Science based conservation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:The wrecksite.png|thumb]] | |||

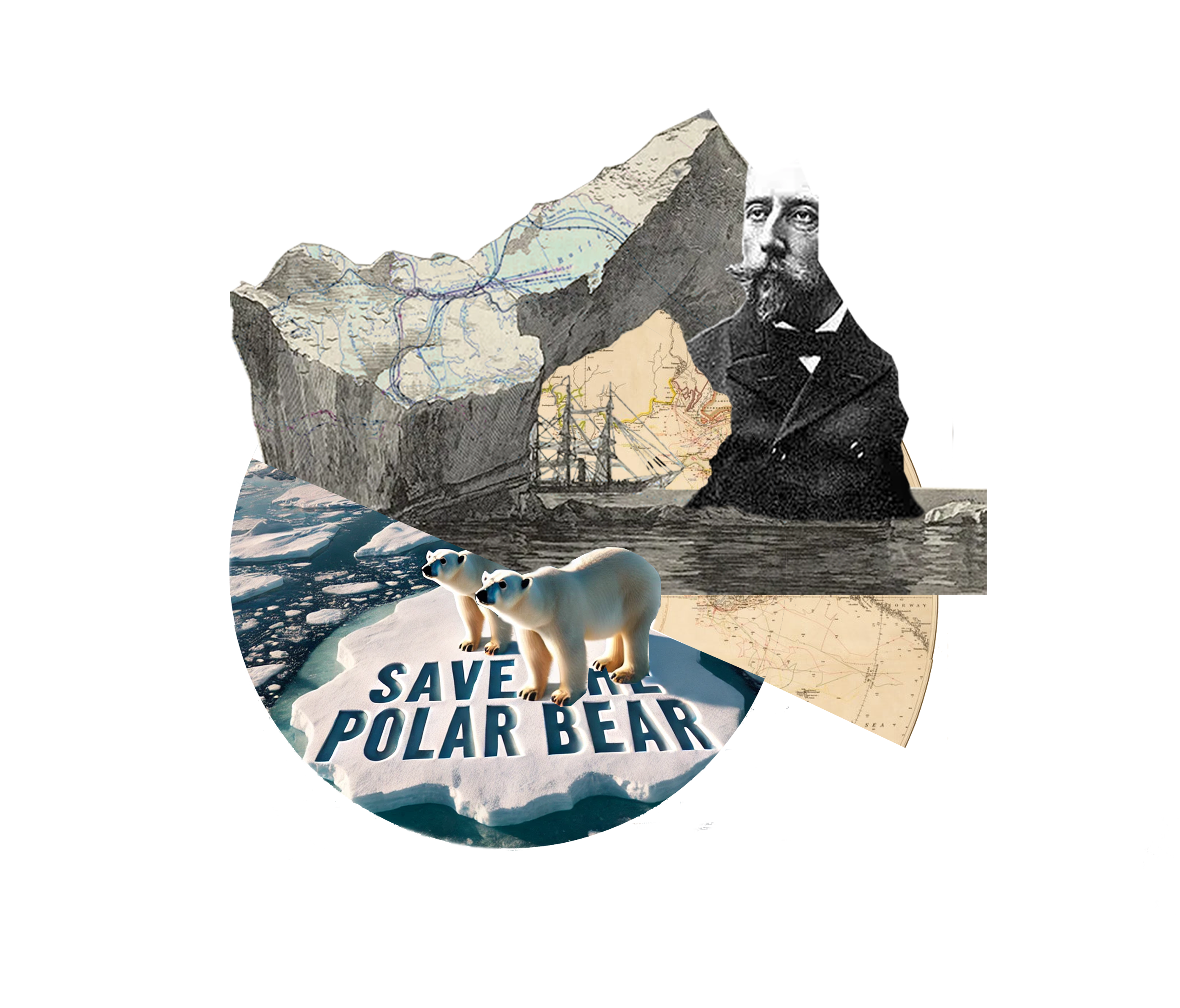

You have found a "Wrecksite". Here and there, "shipwrecks" will manifest themselves. They gesture to the apparatuses that produce conditions under which some phenomena can exists within polar bear monitoring, my research and this knowledge-land-scape- and others cannot. Different shipwrecks gesture to different possibilities and futurities. This one allows you to think with the im/possibilities that western science produces in polar bear conservation. | |||

Such | International polar bear conservation, is conducted ‘in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best available scientific data available’ (Lentfer, 1974). Within such a (western formulated) paradigm ‘data’ becomes the widely accepted epistemological unit through which material reality can be reduced to quantifiable bits of information that can be measured, interpreted, described, and represented. This is the kind of data that the Government of Nunavut collects through their large scale monitoring surveys per Polar Bear Management Unit every 10 years, which then feeds into the polar bear co-management process. Such a reductionist approach to conservation management, dominated by survey data, stands in stark contrast with many Indigenous cosmologies who consider conservation and ‘knowing’ to be inseparable from the complex relations and practices through which the knowledge was produced. Such relational cosmologies are what make Indigenous research paradigms non-representative. Non-representative sciences, which include, but are not limited to Indigenous peoples, are ways of knowing that do not provide for the transcendent perspectives of an external observer that allows for claiming "truth" beyond its particular relational context- and are therefore resistant to the reductionism of ‘data’ (Ostern et al., 2021). | ||

When these differences are not taken into account, they can lead to liberal interpretations of ‘data’ as an epistemologically neutral-, and a categorically-inclusive term, that can be stretched to fit multiple knowledge systems. Instead, the classic concept of data, produced within the apparatus of science-based conservation that dominate government polar bear monitoring efforts, always materializes as an ontologically exclusive category that remains limited to western anthropocentrism. | |||

<div class="next_choice"> After exploring this wrecksite you gained a better understanding of the different ways of knowing that are involved with polar bear conservation, management and monitoring - both internationally and in Nunavut. You suspect that the knowledge people in Gjoa haven might have on polar bears, did not play a significant role in the decisions around the McClintock Channel PBMU moratorium on polar bear hunting when it was set in 2001. | |||

Return to cut 1 and call Gjoa Haven to see what they expect from your contributions if you would center an academic article around their experiences. </span> | |||

<span class="return link" data-page-title=" Voices_of_Thunder " data-section-id=" | <span class="return to cut 1 link" data-page-title=" Voices_of_Thunder " data-section-id="4" data-encounter-type="return">[[Voices of Thunder#Ongoing Conversations|Return to Cut 1: Voices of Thunder]]</span> | ||

Latest revision as of 10:27, 21 January 2025

You have found a "Wrecksite". Here and there, "shipwrecks" will manifest themselves. They gesture to the apparatuses that produce conditions under which some phenomena can exists within polar bear monitoring, my research and this knowledge-land-scape- and others cannot. Different shipwrecks gesture to different possibilities and futurities. This one allows you to think with the im/possibilities that western science produces in polar bear conservation.

International polar bear conservation, is conducted ‘in accordance with sound conservation practices based on the best available scientific data available’ (Lentfer, 1974). Within such a (western formulated) paradigm ‘data’ becomes the widely accepted epistemological unit through which material reality can be reduced to quantifiable bits of information that can be measured, interpreted, described, and represented. This is the kind of data that the Government of Nunavut collects through their large scale monitoring surveys per Polar Bear Management Unit every 10 years, which then feeds into the polar bear co-management process. Such a reductionist approach to conservation management, dominated by survey data, stands in stark contrast with many Indigenous cosmologies who consider conservation and ‘knowing’ to be inseparable from the complex relations and practices through which the knowledge was produced. Such relational cosmologies are what make Indigenous research paradigms non-representative. Non-representative sciences, which include, but are not limited to Indigenous peoples, are ways of knowing that do not provide for the transcendent perspectives of an external observer that allows for claiming "truth" beyond its particular relational context- and are therefore resistant to the reductionism of ‘data’ (Ostern et al., 2021).

When these differences are not taken into account, they can lead to liberal interpretations of ‘data’ as an epistemologically neutral-, and a categorically-inclusive term, that can be stretched to fit multiple knowledge systems. Instead, the classic concept of data, produced within the apparatus of science-based conservation that dominate government polar bear monitoring efforts, always materializes as an ontologically exclusive category that remains limited to western anthropocentrism.

Return to cut 1 and call Gjoa Haven to see what they expect from your contributions if you would center an academic article around their experiences.