability: Difference between revisions

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=Emotional Responses= | |||

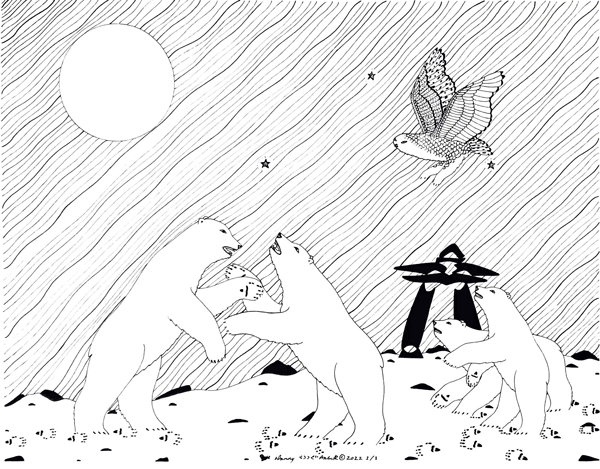

[[File:Invitation background.jpg|thumb]] | |||

One of the opportunities that a testimonial reading offers us is to acknowledge the role of emotions and explore how they reflect the stakes at play when we conceptualize ourselves as implicated subjects. | |||

Our initial responses varied from defensiveness about the legitimacy of scientific research, a fear of losing community support, guilt, and cognitive dissonance between (violent) historical research practices and on our current research collaboration. | |||

One of the BearWatch co-PI's, van Coeverden-de Groot, who has had a collaborative relationship with the community of Gjoa Haven to a degree not shared by the other academic members of the research team, took such negative perceptions of research to reflect directly on his personal research history with Gjoa Haven. | |||

The other researchers, did not perceive Gjoa Haven’s critique of research outcomes as directed towards the defensive PI's prior work in the community per se. Rather they saw such comments as expressing frustration with research practices in general, extending beyond projects related to polar bears - and as a critique of the Government of Nunavut. In particular towards their surveys leading to Gjoa Haven’s near moratorium, and their subsequent lack of timely accountability towards the community. | |||

<span class="pop-up stay-with-the-trouble link" data-page-title=" | |||

<div class="next_choice">Feel free to share your own response on this '''[https://padlet.com/dewildtsaskia/knowledge-land-scape-y0u3ps0t2dxuaskk/ padlet]''' | |||

Keep in mind that the padlet, and your responses are publicly accessible by anyone with the link.</div> | |||

=Vulnerability= | |||

Initial affective responses, as they inevitably happen along the course of research, are often left unmentioned in academic publications in favour of more sanitized, cognitive or rational responses. | |||

Emotions are deemed to stay out of research. As a result, many academics do not know how to examine and articulate their feelings towards their own work<ref>Daly, B. (2005) “Taking Whiteness Personally: Learning to Teach Testimonial Reading and Writing in the College Literature Classroom,” Pedagogy, 5(2), pp. 213–246. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-5-2-213.</ref>. | |||

This can perpetuate oppression, as unexamined emotions like guilt, might lead to denial, or defensiveness that prevent us from studying how affective responses influence practices and choices made within research. Guilt, for example, can form a trap of one remaining oriented on the past<ref>Young, I.M. (2010) Responsibility for Justice. Oxford University Press.</ref>. | |||

<div class="next_choice">Rather than letting it trap us into passive feelings of guilt, or lure us towards superficial forms of empathy, testimonial readings allow us to acknowledge, and explore such unsettlement more meaningfully. However, in doing so, we should beware to not make a move towards innocence. </div> | |||

<small><references /></small> | |||

<span class="pop-up stay-with-the-trouble link" data-page-title="Moves Towards Innocence" data-section-id="0" data-encounter-type="Moves Towards Innocence">[[Moves Towards Innocence|Stay with the trouble: Moves towards innocence]]</span> | |||

Latest revision as of 13:25, 20 July 2025

Emotional Responses[edit]

One of the opportunities that a testimonial reading offers us is to acknowledge the role of emotions and explore how they reflect the stakes at play when we conceptualize ourselves as implicated subjects.

Our initial responses varied from defensiveness about the legitimacy of scientific research, a fear of losing community support, guilt, and cognitive dissonance between (violent) historical research practices and on our current research collaboration.

One of the BearWatch co-PI's, van Coeverden-de Groot, who has had a collaborative relationship with the community of Gjoa Haven to a degree not shared by the other academic members of the research team, took such negative perceptions of research to reflect directly on his personal research history with Gjoa Haven.

The other researchers, did not perceive Gjoa Haven’s critique of research outcomes as directed towards the defensive PI's prior work in the community per se. Rather they saw such comments as expressing frustration with research practices in general, extending beyond projects related to polar bears - and as a critique of the Government of Nunavut. In particular towards their surveys leading to Gjoa Haven’s near moratorium, and their subsequent lack of timely accountability towards the community.

Vulnerability[edit]

Initial affective responses, as they inevitably happen along the course of research, are often left unmentioned in academic publications in favour of more sanitized, cognitive or rational responses.

Emotions are deemed to stay out of research. As a result, many academics do not know how to examine and articulate their feelings towards their own work[1].

This can perpetuate oppression, as unexamined emotions like guilt, might lead to denial, or defensiveness that prevent us from studying how affective responses influence practices and choices made within research. Guilt, for example, can form a trap of one remaining oriented on the past[2].

- ↑ Daly, B. (2005) “Taking Whiteness Personally: Learning to Teach Testimonial Reading and Writing in the College Literature Classroom,” Pedagogy, 5(2), pp. 213–246. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-5-2-213.

- ↑ Young, I.M. (2010) Responsibility for Justice. Oxford University Press.